For every great historical figure in the past, there was someone, whether it be a close companion, lieutenant, or follower, who made their success possible. Although great leaders deservedly warrant praise for their admirable qualities, their success depended on the loyalty of their companions or subordinates.

As a society, our retelling of history mainly concentrates on the big characters of our past, often treating them as solely responsible for their success. But the reality is every great political or military leader, social reformer, and inventor in the fields of science and technology fundamentally relied on help and assistance from others. When analyzing history, it’s important to realize the significance of these followers, the men, and women who loyally helped their leader or friend to achieve that greatness for which they are immortalized.

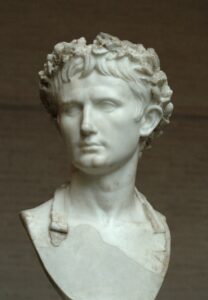

To this day, Caesar Augustus remains one of the most influential men in history. He created the foundational basis for the Roman Empire, a state that would endure for hundreds of years and form the foundation of western civilization. Augustus himself would boast that he “found Rome a city of bricks…and turned it into a city of marble.”

However, Augustus would never have been able to implement the creation of the Roman Empire if not for a dutiful childhood friend, Marcus Agrippa. The relationship between Augustus – the sagacious, calculating leader, and Agrippa – the loyal and quick-thinking follower, provides a case study of the immense valuable followers provide to society. But first, I will discuss the relationship between leadership and followership so we can understand why Agrippa remains such an amazing example of loyalty.

Leadership vs Followership

In today’s culture, leadership – the ability of an individual to guide followers – remains a highly valued and sought-after character trait, for good reason. Just, prudent, and compassionate leaders are key to the functioning of society, from a colossal government to a small school club. Ideal leaders guide and direct the course of action of others, whilst being able to take feedback from others and maintain respect for those following their authority.

Through a variety of cultural norms, society pushes the average person to strive to be a leader. In middle and high Schools across the country, schools create positions of President, Vice President, Treasurer, Secretary, etc.

In the workforce, there are those in leadership positions in departments and committees. Whilst reading scholarly articles published by all manner of research organizations, one can find positions of “senior” researchers, with their prestigious names listed before those of their younger and less experienced colleagues. The status of a “leader” has been historically valued throughout history as well – most of the famous figures we learn about have been those in immense positions of power.

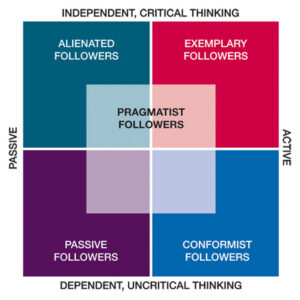

But equally important to the role of a leader are the roles of many of follow them – the official, or unofficial, followers. Followers are those who, well, follow the leader. They are crucial to the success of any group, for without people to follow the leader, all you have is a person talking to air. A word commonly used in academic circles for followers is followership. The Association of the United States Army states: “Followership[is] a reciprocal process of leadership. This term refers to the capacity or willingness to follow within a team or organization.”

An ideal follower is one who remains loyal to follow the goals of one or more leaders, whilst offering feedback to improve the leader’s command and their relationship with subordinates. But the specific qualities that I think reside in the ideal follower, or one who exemplifies followership, are loyalty, intellect, and selflessness. Below, I’ll explain how Agrippa personifies these three valuable character traits.

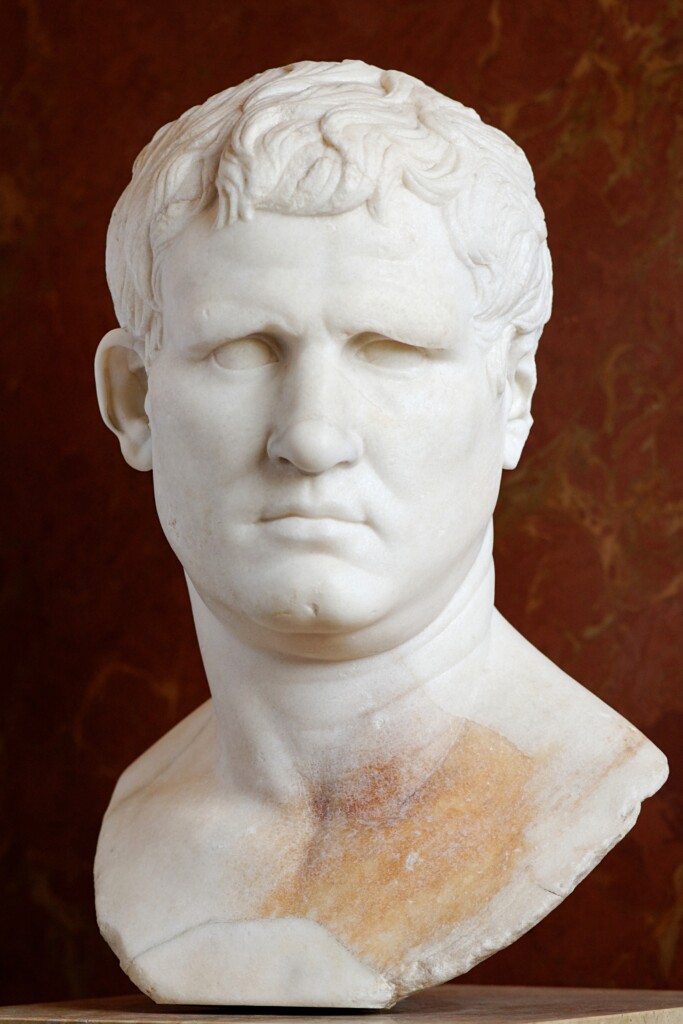

Marcus Agrippa’s Background

Marcus Agrippa was born around 63 B.C. somewhere in northern Italy, to a poor farming family. The name that Marcus would go by in history, Agrippa, was actually a nickname given because he was a breech birth. Marcus would carry the nickname for the rest of his life and it eventually became incorporated into his full name.

In the waning years of the first century B.C, the Roman Republic, which controlled Italy, modern-day France, Spain, and much of North Africa, was embroiled in civil war. The popular Roman general and aristocrat Julius Caesar was fighting for political power against the Roman Senate, the main legislative body of the Republic. By the time of the civil war, Agrippa was in his twenties and quickly found himself on the front lines of Caesar’s civil war.

His loyalty now owed to Julius Caesar, Agrippa befriended a young Gaius Octavius, the nephew of Caesar. Little is known about their early friendship but the two were said to have studied philosophy and science together in Rome and were then dispatched to Greece in order to administer the region.

But in 44 B.C, disaster would strike as Caesar would be slain by assassins in Rome. This left a power vacuum in the eternal city, as factions formed around those loyal to or against Caesar. Octavian and Agrippa were left without their main benefactor, and due to their young age lacked any real political or military power.

However, in a shock to the Roman world, Caesar’s will decreed that Octavian be his heir for all of Caesar’s finances. Octavian was now a symbol of power for pro-Cesareans to rally around, and he moved to Rome with Agrippa to assert his control over the city.

Octavian’s Lieutenant

Agrippa, now friend to the most powerful friend in Rome, was elected tribune of the plebs, a position that held veto power over legislation raised in the Roman Senate. With his political career still in its infancy, Agrippa nevertheless displayed his loyalty to Octavian and was rewarded for that.

Octavian ordered that Agrippa, who was only 20 years old, raise an army of troops in Italy to increase his strength. Agrippa would then lead these troops into Greece, where he would clash with Caesar’s assassins who clashed with Octavian over control with Rome. At the Battle of Philippi, Agrippa would suffer a heavy defeat as his troops were routed by the enemy until reinforcements arrived and saved the day. This affair, with the inexperienced Agrippa being overwhelmed in battle, would be the last time this commander would taste defeat on the battlefield.

By 40 BC, Agrippa had firmly established himself as Octavian’s senior lieutenant. He had never challenged or betrayed his childhood friend, and would continue his service to Octavian in the years to come. One of the greatest things about Octavian and Agrippa’s friendship was that it was extremely complimentary. Octavian was a thinker, a master of political maneuvering, and impatient. He was physically weak and lacked any martial prowess, a flaw that would be exploited by more martial Romans. Agrippa was down-to-earth, blunt, and innovative and would prove himself to be one of the most brilliant generals Rome produced.

Whenever Octavian would fail at a particular task (like commanding an army), Agrippa would take over and save the day. And when their political positions were threatened, Octavian would adeptly muster domestic support by currying favor with Rome’s political elite. However, it was abundantly clear that because of Octavian’s more wealthy background, and his role as Caesar’s heir, he was the senior partner in the relationship. But the nature of their connection is an ideal example of what a leader-follower relationship should look like.

Innovation and Persistence in Sicily

By 40 B.C, the decaying corpse of the Roman Republic was effectively split into three separate domains, ruled by three separate men. Octavian controlled Italy, Spain, and France. Lepidus, a general loyal to Caesar before his assassination, controlled northern Africa. And Mark Antony, Caesar’s senior lieutenant, controlled Greece, Turkey, and Syria. The three men – who were called the Second Triumvirate – divided up Rome between themselves and swore to avoid conflict with each other. But peace was not made to last in the Mediterranean.

In 38 B.C, at the age of 25, Agrippa led campaigns into Gaul, or modern-day France against local Celtic tribes rebelling against Roman Authority. He then crossed the Rhine River, the extreme frontier of the empire, into Germany to defeat hostile tribes that were launching raids into Roman territory.

Agrippa’s young age – just 25 – makes these campaigns notable when considering the fact that the last Roman general to campaign across the Rhine River, Julius Caesar, was 45 years old. It was customary for Roman generals to be well into their 40s when commanding troops; however, the desperate times and Octavian’s desperate need for an able subordinate put the youthful Agrippa onto the battlefield when most other Roman men his age were not yet even independent from their parents.

Little is known about Agrippa’s campaigns, but his troops thought very highly of him and proclaimed him Imperator, or conqueror, and demanded that he be given a triumph, a military parade, in honor of his victories. However, upon returning to Rome, Agrippa discovered that pirates from Sicily (a large island off the coast of Italy) were blockading ports, and launching raids into Roman territory. Because Italy relied on imports of Sicilian and Egyptian grain to survive, Octavian was faced with the threat of starvation, a threat that also translated into danger to his power. Although Agrippa had earned the right to a city-wide celebration in honor of his victories, he refused it to avoid humiliating the troubled Octavian.

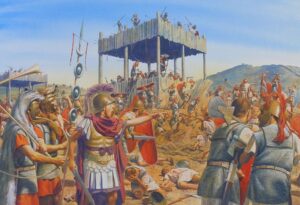

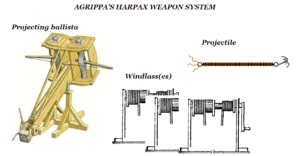

The Sicilian pirates, led by Sextus Pompey, were unmatched in naval combat. Octavian lacked any naval means to face them and put Agrippa on the task of creating a Roman navy from scratch. Attempting to create a training ground for his new fleet, Agrippa dug an artificial canal from Lake Avernus, a massive engineering project. This plan paid off, as the skilled general now had a safe harbor to base his ships. Agrippa led his new fleet against the forces of Sextus Pompey and was initially defeated. But Agrippa persevered, built a new fleet, and invented a new grappling hook, the harpax, to harpoon enemy vessels and sink them.

With these new innovations in place, Agrippa set sail and defeated Sextus Pompey’s pirates twice at sea, allowing Octavian to open up trade routes to allow imports of grain into Italy. For that honor, Agrippa was awarded the corona navalis, a crown made from the wood of captured enemy ships. It would be the first, and only, time that this particular award was given to a Roman military commander. For the young man, who had never commanded naval forces prior to this battle, it was an impressive feat. But greater glory was yet to come for Agrippa.

Agrippa’s Moment of Glory

The Second Triumvirate – the division of Rome into three by Octavian, Lepidus, and Antony – collapsed soon after the war in Sicily. Lepidus’ territory in North Africa was annexed by Octavian, and Antony challenged Octavian’s authority through a series of letters to Rome. Octavian in turn accused Antony of becoming increasingly transfixed by his Egyptian wife Cleopatra, and losing his Roman virtues. The posturing between the two seems to have stemmed from a desire to seize each other’s land and become more powerful in the process.

War finally broke out in 31 B.C, and Agrippa was, yet again, placed in charge of Octavian’s naval forces. Agrippa outmaneuvered Antony’s navy and army in modern-day Greece, eventually defeating them in the Battle of Actium, by utilizing his smaller, lighter ships to overwhelm Antony’s slower and less maneuverable vessels. Antony and Cleopatra lost most of their fleet and army, with the couple eventually committing suicide in Egypt. This decisive victory, earned by the dedication and tactical brilliance of Agrippa, placed Octavian in total control of the Roman Republic.

The triumphant pair would return to Rome, where Octavian awarded him and Agrippa extreme political and judiciary powers. Agrippa set about implementing reforms to the city of Rome’s infrastructure, by rebuilding aqueducts, sewage systems, and public fountains. Agrippa installed fountains throughout the city of Rome so that everyone could walk to a location with clean drinking water.

The general turned-architect also constructed several buildings in Rome, including the Pantheon, a massive complex to commemorate the victory he earned at Actium. He also constructed new bathhouses, so that all Roman citizens could wash freely. Octavian would later boast that “I found Rome a city of bricks, I turned it into a city of marble.” Agrippa certainly had his part in fulfilling that dream.

The Emperor’s Hand in the East

After the conclusion of the civil war, Octavian organized a series of settlements with the Roman Senate that saw the Roman Republic be replaced with a more authoritarian Roman Empire. Octavian was awarded the title of Augustus, or “the majestic” by the Senate. Given supreme political and judicial powers, with control over the administration of the provinces and the armies, Octavian was now an emperor in all but name. It’s at this point that I will call Octavian Augustus, both to reflect his new title and to differentiate him from his past, where he lacked complete control over Rome.

Augustus implemented a series of financial and political reforms in Rome to ensure stability and peace. He fought inflation by increasing the gold value in coinage and standardizing the various coins used throughout the empire. Furthermore, Augustus would, like Agrippa, expand building projects across the empire to improve the quality of roads, aqueducts, and ports. And he additionally settled tens of thousands of military veterans across the empire, not only repaying those who loyally served him in battle but also restoring life into devastated regions of his domain. Thanks to Augustus’ work, Rome began its period of renewed economic stability, named the Pax Romana, or Roman Peace, by historians.

Amidst these reforms and new prosperity, Agrippa was ordered to administer the wealthy eastern provinces in the Middle East. He took over control of the Crimean Peninsula, brokered peace with the Parthians (a hostile people that controlled modern-day Iran), and was regarded as being an extremely equitable administrator. The Jewish populations in the east, so often persecuted and abused by powers in the region, viewed Agrippa in a positive manner.

Augustus, fearful that his own death would lead to a power struggle, heaped upon Agrippa new titles and responsibilities. By 18 B.C, Agrippa’s powers rivaled that of Augustus, although it was clear to all that the latter was the senior partner. Agrippa was undoubtedly now the second most powerful man in Rome, with Augustus even naming Agrippa as his heir.

Agrippa, now more weathered in years, campaigned in Spain and in the Balkans, conquering new territory for the empire in a series of cautious and deliberate campaigns. At the age of 51, whilst campaigning in modern-day Slovenia, Agrippa suddenly died. His body was taken to Rome, where Augustus organized an extravagant funeral for his deceased friend. Augustus would personally bury Agrippa in his own tomb, a final act of affection to his lifelong friend.

Agrippa’s Legacy

"Without Agrippa, Octavian would never have become Emperor."

Agrippa earned eternal fame in Roman history, beloved by the people for his infrastructure improvements and fair administration, admired by the army for his martial prowess, and respected by Augustus for his loyal friendship. As the historian Glen Bowersock states:

“Agrippa deserved the honors Augustus heaped upon him. It is conceivable that without Agrippa, Octavian would never have become emperor. Rome would remember Agrippa for his generosity in attending to aqueducts, sewers, and baths.”

Not only did Agrippa serve as a dutiful subordinate to Augustus, but he also acted as a close friend to the thoughtful ruler. Agrippa had known Augustus since childhood, and both men never betrayed each other, each gifting the other with their loyalty and material rewards. The balanced nature of their relationship, with either man compensating for the other’s failures, ensured that they would soon rule the Mediterranean.

Whenever Augustus deputized Agrippa to oversee operations that Augustus was unable to do, the latter always achieved success through his own determination, adaptability, and sheer intellect. Agrippa personifies loyalty, the defining trait of the ideal follower, and serves as an example of what the ideal follower should look like. It is true that the world needs leaders to inspire change in the world. But we also desperately need followers to see these plans through, so that every future Augustus can have a loyal Agrippa by their side.