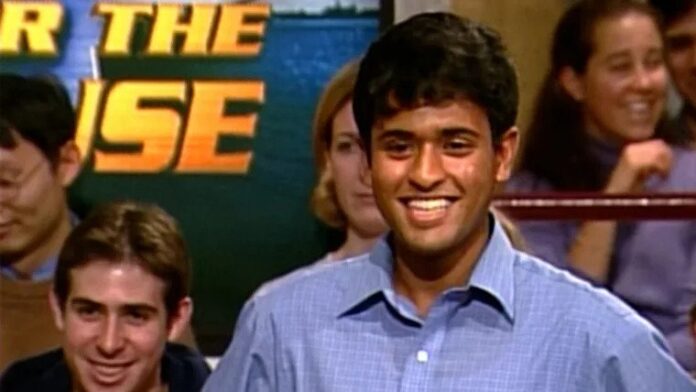

The air is crisp and the atmosphere palpable at the Hampshire Hills Athletic Club in Milford, New Hampshire. On this Saturday morning, attendees shuffle into rows of seats, hopeful for the chance to pose a question to one of the country’s most distinctive presidential candidates. The moderator, USA Today journalist Phillip Bailey, lays out the guidelines for this town hall event and, after a lengthy introduction, he welcomes the grinning Vivek Ramaswamy to the centre of the room.

In February 2023, Ramaswamy, a biotech entrepreneur and self-made millionaire, announced his run for the Republican presidential nomination for the 2024 election. A new entrant to the political realm, the Yale law graduate has made quite the splash in the race for the presidency, garnering much attention from the general media. It might seem rather surprising that the previously unknown Ramaswamy would reach such heights in political discourse, as evident by his reaching of third-place in most primary polling. But combined with his campaign’s vast coffers and evident charisma, Ramaswamy’s criticisms of “wokeness”, polarizing proposals to raise the voting age and suspend aid to Ukraine have made him an attractive target of attention for the news media.

Ramaswamy speaks in elegant prose, a striking confidence, that is clearly salient to potential voters. At the New Hampshire town hall event, his team passes out pamphlets detailing his “ten truths”. Among them, that “human flourishing requires fossil fuels”, and “the nuclear family is the greatest form of governance known to mankind”. Although his audacious statements have garnered an energetic base of followers, he’s simultaneously received plenty of reproval and condemnation, and has turned into a polarizing figure. But, just who is Vivek Ramaswamy?

Background

Born to Indian immigrants in Cincinnati, Ramaswamy was a notable overachiever, graduating as valedictorian from his high school and from Harvard University with a degree in biology. At Harvard, he served as president of the Harvard Political Union, and was notorious as an outspoken defender of libertarianism, and exhibiting a contrarianism that irked his fellow classmates.

An example of this is recounted in an article he wrote for the Harvard Crimson (Harvard’s student newspaper), titled “Uncounted Costs of a Living Wage”. Written in response to the 2005 living wage for janitors campaign initiated by Harvard students and faculty, Ramaswamy embarks on a scorching critique of the movement. If the campaigners were successful, he writes, the wage increase would come at the “cost of respect that the rest of the Harvard community has for these workers”. He believed that the campaign would link the workers’ monetary wages and human dignity, and the “condescending strain of sympathy subtly yet naturally replaces the mutual human respect that otherwise would have existed”. In other words, Ramaswamy believed that the popular campaign to obtain a living wage for Harvard janitors would, paradoxically, lower their own human dignity.

A few years after leaving Harvard, Ramaswamy enrolled at Yale Law School on a scholarship he received from the Paul and Daisy Soros Fellowships for New Americans. Years later, his campaign team would be caught erasing this detail from Ramaswamy’s Wikipedia page, presumably since Paul Soros’ brother, George, was the subject of numerous right-wing conspiracy theories.

Despite a legal education, Ramaswamy turned to the biotechnology sector, where he founded a startup called Roivant. The company’s business model was not to develop drugs themselves, but rather to purchase their patents from larger pharmaceutical companies. Roivant has had a mixed record on drug production, but it has never been profitable.

CSR, DEI, ESG?

Although it was his flagship startup, Roivant isn’t Ramaswamy’s sole business venture. He was upset by the rise of “stakeholder capitalism” which was being promoted by huge companies on the Fortune 500 and enormous asset managers such as Blackrock. In essence, the idea behind stakeholder capitalism is that companies should have more long-term goals than just making a return on investment for shareholders, by considering how something might impact the environment or workers.

Ramaswamy was upset by these developments. In early 2020, he wrote a Wall Street Journal op-ed that bashed stakeholder capitalism. He writes that it is an attempt to remove American democracy’s ability to be the arbiter of moral questions and, instead, give corporate executives a “fundamental role in determining and implementing society’s core values”. Eventually, Ramaswamy wrote a book denouncing the control “wokeness” exerted over the investing framework of corporate shareholders, lamenting the rise of corporate lingo such as “CSR” (corporate social responsibility) and “DEI” (diversity, equity, and inclusion). And at the top was environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing, the lens through which investors evaluated investments by considering the aforementioned factors.

This lead him to found Strive Asset Management, an “anti-woke” asset manager that would “unapologetically prioritize shareholders over other stakeholders”. Although Strive hasn’t surpassed any of the major asset management firms, Ramaswamy’s role in leading the fight against the ESG movement solidified his status among conservatives. Even before announcing his campaign for the presidency, he had made appearances on Tucker Carlson Tonight and was a regular fixture at conservative think-tank functions.

Political Pathways

The 2024 presidential election wasn’t the first time Ramaswamy considered a political career. When Senator Rob Portman (R) retired in 2022, he considered running for his seat in that year’s midterm elections as a Republican.

Ramaswamy’s declaration of his presidential campaign was still sudden, however. Considered a “longshot” by the Associated Press, his formal announcement took place during a Fox News interview in which he lamented that values like “faith, patriotism and hard work” had been replaced with “new secular religions like COVID-ism, climate-ism and gender ideology”.

But how did a candidate that started at zero pull ahead of established congressmen and governors in the crowded GOP primary field?

The answer is simple. Shower the media with endless interviews and television appearances. In one day, he appeared in around 30 interviews and has appeared in more than 150 podcasts since his campaign started. As Politico describes, it’s “the most always-on, always-available strategy of the 2024 presidential race.”

Ramaswamy has pulled a respectable amount of individual donors to his campaign as well. His haul of $5 million in the second quarter of 2023 put him behind only Trump and DeSantis, and ahead of a host of established contenders.

But money and the media aren’t enough to cinch the electoral prize unless your message is compelling to the audience. Just ask Ron DeSantis, whose poll numbers have precipitously declined since he’s announced. But just what is Ramaswamy’s message, though?

The Agenda

The opening Ramaswamy campaign ad starts in a pretty standard fashion – images of a western landscape, a smiling girl holding Old Glory, and a welder hard at work. Then, it makes a sudden and ominous transition to soundless clips of Anthony Fauci, an angry Greta Thunberg, and transgender swimmer Lia Thomas.

These three represent the negative focuses of the Ramaswamy campaign. COVID becomes less and less relevant in the political discourse as time goes on, but the conservative crusade against the size of the federal bureaucracy has since only grown. Ramaswamy believes in rule by executive fiat and has promised to abolish at least five federal agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Department of Education. In addition, he plans to impose eight-year term limits on federal government bureaucrats and repeal Executive Order 11246, which forbids prohibits identity-based discrimination and mandates affirmative action in the federal employment process.

Although Ramaswamy rejects the framing that he is a climate denier, the charge is quite frequently levied against him. And that is not without good reason. At the first Republican primary debate, he boldly asserted that “the climate change agenda is a hoax” and that “more people are dying from climate policies than actual climate change.” When he was involved with Strive, he urged Chevron to drastically increase oil production, and a common catchphrase of his is that America should “drill, frack, burn coal”.

Ramaswamy describes the LGBT rights movement as a “cult” and transgenderism as a “deluded and mentally deranged state”, but he opposes a reversal of marriage equality. Along with candidates Trump and Nikki Haley, Ramaswamy signed a pledge declaring transgender identities illegitimate, and promised to direct federal agencies to commit execute this principle if he were elected.

As for foreign policy, he is conciliatory and less bitter towards the Russian invaders in Ukraine, saying he would end the conflict there by giving major land concessions to Putin and blocking Ukraine’s entry into NATO. Don’t, however, mistake this for pacifism – Ramaswamy proclaims that the U.S. rivalry with China is more dangerous than what it was with the Soviet Union, and calls for total economic decoupling from the P.R.C.

These aren’t even his most controversial policy proposals. Ramaswamy seeks to raise the voting age to 25, disenfranchising an entire chunk of the voting population. Individuals within the 18-25 age range could only vote if they were in the military, served as a first responder, or if they passed the same civics test given to naturalized citizens.

Conclusion

To his credit, Ramaswamy doesn’t obscure or keep his agenda, already hidden. It is loudly and assertively professed, although this may be a feature of trying to appeal to a Republican primary electorate that increasingly searches for the most radical candidates.

Back at the town hall in New Hampshire, Ramaswamy is pressed with a hostile question from a woman at the back of the audience. She attacks him as a political showman and “ruthless capitalist,” complaining that his “spewing [of] nonsensical, fast-talking, empty words interspersed with name-dropping Thomas Jefferson and George Washington should not be misconstrued as knowledgeable”. After being pushed by the moderator to ask a question, the woman finally asks Ramaswamy his thoughts on her monologue.

Ramaswamy is undaunted. He narrows the lengthy statement down to her concern with the qualifications of political newcomers, and clearly addresses why he believes his lack of experience is crucial to get rid of money’s influence in the democratic process.

Perhaps the moment merely shows the usefulness of the New Hampshire primary process in exposing the beliefs and qualities of presidential candidates. Or, maybe illustrates the unabashedness of left-field candidates to express otherwise fringe, sometimes hateful views in the current polarized environment.

Regardless, is undeniable that at the core of the Ramaswamy campaign is a message of visionary ambition. In the campaign ad, he articulates his belief in a new American dream that is fueled by an undying opposition to the “secular religions” he speaks about earlier. He speaks longwindedly about his firm commitment to meritocracy, free speech, and American exceptionalism. “Ask yourself if you believe in these ideals,” he says, “I think most of you do.”