The 2020s have been generally described as volatile and unpredictable, leading many to compare it to previous decades. This decade bears the inexorable political violence and cultural convulsions rampant in education, workplaces, and on the streets like in the 1960s. This decade also bears energy shocks and inflation similar to those of the 1970s. This decade even bears the COVID-19 recession’s similar impacts on oil and food prices, banks, the automobile industry, and more, similar to the Great Recession from 2007-09.

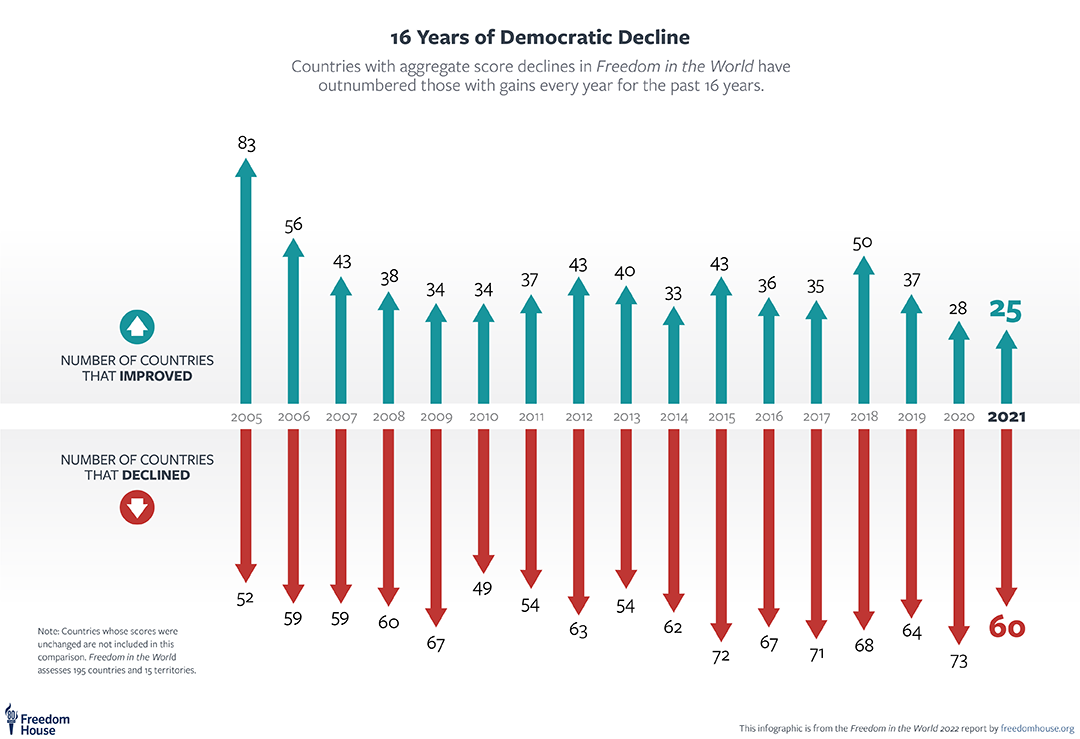

I will be discussing the US’s geopolitical challenges against three foreign powers: China, Russia, and Iran. One can conclude that the 2020s are similar to the 1930s, a period when authoritarianism is rapidly becoming popular in numerous countries. However, the three countries’ authoritarian governance styles are different from those of the 1930s, as the current ones pragmatically use the global economy and capitalist elements to augment their geopolitical power.

As the COVID pandemic subsides, the US’s geopolitical rivalries with the three powers have become more apparent through Russia’s War in Ukraine and efforts to reduce NATO’s influence, China’s menacing of Taiwan and the forging of economic ties with the Global South (developing economies), and Iran’s use of proxy nations and organizations to destabilize the American order in the Middle East. The three adversaries’ growing cooperation undermines America’s political and economic ties with foreign countries. Furthermore, it is not just America’s global standing at stake, but also democracy and freedom threatened by authoritarianism’s looming rise.

Now, it is time to discuss China, the first of the three foreign adversaries of the United States. Throughout the Cold War, China was viewed as an average third-world backwater. Overcoming numerous obstacles, China is now recognized as a leading superpower.

China

Economic Escalation

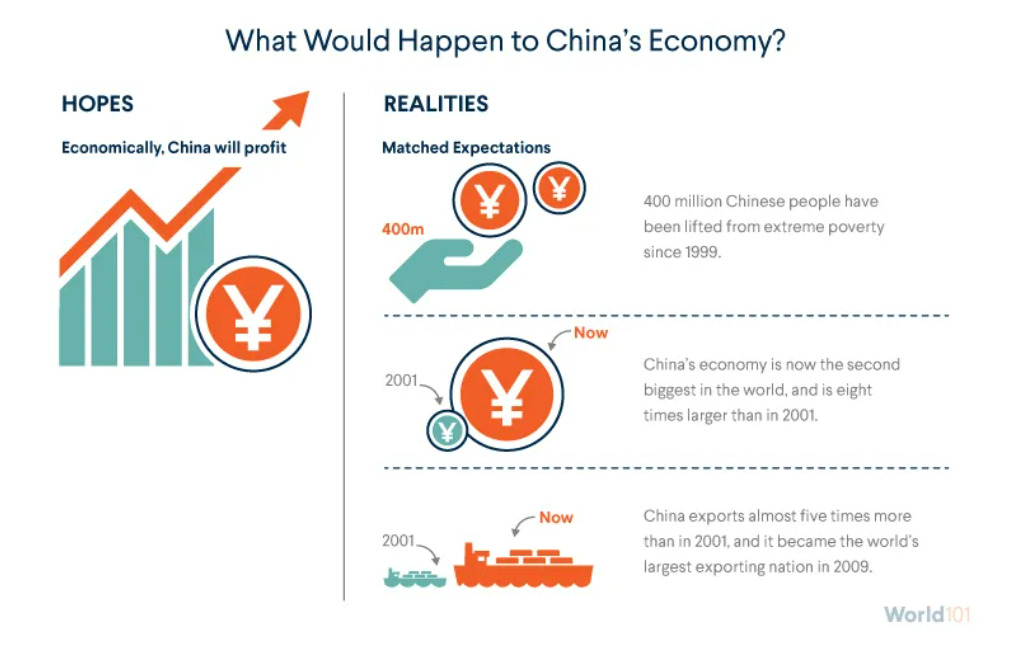

By 1978, under President Deng Xiaoping, China decided to open up its economy by allowing foreign investment, more power for rural farmers’ control over their land, and promising companies low-cost manufacturing. In 2001, China was invited to join the WTO, allowing Beijing to access new trading partners like the United States. As a result, since its membership, China’s economy is eleven times larger than it was in 2001, as trade with the US increased by $448 billion from 1999 to 2019.

Since 2001, the US has initiated 23 cases against China for discriminating against foreign suppliers and goods (e.g. foreign automakers’ forced purchase of Chinese components), providing illegal state subsidies, and controlling supply chains (e.g. taxes and quotas). In addition, US officials have accused Chinese companies of forced technology transfer, a process occurring through joint-venture partnerships. Specifically, this occurs when China requires foreign companies to partner with their firms under WTO rules, which sometimes require the foreign companies to share technological secrets. These secrets eventually make their way to the Chinese government. Deciding to not conform to the Western world order, China is gradually navigating the global economy to work it to its advantage.

Belt & Road Initiative

In 2013, China launched a massive, multi-pronged project: the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI). China’s President Xi’s vision of the BRI includes a network of transportation stretching from China to the former Soviet republics and Southeast Asia, which connects by both land and sea to Africa and Europe. Furthermore, the Chinese have established hundreds of economic zones to create jobs and offer technology (e.g. Huawei’s 5G network) for countries supporting the BRI.

In addition, China is seeking to secure long-term energy supplies from Central Asia and the Middle East, making it more difficult for the US to oversee.

Finally, China’s securing of favors from BRI countries allows Beijing to reinforce leverage over their partners’ policies (e.g. support for the One-China Policy). By pouring investment into the Global South, China’s ulterior geopolitical motives spark harsh criticism. Many countries conclude that China is simply using debt traps to garner support, while others criticize China’s violation of its commitment to climate change (e.g. 2021 – 50% of BRI spending = nonrenewable energy investment).

In an interview with the Financial Times, Yunnan Chen, a Research Fellow at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), analyzes that China is “bailing out its own banks” with the money “paying China’s policy banks or commercial banks,” indicating that China eventually benefits from BRI.

Why is this America’s problem? By appealing to the Global South, China is seeking to expand its geopolitical influence in an attempt to not only gain strategic allies but also erode the US-led, Western global order. Furthermore, as it seeks to erode US influence in the global economy, China’s ambition can be simply inferred: reshape the international order in the long run to its benefit.

Path to Political Prowess

Starting in the 1970s, the US switched diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China (Taiwan) to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In 1971, the UN General Assembly recognized that the PRC is the only legitimate representative of China and removed the ROC from the UN. Viewing China’s growing animosity towards the Soviet Union and economic reform efforts, the US signed the Shanghai Communique in 1972, allowing both countries to discuss geopolitical issues like Taiwan. In 1979, the US officially recognized China, while maintaining the One-China Policy and severing ties with Taiwan. However, Congress passed the Taiwan Relations Act, allowing the US to maintain cultural and commercial ties with Taiwan and requiring the US to support Taiwan’s military. Five years later, the Reagan administration allowed China to purchase American military equipment.

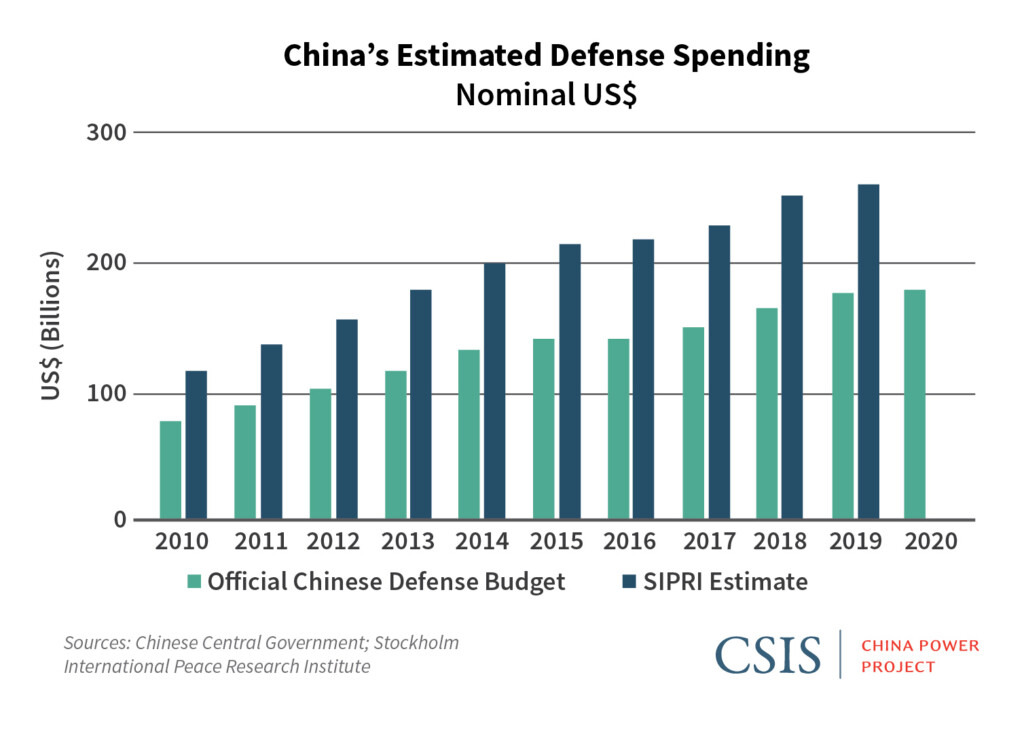

In addition to its growing diplomatic influence, China has invested in expanding its military capabilities. From 2000 to 2016, China’s military budget has increased by 10% each year. By 2022, China’s military budget was $230 billion, only behind the United States. The reasons for China’s military buildup are fairly simple. Beijing desires to provide for its own security like Washington, compensate for its unfavorable geographic position (surrounded by US allies in SE and East Asia), and secure widespread support from citizens and the bureaucracy alike. This rapid expansion of the military budget is part of President Xi’s pledge for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to become a “world-class military” by 2035.

By building a “world-class military,” President Xi has been accelerating China’s nuclear arsenal. As of May 2023, China reached 500 operational nuclear warheads. However, by 2035, the Pentagon estimates that China will reach 1500 nuclear warheads. China’s ambition to expand its nuclear arsenal signals the superpower’s need to deter the US, as the Beijing-Washington relations continue to deteriorate. During the Cold War, China constructed several hundred nuclear weapons to adequately deter other powers like the US and the Soviet Union. However, in light of tense relations with the US, China intends to enhance its military capabilities and become a nuclear superpower.

In addition, to complement its nuclear capabilities, China has been constructing hypersonic missiles. A hypersonic missile travels five times faster than the speed of sound (4000 mph). Unlike a normal ballistic missile, a hypersonic missile can change course maneuver across various terrain, and carry a nuclear warhead. For instance, China’s DF 26 can travel 2500 miles and reenter the atmosphere after exiting ten times faster than the speed of sound. In March 2023, the US Defense Intelligence Agency announced that China is significantly surpassing the US in terms of hypersonic weapons development, stressing the need for reorienting US military priorities.

Taiwan

Complementing its military growth, China has been intensifying its diplomatic strangle of Taiwan. According to the CSIS, China possesses a two-track diplomatic approach to increase pressure on Taipei and soften its own approach. After Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen visited the US and met with Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy, Beijing invited former Taiwan president Ma Ying-jeou. This was Beijing’s attempt to show its willingness to engage in discourse with Ma and the KMT party he previously led. The reason for China’s preference for the KMT is because of the party’s attempt to bind Taiwan closer to China. On the contrary, Taiwan’s ruling party, the DPP, have always favored formal Taiwanese independence.

Furthermore, to increase political pressure on Taiwan, China has been converting many of Taiwan’s supporters to its cause. For instance, capitalizing on moments when Taiwan is under the Democratic Progressive Party’s leadership, China has converted 18 nations to turn their backs on Taiwan by offering money to forge diplomatic relations and economic partnerships.

Moreover, China has initiated several actions against Taiwan, such as sanctions against think tanks, punitive arrests of pro-Taiwan advocates, and disinformation to discredit President Tsai.

Finally, intensifying their exercises after COVID-19, the Chinese military has conducted numerous live-fire drills near Taiwan’s islands and coasts. However, in 2023, Beijing decided to refuse to disclose exercise coordinates to prevent external influence, especially from the US.

South China Sea

In order to project its military power, China designated a critical focal point: the South China Sea. The South China Sea consists of numerous shipping lanes, constituting 21% of global shipping by 2016. Generally, oil and minerals travel north, and food and manufactured goods travel south.

“Political power without economic power is sterile.” – Louis Kelso, economist

China’s effort to fulfill Kelso’s adage becomes manifested through their nine-dash line, a cartographic boundary suggesting that China owns the South China Sea in its entirety. According to the US Department of Defense, China has installed intelligence equipment, surface-to-air missile systems, and air bases on the Spratly and Paracel Islands, islands believed to be rich in oil and gas. By doing this, China’s regulation over the South China Sea’s commerce is more apparent. Specifically, the majority of Chinese vessels in the region disguise themselves as fishing boats but actually serve as Beijing’s maritime militia. Furthermore, by asserting dominance in the South China Sea, China seeks to diminish American partnerships with Southeast Asian countries like the Philippines and Vietnam.

If the US allows China to exert considerable influence over its Asian neighbors, the US will eventually lose footing and leverage in future negotiations. An increasingly powerful China would not only threaten American geopolitical interests but also the security of America’s allies and partners. This process can already be seen through China’s diminishing of Taiwan’s diplomatic status, appeal to the Global South, and efforts to replace the US as the dominant superpower.

Ambition for Innovation

Since the start of the 21st century, China has transformed from being a “technological backwater into an innovation powerhouse.”

According to Matt Sheehan at the Carnegie Endowment for Peace, three factors contribute to China’s meteoric technological advancement: large and semi-protected market, connections with researchers and companies, and capital invested in critical fields. By fulfilling the first factor, the Chinese government initiated the Great Firewall to block many American Internet platforms and allow Chinese startups and enterprises to prosper. In addition, to forge connections, China has sent numerous engineers to work at Big Tech companies like Apple and Google and engaged in projects with foreign scientists and professors.

Finally, benefiting from capital invested by foreign countries, China seeks to become the world’s fastest innovator in several promising fields, including AI. In 2017, Beijing initiated its National AI Plan that started pilot programs for autonomous vehicles, established machine learning majors for college students, and provided the police and military with advanced surveillance systems.

Future Anticipations

Despite its meteoric rise as a geopolitical hegemon, China has several domestic issues to be concerned about. These issues include high unemployment rates, lingering property crises, weak domestic demand, collapse of direct foreign investment, and more. Despite these economic slowdowns, China remains unhindered in its foreign policy front. In June 2023, China brokered a peace deal between Iran and Saudi Arabia, threatening the US order in the Middle East.

Also, China has frequently played mediator in the Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Hamas conflicts, while continuing to influence numerous lower and middle-income countries with the Belt and Road Initiative.

Furthermore, China’s investment into technology to increase its surveillance has also extended to many African nations that requested surveillance equipment, leading to several implications regarding privacy and human rights.

“Simply put, data collection conducted by the state with the technical support of its partners can impact human rights depending on where and under what conditions they source and use biometric data.” – Bulelani Jili, Research and Visiting Fellow

Conclusion

As it heads into its 75th year anniversary of the founding of the PRC, Beijing will continue to advance its subtle and multidimensional agenda, as its relations with Washington rest on a hinge that will define its power trajectory in the coming years.

Stay tuned for the 2nd article of this series about Russia.