Ambitious, brilliant, and stubborn. These qualities are often used to describe the 6th President of the United States, John Quincy Adams, and his long public service to our country. The son of the wiry old John Adams, one of the nation’s founding fathers, John Quincy Adams was born as a member of America’s “second generation” of political leaders. With the prestigious reputation of his father’s generation to live up to, John Quincy was determined to improve the nation’s domestic infrastructure and the economic well-being of the nation.

These included plans for improved infrastructure such as roads, canals, and bridges. A national academy for the sciences and arts was arranged, as well as a US military academy for the Navy. Adams sought to reduce the nation’s debt, protect the national bank, and reduce taxes on the population whilst raising tariffs on foreign goods to protect US domestic industries.

But John Quincy Adams would only serve one term as president and would be negatively remembered throughout the 19th century. Beset by a staunchly hostile Congress, a lingering political rival, and the stain of the effects of a shady deal, Adams would see little of his dreams reach fruition. Adams’ ambition for progressive government improvements for the national economy was too ahead for the time; yet, his sparks of brilliance and resolute determination make him one of America’s greatest “what if” scenarios.

In the shadow of a giant: John Quincy Adams’ childhood

John Quincy Adams was born on July 11th, 1767, as the second child of John and Abigail Adams. His place of birth was Braintree, Massachusetts. Massachusetts colony, which at that time was ruled by the British Empire. Both John and Abigail Adams were highly educated American colonists, who ensured their son received the highest education available.

John Quincy was a pensive and curious child, who began to write in a diary when he was 12. His first entry, dated November 1st, 1779, says “this morning at 11 o’clock, I took leave of my mamma…” He would write in that diary for the next 68 years.

Though his father, who was an energetic participant in the American Revolution, often was away from home, he kept up an active correspondence with his family through letters. John Adams Sr. wrote letters to his young son instructing him to read ancient Greek and Latin authors such as Virgil, Thucydides, and Hugo Grotius to familiarize himself with literary works on politics, the humanities, science, and history.

Additionally, John Quincy (in his teenage years) would work to translate literary works from Aristotle, Horace, Virgil, and Plato into English. He was successful in these actions, illustrating his immense intellect at such a young age. Furthermore, his translations of ancient literary works would begin his journey of multilingualism, as John Quincy Adams would begin to familiarize himself with Latin and Greek.

During John Quincy’s childhood, he witnessed firsthand the American Revolution. As a child, he gazed upon the fiery blaze that surrounded Bunker Hill and grew up hearing news of the Declaration of Independence and victories against the British at Saratoga and Yorktown.

But by his teenage years, the war was over, and America had ensured its independence through blood and iron. Now as a young adult, John Quincy studied at Harvard University in Boston as a lawyer, graduating second in his class. Regarded as a highly intelligent graduate, John Quincy created his own law practice in 1790 and became financially independent from his parents.

It’s important to understand one key facet of John Quincy Adams’ political life: he had some very big boots to fill. John Adams Sr. had been instrumental in the formulation of the Declaration of Independence; furthermore, he negotiated treaties with Great Britain, the Netherlands, and France to secure American economic ties and prevent the outbreak of war. The dutiful service of John Adams would cement his legacy as one of our nation’s foremost founding fathers. It’s undeniable that John Quincy felt a great deal of pressure to live up to his father, but he managed this burden with prudence and care.

The prestige his father garnered from his political service to the young nation had placed high hopes upon the shoulders of John Quincy, who initially (and wisely) shied away from politics, instead focusing on his law career. But the erudite young attorney published several political essays defending the administration of George Washington – albeit through anonymous means.

Service in the Washington Administration and Romance

John Quincy, owing to the political clout his father possessed and his political support of Washington, was earmarked by the administration for a diplomatic venture to the Netherlands. He initially did not want to go – possibly driven by the fact that his father had spent years abroad, which strained ties with his family – but was convinced by his father.

In London, John Quincy Adams would meet Louisa Catherine Johnson, a daughter of a prominent American merchant. The two would fall in love, and Johnson’s strong temperament and confidence would serve as a beacon of support for Adams. Despite his parent’s objections to the marriage and the lack of a dowry (where the bride’s family would pay the bridegroom as a form of a wedding gift), Adams would continue the marriage. Furthermore, Adams in his diary states he had no qualms about marrying Louisa. It seemed he truly loved his wife, a rare occurrence in the era of arranged marriages and normalized oppression towards women.

“I am a man of reserved, cold, austere, and forbidding manners.” – John Quincy Adams

John Quincy, like his father before him, possessed a stoic, restrained character throughout his life. He was a mediocre public speaker but commanded great respect through his sagacity and steadfast resolution. Adams later in life would recollect “I am a man of reserved, cold, austere, and forbidding manners: my political adversaries say, a gloomy misanthropist, and my personal enemies an unsocial savage.”

Throughout Washington and later through his father’s presidential term, John Quincy would serve as ambassador to Portugal, Prussia, the Netherlands, and Sweden. By this time, John Quincy was fluent in Latin, Greek, French, German, Spanish, Dutch, Italian, and Russian. His calm and intelligent manner allowed him to be an efficient and no-nonsense diplomat, who garnered trade deals and foreign support for the floundering American republic.

Secretary of State

Despite his father’s political rival, Thomas Jefferson, entering office as President in 1800, Adams was still valued by many American politicians for the diplomatic skill he offered the nation. After spending a few years teaching as a professor in Harvard and Brown University, he was appointed minister to Russia. There he quickly befriended Tsar Alexander and established trade agreements with the Russian Empire. In 1811, John Quincy Adams was given an appointment to the Supreme Court of the United States, but he declined, instead preferring to continue his political career.

Adams would help broker a treaty with Great Britain to end the bloody War of 1812. The course of the war, which had seen the White House burned to the ground and defeats in Canada, led Adams to believe that the United States was strong and vibrant but less economically, militarily, and demographically developed compared to other great European powers.

Furthermore, the collapse of the Spanish Empire in Central and South America led to a massive power vacuum in the region, a power vacuum that Adams feared other European colonial powers would exploit.

With these two challenges facing the United States, Adams jumped into the fray as he was appointed Secretary of State under the Monroe administration, a position tasked with maintaining foreign relations with other countries. Adams went to work with a few main doctrines guiding his foreign policy.

First, war with other European powers was to be avoided at all costs, so that the developing US could avoid the devastation of a foreign army marching on its soil. Adams, who had seen firsthand the destruction of the Napoleonic wars upon Europe, desired this same calamitous fate to avoid befalling his own country. Diplomatic interactions with other countries to be as passive and non-threatening as possible, mostly to ensure trade deals and the peaceful acquisition of land through monetary purchases

Second, Central and South America must be protected from European aggression and colonization. President Monroe and John Quincy Adams sought to implement a policy to deter any invasion that might place a powerful European colonial empire next to America’s border. To achieve this, Adams and Monroe created the Monroe Doctrine, a text warning European countries not to interfere in the American continent as it was under their sphere of influence. It was America’s first assertion of its territorial rights to the world and demonstrated the new power the fledgling nation possessed.

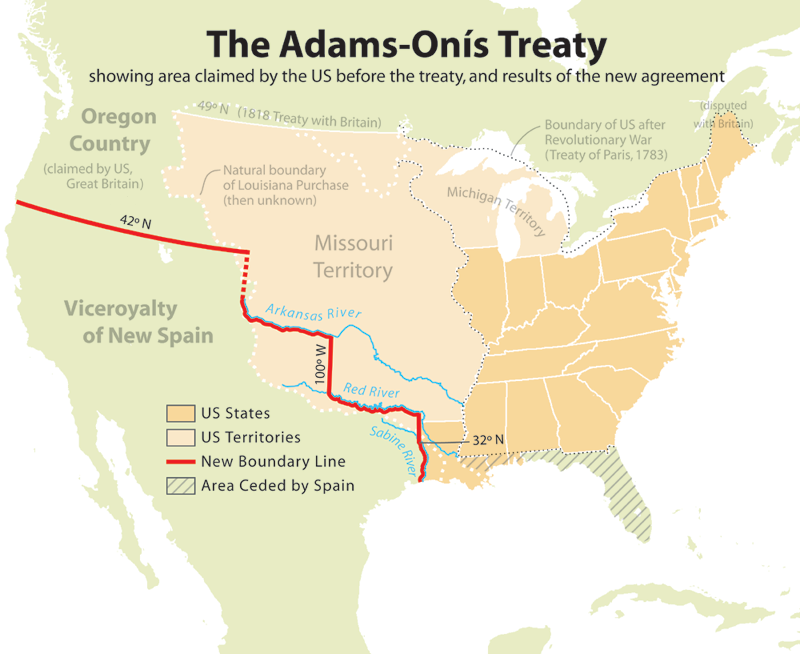

Adam’s 8-year term as Secretary of State would remain unparalleled in American political history. He averted war with Great Britain and France, asserted US hegemony over Central and South America, and garnered territorial concessions from Spain that saw the US annex Florida and set clear boundaries for the US-Spanish (and later Mexican) border. Adams also played a part in the purchase of the Oregon Country (allowing the US access to the Pacific Ocean).

Adams’ superb intellect and foresight allowed him to steadily expand the territorial reach of the United States, whilst avoiding a disastrous war with another main power. “During his eight years as secretary of state, he built a powerful and efficient American diplomatic service,” states Margaret A. Hogan, Managing Editor of the Adams Family Papers. Later biographer James Lewis would recount “He managed to play the cards that he had been dealt.” The National Park Service, on its biographical page of John Quincy Adams, concludes: “[His successes] included equal standing in the family of nations, security within transcontinental boundaries, and sympathy for the national independence and republican aspirations of all the countries of the New World.”

“[Adams’] successes as secretary of state included equal standing in the family of nations, security within transcontinental boundaries, and sympathy for national independence.”

When he was a young child, John Quincy Adams watched the battle unfolding at Bunker Hill. The American Revolution had been won with blood and steel, but the longevity of the nation – and its very survival – also depended upon the ink and pen. The many treaties Adams played a part in formulating laid the foundation for the United States road to becoming an internationally powerful state.

Presidential Election and the Corrupt Bargain

Because of his powerful position as Secretary of State, as well as his massive success throughout the years, John Quincy Adams secured his role as James Monroe’s foremost political successor in the office of the presidency. In 1824, he cast the die and ran for the office of President, with his largest political support residing in New England.

Although his austere nature prevented him from harnessing the same devoted throngs of voters as his more charismatic opponents did, many voters trusted that the experienced and venerated Adams was the right man for the job. However, Adams was also facing the war hero and populist Andrew Jackson, who through his own dashing character had appealed to working-class Americans. Jackson’s nationalistic fervor and martial prowess convinced many Americans, believing in the superiority of their nation above all others, to vote for him.

Furthermore, Adams also had to face off with Henry Clay and William H. Crawford, both of whom were prominent politicians within the Monroe Administration. With the ballot split between four figures, the end result was a virtual tie. Jackson received 99 of the electoral college ballots, Adams 84, Crawford 41, and Clay 37. With no one receiving the majority in the election, the vote went to the House of Representatives. Henry Clay, who was at the time the Speaker of the House, held considerable power over swaying Congress on who to vote for.

Adams met with Clay sometime before the vote. The contents of the meeting are not known specifically, but Adams asked Clay for his support in the congressional vote, with promises that Clay would receive the position of Secretary of State. Clay assented, swaying the vote to Adams and giving him the Presidency. Jackson, despite winning more electoral and popular votes than Adams, had lost. He and his supporters immediately declared that a “Corrupt Bargain” had been struck, and Jackson began his campaign for the presidency of 1828 immediately.

“Adams would win the presidency, but at a fatal cost.”

So why did Adams and Clay, who had run against each other for the presidency cooperate? For starters, Clay deeply respected the experienced Adams and his service to the country. This political experience with policymaking that Adams possessed was contrasted by the relative inexperience of Jackson. Additionally, Clay despised the populist Jackson, whom he regarded as a dangerous demagogue, and feared that the populist would bring unrest to the country.

With this act, Adams won the presidency but at a fatal cost. Jackson would retain the support of much of the South and West working class, and his cause would be inflated by allegations that the corrupt elitists, Adams and Clay, were undemocratically holding power in Washington – leading to the eventual defeat of Adams in the election of 1828.

The Adams Presidency

John Quincy Adams entered office, having won just 1/3 of the popular vote, and with the permanent stain of the Corrupt Bargain upon his character. In the history book The American Pageant, written by David Kennedy and Lizabeth Cohen, professors of history at Harvard and Stanford, they describe the early days of the Adams administration:

“A man of scrupulous honor, Adams entered upon his four-year ‘sentence’ in the White House smarting under charges of ‘bargain,’ ‘corruption,’ and ‘usurpation.’ Fewer than one-third of the voters had voted for him.

“[Adams] would have found it difficult to win popular support even under the most favorable conditions.”

As the first ‘minority president,’ he would have found it difficult to win popular support even under the most favorable conditions. He did not possess many of the usual arts of the politician and scorned those who did. He had achieved high office by commanding respect rather than by courting popularity.”

Despite the scandalous entry into power, Adams got to work as president immediately. He sought to improve the country’s internal infrastructure to develop the nation into a fully-fledged power. Luckily, Adams had arrived in the Oval Office at the same time as one of the most momentous transformations in American society – a transformation that he would strive to take advantage of.

Throughout the 1820s, the industrial revolution, which began in Europe spread to the United States. Although it would be many decades until the US became fully industrialized, the seeds of a new economic and technological age were sown in the early 19th century. Interchangeable parts and the factory system allowed for increased productivity and the compression of labor into smaller spaces. Steam power allowed steamboats to sail upriver, no longer having to rely upon the fickle wind but the monolithic power of coal.

Amidst these new technological advancements, Adams sought to harness the opportunities the nation now possessed. With new advancements in steam power which allowed for easier nautical transportation, Adams dreamed of the construction of canals across the country, to facilitate waterborne travel. This would allow for all corners of the country to be connected, leading to improved trade and commerce. Adams also sought to improve land-based infrastructure, through the creation of paved roads crisscrossing the country, almost like a precursor to the eventual creation of the American highway system.

These improvements in infrastructure align with Clay’s envisioning of the “American System” where the nation would be increasingly interconnected with internal infrastructure, boosting economic prosperity and creating new American industries. Western agricultural products would feed Northern laborers in the factories, who would in turn be processing cotton picked by slave labor in the South.

The American System, if fully implemented, dared to turn the US into a massive power, fully self-sufficient and industrialized. Adams knew that this would be key to the prosperity of his nation – and the ability to defend the young republics of Central and South America from European encroachment.

Additionally, Adams attempted to create a national museum for the sciences, a military naval academy, the adoption of the European Metric system, and monetary reforms. He also sought to reduce the nation’s debt.

However, in the 1820s the nation’s politics were less so revolved around the idea of whether or not a government policy was good, but instead whether a policy was constitutional. The recency of the creation of the constitution led many to become fixated on the powers and limits of the federal government so that there would be an equal balance of state and federal power.

Adams faced significant pushback from all members of the political spectrum. Strict constructionists – those who believed that the government only had powers specifically stated in the constitution – opposed Adams because they believed that the powers to implement internal infrastructure improvements were not in the constitution. Fearful of a strong federal government that might ban slavery, southerners opposed Adams’ ambitious domestic agenda.

“Adams’ four years as president saw little of his enterprising goals fulfilled.”

Most of Adams’ domestic policy agenda items were defeated in Congress, with staunch opposition. Some of his more minor proposals – construction of canals, a national topographical survey by the Army Corps of Engineers, and new railroad lines – passed both houses of Congress. Also, Adams’ managed to reduce the federal deficit from 16 million to 5 million, putting Adams in the rare category of a president who actually reduced, rather than increased, the federal government’s financial debts. But for the most part, Adams’ four years as president saw little of his enterprising goals fulfilled.

A Progressive Policy towards Native Americans

Adams’ domestic agenda inevitably had to deal with the indigenous tribes of North America. The president sought to continue pushing America west, in order to reach the Pacific Coast but was clearly opposed to the outright extermination of Native tribes who stood in his way. He favored a policy of assimilating Native American tribes into white America through peaceful means.

Although this policy would have seen Native American culture and ways of life be destroyed in favor of the industrialized culture of the United States, it was far more progressive than most of the country which sought to expel Native Americans from their land. In fact, nearly 50 years later Eli Parker, a Seneca Indian who served as Commissioner of Indian Affairs under then President Ulysses S. Grant, would advocate for the same policy of assimilation.

![Letter] 1826 Sept. 16, Department of War, [Washington, D.C. to] George M. Troup, Gov[erno]r of Georgia - Digital Library of Georgia](https://dlg.usg.edu/images/iiif/2/dlg%2Fdlg%2Fzlna%2Fdlg_zlna_tcc496%2Fdlg_zlna_tcc496-00001.jp2/0,0,2400,2972/1200,/0/default.jpg)

When Adams learned that the governor of Georgia had forced an unfavorable treaty upon the Muscogee tribe illegally, he declared the treaty null and void. In a new treaty with the Muscogee tribe, Adams allowed them to keep most of their ancestral lands. Although an honorable act, it would cost Adams much support in the deep south, a region that favored the immediate removal of American Indians.

Alongside his more tolerant view on Native Americans, John Quincy Adams additionally was a firm opponent of slavery, viewing it as “a sin before the sight of God.” However, Adams favored the restriction on the expansion of slavery, rather than wholesale abolition. Due to the cause of abolition being in the minority throughout the country in his era, Adams made no effort in his Presidency to attack the wicked institution.

The Election of 1828

Whilst Adams faced failure in Congress, his opponents were stirring a whirlwind of opposition. Andrew Jackson began his campaign for president in the election of 1828 almost immediately after the corrupt bargain had been completed. This marks the first – and only – time in American history that someone has commenced a 4-year election campaign for President.

Adams’ cooperative and experienced cabinet, minor successes in developing America’s economy, and his diplomatic approach to the Native Indian tribes would not save him from the wrath of Jackson. In the midterm elections of 1826, Jacksonian politicians picked up Congressional seats, leading to the first time in American history that Congress was controlled by a rival political party to the President.

In 1828, Jackson’s political party, the Democratic-Republicans, began to adopt innovative campaign techniques to challenge Adams. They utilized pro-Jackson newspapers to publish works arousing public sentiment and encouraging voter turnout. Instead of criticizing Adams’ policies, the Democratic-Republicans instead made the election about the clashing characters of Adams and Jackson. The cold, reserved Adams who was perceived as corrupt was placed next to the charismatic Jackson who, as a frontiersman and settler who was born into the middle class, seemed more relatable to the common man.

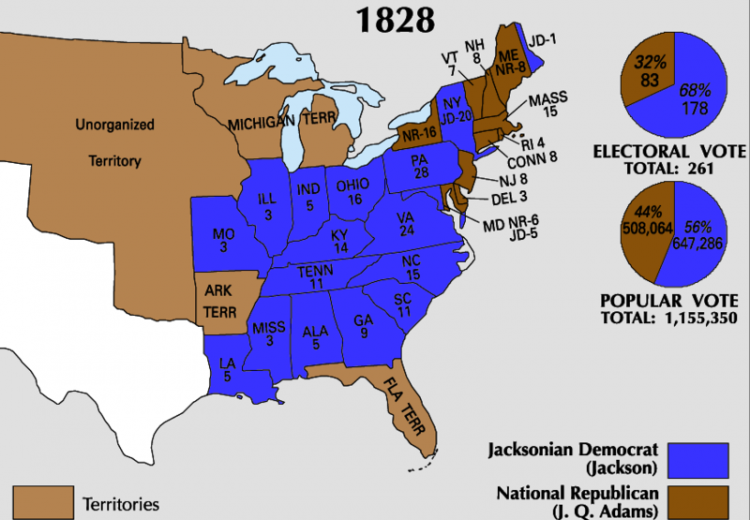

Through all of these factors, Jackson swept the election of 1828 with 178 out of 261 electoral college votes won by himself. Adams, dismayed at the character of Jackson and by the many personal attacks he suffered throughout the campaign, did not attend Jackson’s inauguration as President.

The Tragedy of John Quincy Adams

Adams would serve the rest of his political career as a member of the House of Representatives, representing his home state of Massachusetts. His anti-slavery views led him to oppose the Mexican-American war and the expansion of slavery into the new territories acquired by later administrations.

Whilst giving a speech to Congress, Adams would suffer a cerebral hemorrhage on February 21st, 1848. Carried to a medical room in the Capital building, the former president would spend two days in a sickened state, though still conscious. On February 23rd, John Quincy Adams would die. His last words were “This is the last of Earth. I am content.” Alongside his wife Louisa, a young representative from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln, was also present at his death.

John Quincy Adams remains an enigma amongst American political figures. An immensely successful secretary of state and diplomat, his ambitious agenda as President mostly failed to reach fruition. His plans of massive infrastructure improvement and the fulfillment of the ‘American system’ were stymied by conservative views on the nature of the constitution. If Adams had come along during a later era in history, an era without qualms on the constitutionality of executive action, his plans would likely have been realized, and America probably would have been better off for it.

By many historians’ estimates, Adams was the most intelligent president who ever sat in the Oval Office, with an IQ Rating of 165. His mastery of 8 separate languages clearly sets him apart from most other presidents, and his avaricious appetite for reading instilled in him not only great knowledge but a keen sense of the larger picture. His service as Secretary of State and President was driven by long-term goals to increase his nation’s power and prosperity in a time of vulnerability and internal strife. With such potential, the story of John Quincy Adams remains a tragedy, a story of a man who was too far ahead of his time for his own good.