A microscopic piece of machinery injected into someone burrows through layers of skin and cells to reach the very essence of humanity: our DNA. This perfectly crafted tool slices through segments of the DNA or even adds on additional pieces to suit the user’s need. While the human cells struggle to repair the alterations, the damage has already been done. In one fell swoop, a life-threatening disease ceases to exist. Doesn’t this sound like a work of science fiction?

This groundbreaking technology sweeping the academic community is called Crispr. First used on human cells in 2013, The Guardian compared Crispr to “a pair of molecular scissors guided by a satnav.” Although gene manipulation has existed previously, the technology stands out because it can not only remove malicious genes but also add entirely new pieces of DNA. Using non-reproductive somatic cells and animal models, researchers have worked to treating horrible diseases like sickle cell anemia, hemophilia, muscular dystrophy and cystic fibrosis by using this addition method. Although these immunities are not inherited by future generations, their reproduction in individual’s cells ensure the resistance lasts for decades. The ease of use and low-cost set Crispr apart from other genome editing tools, issuing in a host of new scientific possibilities.

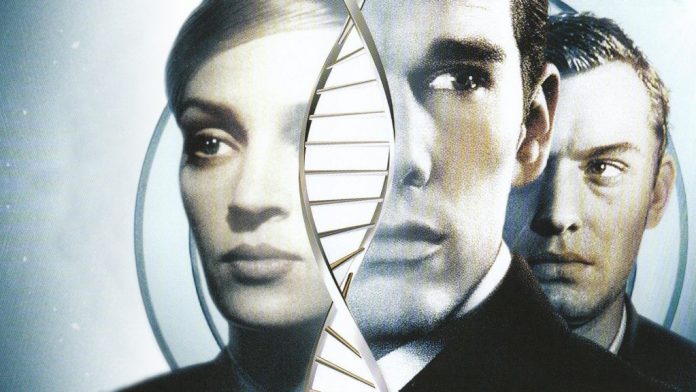

The powerful tools Crispr offers the field of genetics mirror the cult classic sci-fi film of the ’90s, Gattaca. Throughout an era in which DNA determines social status, Vincent, played by Ethan Hawke, grows up without any modifications and suffers from the obsolete illnesses of myopia and a congenital heart defect which tank his life expectancy to only around thirty years. Although Vincent dreams of becoming a famous astronaut, the only way he could join a space program was through impersonating a “valid” person without his genetic flaws.

One of the key dynamics within the movie is the dichotomy between the main character Vincent and his genetic donor Jerome Morrow. Although society treats Vincent as subservient due to his unaltered genetics, it is Jerome whose entire life suffers in mediocrity. Even with a genetic makeup “second to none,” Jerome never accomplishes anything notable, losing the gold medal in a highly publicized competition. Jerome cannot even succeed in ending his own life, only paralyzing himself from the waist down. Vincent excels where Jerome fails because of his tenacity and unwillingness to give up, traits incapable of genetic coding.

Gattaca highlights the next step for genetic innovation: the alteration of one-celled sperm, eggs, or embryo to seal genetic changes in the “germ line.” By permanently fusing these revisions into the DNA before replication, these immunities will be carried on for generations. However, the tactic of breaching this barrier issues in more questions of morality than finite scientific answers. The almost universal consensus since the 1970s has been that crossing the germ line violates moral codes and allows humanity to “play God.” In the quest for eliminating imperfections, the film argues we alienate those so powerful they can overcome physical and mental handicaps. A perfect example of this appears in a deleted scene from the final cut which highlights famous individuals who thrived despite genetic disabilities including Albert Einstein and Abraham Lincoln.

DNA testing not only brings up many difficult questions of ethics but also can backfire with horrible consequences. While gene treatments are intended to provide healing, an early trial of the therapy notoriously gave leukemia to a quarter of the patients treated.These specific issues were resolved, however, the devastating ramifications of gene editing gone wrong highlight the craft’s complexity.

Genetic innovations act as a double-edged sword, bringing both the possibility of curing diseases which affect millions and robbing us of our very humanity. What does the future for Crisper hold? Scientists at Sangamo Biosciences in California are currently testing a curve for HIV using somatic cell editing therapy, which would remove the need for antiretroviral drugs over a number of years. Crispr continues to represent 1984 as the future of modern science, issuing in the threat of a bleak future without proper countermeasures. While these advancements and innovations can help our society continue developing, humanity must move cautiously into the realm of new genetic sciences. Without carefully analyzing the ethical consequences of our future actions, humans might find ourselves destroying the very values that helped ensure our survival.

Sources:

http://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/may/10/crispr-genome-editing-dna-upgrade-technology-genetic-disease