Throughout the conflict in Ukraine, a predictable cycle of events has taken place. Russian forces launch attacks throughout Ukraine but fail to achieve any major success. Innovative methods, such as cyber-attacks or drone swarms, are used to asymmetrically deteriorate Ukraine’s ability to wage war. However, after a few weeks, Ukraine strikes back and routs the Russians in a series of engagements. Then, stalemate erupts and the cycle repeats.

This continuing pattern has lasted since Russia’s February 24th invasion of Ukraine – a bloody, ruthless conflict that has killed countless thousands of soldiers and civilians alike. Both sides have lost great quantities of men and materials, and everyone is looking to achieve victory in 2023.

In the last article, I uncovered how Russia’s status quo strategy to win the war – attacking Ukraine’s critical infrastructure and costly frontal assaults to seize small towns – has not yielded any significant results, and only cost Russia thousands of lives. For the second and final part of my Ukraine winter conflict coverage, I will cover how Ukraine will attempt to win the war this year.

Ukrainian Pathways to Victory

Despite Ukraine being on the receiving end of much of the fighting this winter – whether through the energy grid attacks or in the Donbas – there is evidence that Ukraine is ramping up preparations for a counteroffensive to seize the initiative.

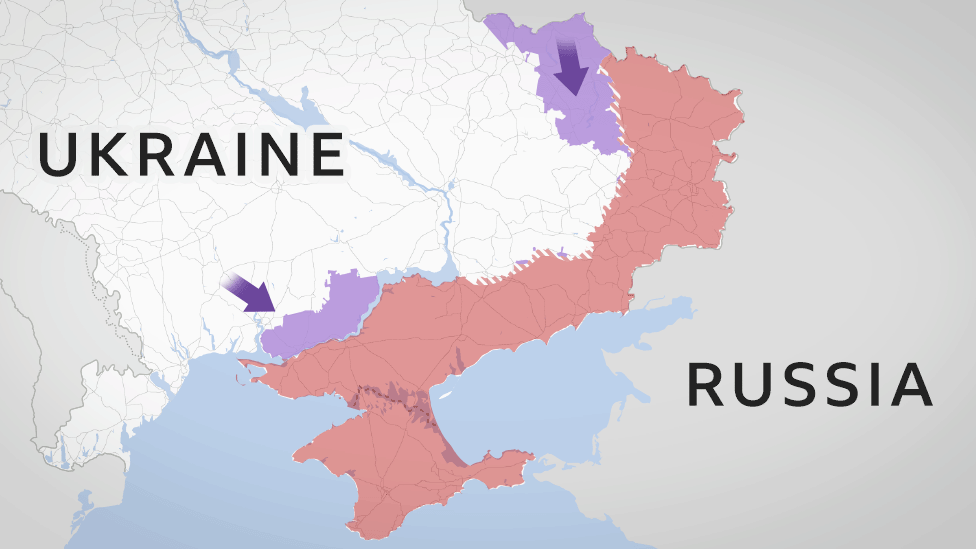

Ukraine has a lot to do with these counterattacks. Large swaths of its southern and eastern regions are under Russian control, and Ukraine has repeatedly stated they aim to liberate its entire country – including the Crimean peninsula, which has been under Russian control since 2014. It’s a tall order, but through foreign military assistance and military planning, Ukraine may be able to deliver crushing military victories.

Aid Shipments

First, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, or NATO, has been shipping billions of dollars worth of military aid to Ukraine. Starting on February 24th, NATO allies like the US, UK, Germany, Poland, France, and more have sent anti-tank weapons, ammunition, artillery howitzers, small arms, and more.

But one thing that was noticeably absent from Ukraine’s gift list was armored vehicles, including tanks. Armored vehicles are useful to protect and carry infantry to and from the battlefield, as well as to engage enemy troops with machine guns or cannons. They are an integral part of any effort to take enemy territory, which is the main war goal of Ukraine going into 2023.

The US and its allies initially balked at shipping armored vehicles to Ukraine – concerns abound about the time and effort required to train Ukrainian soldiers to man the vehicles, as well as the logistical cost of maintaining and equipping these new weapons. But by December, their mood has rapidly changed.

Starting in November, NATO countries began to promise deliveries of armored vehicles like the Bradley armored fighting vehicle (USA), Abrams tanks (USA), Challenger II tanks (UK), Stryker infantry fighting vehicles (USA), Leopard II Tanks (Germany, Poland, Spain) and Senator armored cars (Canada).

These new fighting vehicles were met with jubilation by Ukrainian soldiers, and it only enhances their warfighting capacity to take back territory seized by Russia early in the conflict. For a country that has lost thousands of tanks and fighting vehicles, this aid shipment came at just the right time.

In particular, the Abrams tanks represent the apex of 20 years of military tech development, with advanced sensors, firing systems, armor, and communications. The 31 tanks the Biden administration has pledged to Ukraine will significantly help their ability to destroy the Soviet-era tanks used by both sides. The American equipment will be a huge step up from the rusty 20th-century technology both Russia and Ukraine use on the battlefield now.

With combined arms tactics (utilizing separate components of an army or military to wage war) Ukraine can use its artillery to flatten Russian positions, then charge in with these new tanks and armored vehicles, whilst protecting their infantry. Additionally, the new equipment can be utilized in a tank hunting capacity, to launch long-range missiles to destroy Russian armored vehicles.

“It’s a powerful combination,” commented Bradley Bowman, a senior defense analyst at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. Although many of these new western vehicles will inevitably be destroyed, their mobility, armor, and firepower mean that Ukraine will have a significantly easier time taking back captured territory.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gray/AIYDMZ6UFJEGLI3KB7OII7ICUM.jpg)

New Counteroffensives

With the recent equipment pouring in, Ukraine has the opportunity to deliver a knockout blow – hopefully to end the war with its lost territory reclaimed. Elliot Ackerman, a geopolitics analyst, and former US Marine believes that “A strategy of maximum pressure may provide the only path to victory, requiring Ukraine and its allies to remain relentlessly on the offensive.”

A long-term war is simply too risky for either side to comfortably bet on. Given the heavy losses, Russia and Ukraine could quite literally bleed themselves white if the war continues for another few years. Past historical examples give us opportunities to see what engaging in prolonged conflict with a larger power looks like. When Finland engaged in a protracted, bloody conflict with Russia in the winter of 1939, they chose to maintain their defensive positions.

By 1940, the Russians had inflicted high casualties on the smaller Finnish army and then broke through, forcing the Finns into a negotiated peace settlement. Although the concluding peace saw Finland retain its sovereignty, it lost hundreds of kilometers of territory. If Ukraine waits around and neglects to launch any offensive action, Russia could build up its forces and wear Ukraine down in a war of attrition. Any chance of Ukraine regaining Crimea or the Donbas would be lost.

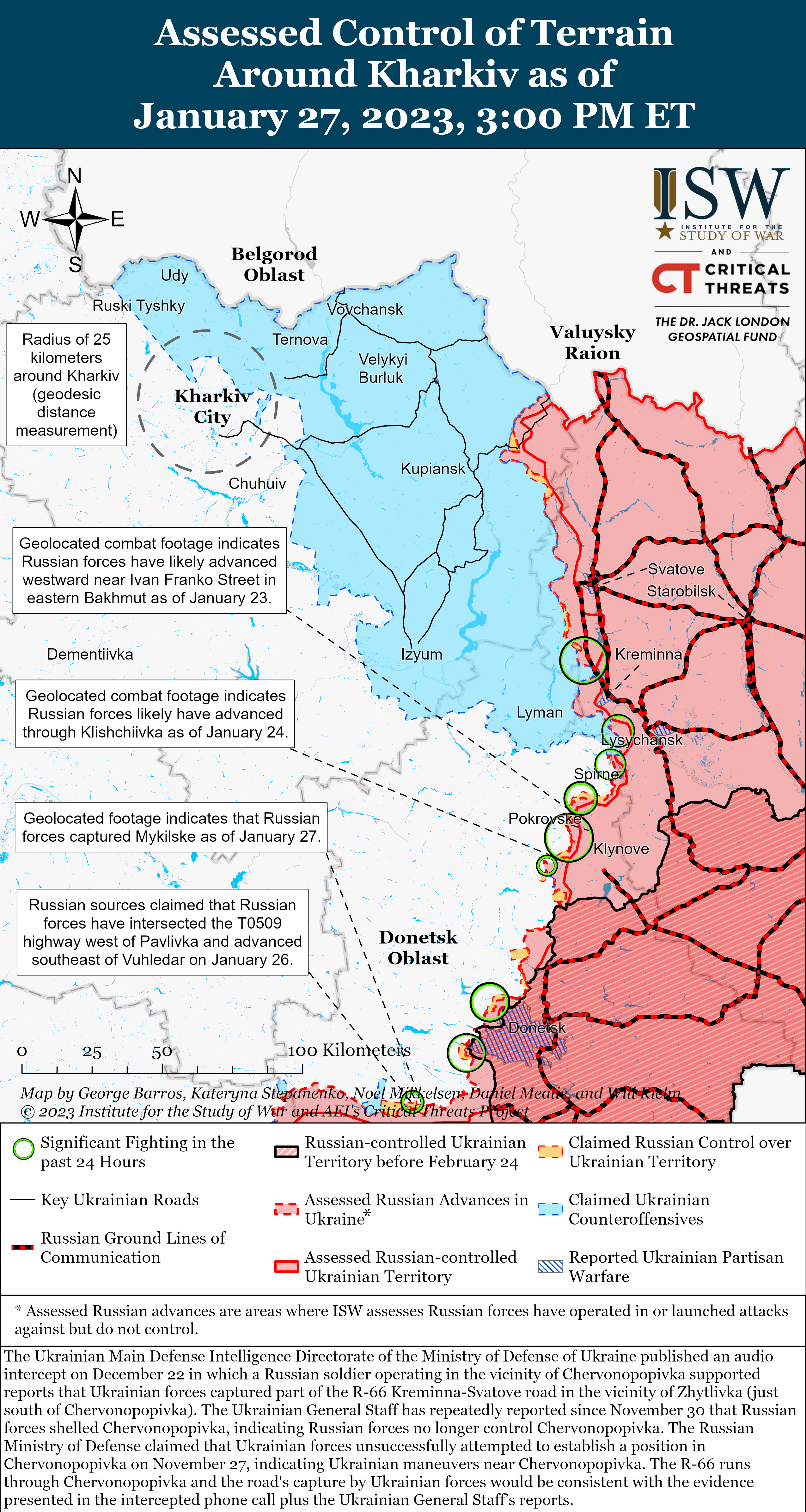

As of now, there are multiple fronts of battle that Ukraine could launch counteroffensives in. First is the Svatove-Kreminna axis, where Ukraine currently is attempting to sever the Svatove-Severodonetsk highway, which supplies tens of thousands of Russian troops to the south. The seizure of this highway would mean that Russian positions south, near the Severodonetsk-Bakhmut axis, and a subsequent halt to Russian offensive operations in those areas due to lack of supplies.

Currently, Ukrainian troops are launching a series of assaults to seize Kreminna, but they have gained little ground. With the new tanks and vehicles moving in, Ukraine might launch a renewed, more powerful offensive to take control of the highway.

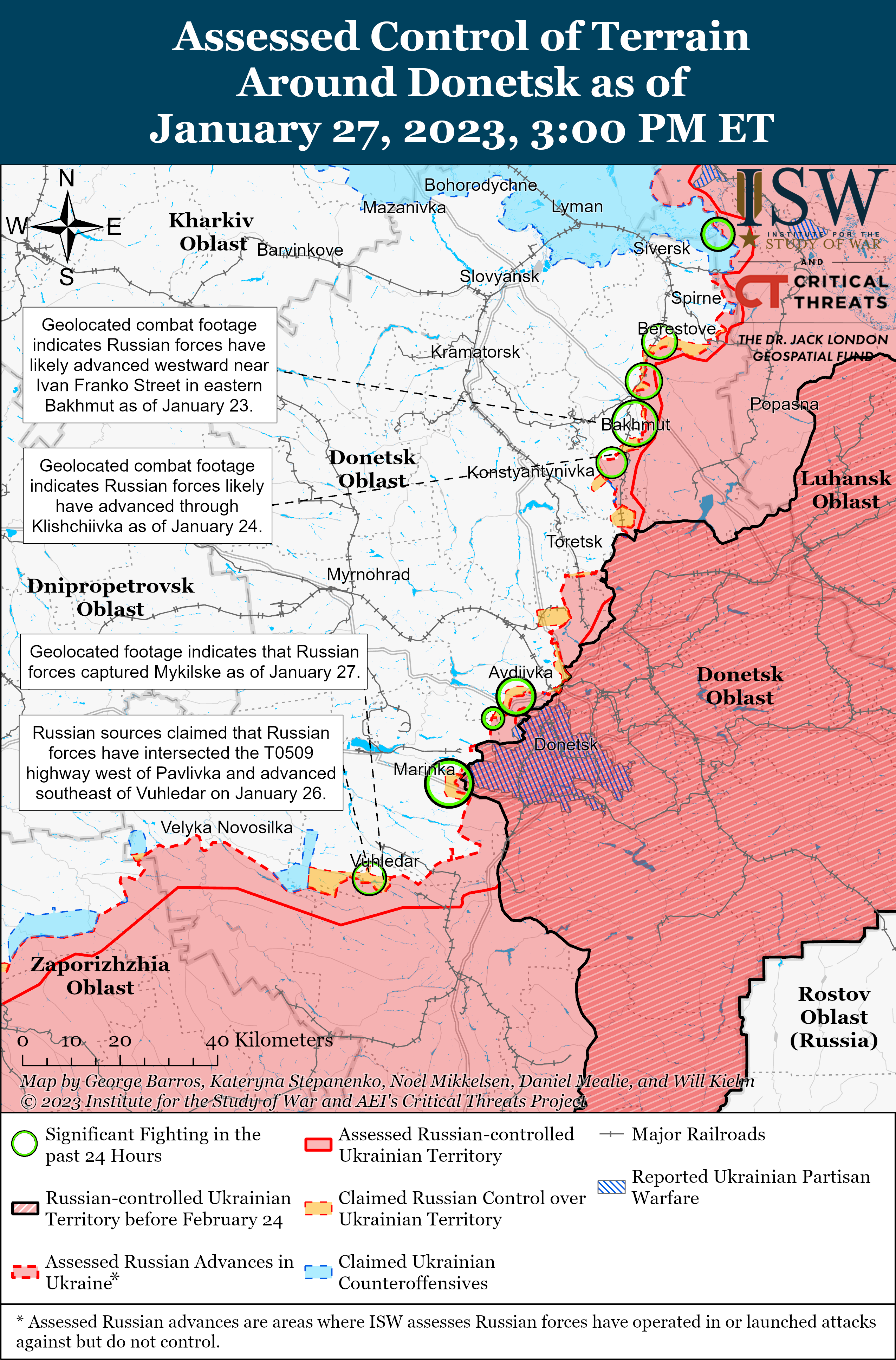

The second axis is the Severodonetsk-Bakhmut axis, a much narrower front, but in the region where Russia has concentrated most of its offensive capabilities. As I covered in my last article on the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Russia has seen limited success on this front. Ukraine is unlikely to counterattack here, as the Russian forces are too well dug in and have concentrated most of their troops and firepower in this location.

Third, there is the Bakhmut-Donetsk city axis, which has seen little territorial changes since the war began. Ukrainian troops here are extremely well dug in, as too are the Russians. The terrain here, with its sloping hills and proximity to urban clusters, means that a breakthrough on either side is extremely unlikely.

The Zaporizhia sector of the front line is much larger than the previous fronts, spanning an entire Ukrainian oblast – essentially a state. The flat terrain here means the newly arriving armored vehicles and tanks can be put to good use, and the key city of Melitopol, a crossroads of several railroad and highways, can be recaptured. Much speculation has arisen about a potential Ukrainian counteroffensive in this region.

A successful Ukrainian counteroffensive in Zaporizhia Oblast would mean Ukraine can threaten Crimea – a key war aim of Zelensky – by placing troops and artillery in range for an all-out attack. Russia has clearly recognized the potential severity of a Ukrainian attack in this region, as they are currently preparing extensive fortifications and redeploying veteran troops into the region.

The final front is the Kherson front. After Ukraine’s capture of Kherson, the capital of Kherson Oblast, both sides occupied opposite sides of the river, although a few Ukrainian troops did land on the eastern bank of the river. The Dniepr River, which flows between both sides, is too wide and deep to properly facilitate offensive operations.

The Wrath of Winter

The winds of winter are a double-edged sword in war. On one hand, the biting cold, snow, and resulting muddy conditions severely restrict combined arms operations. Soldiers get cold and burn energy faster, gasoline in vehicles freezes, and the roads turn into a quagmire.

But the winter can also aid offensive operations as well. As the temperature gets colder, worsening conditions mean that the ground freezes over, so that the mud turns into rock-hard ice and dirt.

“If the temperature falls below zero for any length of time, the frozen ground will provide opportunities for cross-country movement by tracked armored vehicles,” writes former British Army officer and land warfare expert Ben Barry.

Fresh winter equipment donations by Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the Nordic countries mean that Ukraine is well supplied for winter operations in the future. By contrast, Russia appears to lack significant winter clothing reserves for the hundreds of thousands of recently mobilized conscripts.

Given the massive influx of Russian conscripts, some may think that numbers would edge out. But the Russian conscripts will only be successful if they are still alive and ready to fight, and recent evidence suggests the Russian conscripts are poorly prepared. Russia’s logistical system, already strained, will go under further pressure from the freshly fallen snow.

The Ukrainians seem to be better prepared for the continuation of winter fighting, and then the beginning of spring fighting. The attrition rate of winter, sapping the strength of men and material, may soften up the Russians for a Ukrainian counteroffensive.

But whilst the temperatures are low enough to freeze the mud, that will not be the case for long. When March and April come along, the temperatures will rise back to the barely-above-freezing levels we saw in October and November. That means the return of an army’s worst enemy – mud. This muddy season, called Rasputitsa by Russians, occurs during the late fall and early spring.

Russia benefited from Rasputitsa when Napoleon and Hitler invaded centuries ago, but it will be unable to launch any major offensives after the temperatures rise. The same applies to the Ukrainians, which places them in an interesting predicament. The Ukrainians lack the firepower to launch an offensive now, but when they do receive the western arms shipments, the Rasputitsa season will prevent any sort of attacks.

Thus, it seems that major offensive action from both sides will see little success until the mud season ends. When Ukraine receives its new armored vehicles, it will have to wait until late spring or summer to utilize them.

But don’t think that fighting will slow down because of the frigid conditions. Countless times throughout history have wars continued – or even intensified – during winter. In WW2, Nazi Germany launched a massive winter offensive during the winter against American forces – the so-called Battle of the Bulge.

Ukraine has seen multiple winter offensives throughout history, from the invasion of Swedish King Charles XII, World War 1 and 2, to fighting during the Donbas war. The current tempo of bloodshed will not be as frozen as the ground.

Conclusions

It seems that going forward, Ukraine will slowly be attaining more and more of a military advantage over its embattled enemy. With pledges by Western powers of new military aid, the decrepit state of the Russian military, and opportunities for attack, Ukraine seems to be on the winning side of the war.

Ukraine will not have the weapons necessary to win the war until the mud season occurs, effectively neutralizing any chance of a large-scale counteroffensive for months. But Russia, beset by poor training, equipment, and logistics, will also see little success on a large front in the immediate future.

Major offensive action will resume after the mud season ends – and it will likely come from the Russian side first. Expect Russian offensive actions throughout mid to late spring, which will likely fail. When the new military aid arrives in Ukraine, and once the Ukrainian soldiers are trained to use them, a large-scale counteroffensive in the late spring or early summer is likely.

The success of that operation will decide on the training of Ukrainian troops in western equipment, coordination of large-scale combined arms offensives, as well as how poorly rotten the Russian military has become. Either way, don’t be lulled by the coming calm before the storm. When warm weather comes, the butcher’s bill will be high.