The Atypical Jobs of Typical People- Part II: Bill DeOre ’65

What if you offended people for a living? While that may not be on the  job description for an editorial cartoonist, it certainly comes with the territory. Bill DeOre, who graduated from Jesuit in 1965, knows better than most the trials and tribulations such cartoonists have to overcome. After all, he was a nationally syndicated cartoonist for The Dallas Morning News for over 30 years. He recently spoke with some of The Roundup’s staff about his journey from the bottom of his class to the top of the editorial page.

job description for an editorial cartoonist, it certainly comes with the territory. Bill DeOre, who graduated from Jesuit in 1965, knows better than most the trials and tribulations such cartoonists have to overcome. After all, he was a nationally syndicated cartoonist for The Dallas Morning News for over 30 years. He recently spoke with some of The Roundup’s staff about his journey from the bottom of his class to the top of the editorial page.

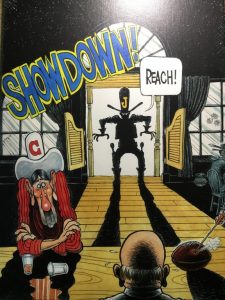

“I’m sure they’re wondering why I’m not in Huntsville [Prison],” DeOre joked about his classmates at Jesuit. He was certainly not the best student while he was here. “Jesuit in 1964 was not like it is today,” he told us. “There were no art classes.” The emphasis on only the core subjects left DeOre no way to develop his artistic abilities while he was in high school. Yet, there were those who saw his talent. “There were [priests] that saw I had this other ability that there was no channel for,” he recounted while also mentioning those priests who were not supportive. DeOre is inspired by the teachers that tried to help him fit in to give back to his alma mater, albeit in some atypical ways. He said that long as there is a kid at Jesuit who feels like he doesn’t fit in, he’ll  keep giving back because that was him once. While he may not have ever been able to give treasure, DeOre has generously donated his talent to the community in the form of illustrations by the athletic offices, including one of a showdown between a Ranger and a Cowboy, or each year’s senior prints.

keep giving back because that was him once. While he may not have ever been able to give treasure, DeOre has generously donated his talent to the community in the form of illustrations by the athletic offices, including one of a showdown between a Ranger and a Cowboy, or each year’s senior prints.

Yet, DeOre never knew that he wanted to be a cartoonist until much later in life. He said, “I was drawing all the time…sketching, messing around. Art, it was an affinity, but I never figured I’d be a cartoonist.” He did know that he enjoyed art, so he focused on that in college. “You have to look at your interests and what you think you might be able to get better at and be accomplished at and maybe someday make a living out of it,” he advised. After graduating with a Bachelors of Advertising Art and Design from Texas Tech, he was doing mostly freelance artwork for whoever would pay. Jobs were “few and far between.” He remembered, “If you did get a job, you got paid, but then you didn’t get paid for another month.” Fitting perfectly the description of the starving artist, he didn’t have a studio, drawing out of the back of a VW or at a friend’s place, working for ad agencies here and there. “I would take a job doing anything,” he admitted. Indeed, he eventually took a friend’s advice and got an extra job at The Dallas Morning News to earn an extra $100 a week.

Taking up work at the newspaper proved to be a very good decision. “When I went to work at the newspaper, they were hurting so bad for artists that had any skill or ability that…within a year I was an art director,” he said. Because he was involved with art at the paper, DeOre soon met the two editorial cartoonists, Bill McClanahan and Jack “Herc” Ficklen. “I thought their work was special,” he said about them. Liking that they just drew for a living, he soon realized that he wanted to do that too.

He would draw cartoons for McClanahan and Ficklen intermittently, balancing his other post with cartooning. It was very exhausting. He remembered how he took over as an editorial cartoonist, “I was in the right place at the right time. Both of them were close to retirement age, and it was also a time when newspapers were very strong.” Because the DMN had a policy of employing two cartoonists, DeOre was brought on along with Jim Palmer. However, DeOre observed, “[Palmer] wasn’t very happy here in Dallas.” Soon, Palmer moved away, giving DeOre an excellent opportunity. He told the newspaper that there was no reason to pay two cartoonists (no other paper was), and they agreed, letting him draw all cartoons, sports and political.

The daily life of an editorial cartoonist was a hectic one because he had to report to an editor each day. “Editorial meetings were like full blown MMA,” he acknowledged. DeOre would bring the editor an idea for what he was going to draw for the next day’s issue, and the editor would give him suggestions on what to change. Sometimes, however, the editors would give a little more than a suggestion. DeOre said, “These editors if they could draw stick figures, they would draw cartoons.” The reason for this? “Nothing will piss off management quicker than a political cartoon they don’t like,” he explained. Editors had to answer to management and the cartoonist to the editors, so management’s wishes trickled down to DeOre. He noted, “As time goes on, other ideologies trickle in.” Now DeOre understood what Herc Ficklen had once told him: “Your worst enemy will be the guys behind the typewriters [the editors].”

After a while, though, he figured out how to circumvent the “micromanaging” editors. He would bring 4 or 5 different ideas so that he could simply say, “Don’t like that one? How about this one? Don’t like that one? How about this one?” and so on, until the editors finally got sick of it and chose one. “I could do books on the cartoons I threw out,” he said. A cartoon, front and center in the editorial page, can put out a powerful message about the newspaper’s views, so the editors want that to be a message that won’t offend any powerful people in Dallas.

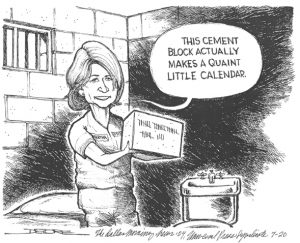

DeOre remembers one example when he managed to offend “every civic leader in Dallas.” American Airlines had been fined by the FAA (the largest fine in their history) for using car parts in wings. “I decided I was going to do a cartoon on American Airlines.” Long story short, the top guys at AA called the head of The Dallas Morning News, asking for DeOre to be fired. He said that local cartoons were always the most problematic. All in all, though, he said, “If I had to do it again, I have no idea what I’d do differently.” It was an atypical road to the editorial cartoonist for sure.