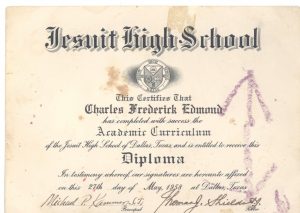

The entire packed auditorium at Fair Park focuses on Charles as he walks up to the stage, looking toward the principal of Jesuit High School, Fr. Michael Kammer, S.J. Shaking his hand, Charles gazes out into the crowd of students watching him. This is not just any other night; it is the class of 1958’s graduation, a night filled with laughter, joy, and excitement. But there will be mixed emotions for Charles.

After receiving his diploma, Charles sits back down, waits for the graduation ceremony to end, then walks over to his mother, who cleans people’s houses as a day-worker. Her first interaction with the Jesuit community had happened only hours earlier when she stepped into the auditorium for her son’s graduation. Rather than telling her he will attend a graduation party, Charles, taking off his cap and gown, hands them to her, then walks alone to his house only a few blocks away in a neighborhood unlike any his classmates live in. As he walks home, Charles glances back to the grounds of Fair Park, where the segregated State Fair had been held the past October. Charles’ mind races as he tries to figure out where to go, what to do next, what life holds in store for him.

This will be the last time Charles Edmond ’58 sees any of his classmates from Jesuit. But as one of the first two black students at Jesuit—and the first to graduate—his impact on Jesuit will help shape not only the school but the entire city of Dallas for years to come.

The Jesuits Resolve to Integrate

The decision to admit two black students into Jesuit arose in late 1954, after Brown v. Topeka Board of Education had declared school segregation unconstitutional earlier that year. Spurred by that Supreme Court decision, the New Orleans Province of Jesuits, which had been contemplating how to handle “interracial relations,” created a policy on integration in September of 1954, clarifying the Jesuits’ view on civil rights. In a letter sent from New Orleans on September 9, the Provincial highlighted the general principles which Jesuits were to follow, asserting, “All men, since they have been created by the same God, are sons of the same Eternal Father and hence enjoy the same fundamental human dignity and rights.”

Later in the letter, the Provincial strongly suggested that high schools would need to be integrated sooner or later, with integration coming “sooner in some cities than in others.” At that time, the New Orleans Province of Jesuits had high schools in New Orleans and Shreveport, Louisiana; Tampa, Florida; as well as Dallas, Texas.

Finally, on December 5, 1954, in a meeting of the New Orleans Province principals, a meeting that Fr. Kammer was attending, the chairman, Fr. D.R. Druhan, S.J., identified Dallas as an optimal location for the first integrated high school because “the populace would be fairly agreeable, the students have become prepared for it by various events held conjointly (debates, sodality meetings, etc.), the Bishop would favor it, and the number of Negroes (Catholic and academically qualified) would be few.” It was only a matter of time before the president of Jesuit, Fr. Thomas Shields, S.J., would be notified about the plans.

Thomas J. Shields was born in 1900. In 1937 Fr. Shields became provincial of the New Orleans Province of the Society of Jesus, and he held this position until 1944, when he decided to take on the responsibilities of rector and president of Loyola University New Orleans. Fr. Shields began partially integrating the university in 1950, while attempting to make as few waves as possible in the very segregated city. He believed that fully integrating at once in a predominately segregated city could be disastrous, and took extremely cautious steps when integrating Loyola. These methods of gradual, careful integration influenced Shields as he took on the role of president of the first high school in Dallas that would desegregate.

A few months later in March of 1955, Bishop Thomas Gorman, who had become bishop of the Diocese of Dallas in 1954, contacted Fr. Shields, asking him to consider admitting Arthur Allen, who was the son of “the most prominent Catholic negro in the Diocese.” Fr. Shields, along with Fr. Kammer and the rest of Jesuit’s administration, was eager to integrate, telling the Bishop that they “had already decided to admit negro students.”

Arthur Allen himself relates how his enrollment came about, recalling a conversation in 2000 he had with Stanley Marcus, president of Neiman Marcus during the 1950s. “Stanley Marcus and my father were having lunch at the Community Chest board meeting. The subject of their kids came up and Dad mentioned that he had three kids in college and one in a little school in South Dallas, St. Anthony’s Catholic School. Stanley was interested as to what Dad’s plans were for high school, and the plan was hatched between the two for Arthur to be a test case for Jesuit in 1955.”

Arthur applied, passed the entrance exams, and was accepted into Jesuit High School. Concerned that selecting only one black student to integrate the school might become unfortunate should that single student have difficulties succeeding, the school administration thought it important to find another black student with excellent academic credentials to ensure the success of the integration process. They selected a student named Charles Edmond, who had already started his freshman year of high school at St. Peter’s Catholic School, an all-black Catholic school located in the State-Thomas area of Dallas, which is today part of Uptown. And, as it turned out, both students did quite well and had success at Jesuit.

A Quiet Event Becomes a Front-Page Story

September 1 – 2, 1955, marked the first days of integration at Jesuit High School, when Arthur and Charles were admitted. Originally, the school administration had agreed to “give the admission of these students no publicity whatever,” but when a student told his mother that a black student was at freshman orientation, the mother protested, indignantly contacting the various newspapers and radio and television stations. In a city where segregation in school had gone virtually uncontested, this major change revealed cracks in the Jim Crow way of life.

Although Jesuit tried to discourage the publication of the events, attempting to avoid trouble that might, among other things, hinder enrollment, the Dallas Morning News, realizing how significant Jesuit’s integration was in a completely segregated city, decided to publish their report, and everyone else followed. On September 3, 1955, an article printed prominently on the front page of the Dallas Morning News publicized for the first time the integration of Jesuit, and later the same news would be circulated in the Dallas Times Herald, on radio stations, and on television.

The news story was not altogether accurate, however. In the article, the News reported that “it was the first time in Jesuit’s 42 year in Dallas that Negroes had been accepted,” but in fact Jesuit was only entering its thirteenth year, having been founded in 1942. Later in the article, the writer stated, “One registered for the tenth grade, and the other the eleventh,” but these details were incorrect, since Arthur was entering as a freshman and Charles, as a sophomore.

Though the article’s news might have been “shocking” to some people, the effect was somewhat marginal to the Jesuit community. Mr. Jack Eifert, who has taught at Jesuit since 1955, recollected, “There were two families that withdrew their sons from Jesuit, and one of them came back.” Bringing two black students into the Jesuit community was not a perfectly accepted change, but it was something radically new for Dallas and would certainly over time contribute to the city’s rethinking of its codes and regulations.

Cautiously Entering a New World

On September 14, 1955, two weeks after Arthur and Charles first walked through the front doors of Jesuit, Fr. Shields sent a letter to the Provincial reporting how the admittance of the two students had affected the school. In his letter, he explained, “The [white] boys accepted the two negro students in a wonderfully fine spirit,” and added that there was “no difficulty whatever.”

Aware that Jim Crow laws were in almost every part of their lives, Fr. Shields and the rest of the Jesuit administration had to figure out how to grapple with the reality of a segregated world while still integrating students into Jesuit life. Regarding the social interactions of Arthur and Charles, Shields noted, “The acid test came when, a few days after school started, both boys went out for football practice, the one for the Freshman team, the other for the ‘B’ team. They were fully accepted by team mates; again, no problem whatever. Both were told, however, that in the event we are playing a school which refuses to play against a team with a negro on it, they will not be on the bench or in game. Both boys,” he added, “fully understood.”

Furthermore, Shields revealed the approaches of the school’s Mother’s Club and Dad’s Club, stating, “The negro mothers are to be accepted as full members of the Club with all rights and privileges, but the Lady President is to inform the negro mothers in a private conversation that they should not expect invitations to events held in hotels, for the hotels do not admit negro people. In the event of social events held in the homes of members, the negro mothers are not to expect invitations unless the hostess, i.e. the lady of the house, should issue the invitation.” The Dad’s Club made no restrictions, extending “all rights and privileges to the fathers of the negro men.” Shields’ letter also states that one of the officers of the Dad’s Club thought “it would be worthwhile” to have Mr. Allen give a talk at a club meeting.

Jesuit was entering a new world by integrating its school. It was doing something no other high school had dared to do at this time in Dallas, something that could have success or utter failure. However, Jesuit did so carefully, in order not to create too much controversy. As a result, the issue of how to involve the new black students in the social life of Jesuit, when some of that social life inevitably would take place outside the confines of the campus or when some of the social life would require more intimate physical contact, conflicted with the social habits of the time in a city that was still strictly segregated. In his letter to the Provincial, Fr. Shields stated, “The negro boys may join any and all societies and activities, but they have been informed, and fully understand, they will not be invited to dances or such social activities.”

It would take the experiences of two black students to break through those social habits, to show that the new world Jesuit had just entered was not an extremist notion, but actually an advantageous system that would be eventually used throughout the entire country.

Arthur Allen at Jesuit High School

Though Arthur Allen ’59 became over time a very popular and well-respected student at Jesuit, his initial feelings about the high school were not positive ones. From the moment Arthur heard he was going to attend Jesuit, he resented it. “I didn’t want to attend,” Arthur explained, “and my family’s decision caused alienation between my father and me that lasted for many years.” Arthur went on to describe how he “didn’t know anyone at Jesuit, [and] it wasn’t near my neighborhood.”

During his freshman year at Jesuit, Arthur remembers being the object of “snide remarks” by some of the faculty and parents. Acknowledging what Arthur experienced, Mr. Eifert reported, “To the best of my knowledge, there was no prejudice by scholastics.” However, Arthur’s peers were “always nice.” By his sophomore year, Arthur began enjoying Jesuit more, mentioning that the “students were absolutely accepting of me, [but] sometimes parents and teachers [made] pointed remarks.”

Unlike Charles Edmond, whose neighborhood was, according to him, tolerant of his enrollment at Jesuit, Arthur received some backlash from his own community. Arthur remembered how, when he got home from Jesuit, he returned to “a totally different culture,” where his neighbors would ask him, “You too good for us? You going to talk white now?” Other consequences emerged because of Arthur’s integration of Jesuit, including one nearly injurious incident. “Two days after the news reported that Jesuit would be integrated, my mom and dad and I were watching TV when we heard a loud boom,” recalls Arthur. “A stick of dynamite had hit the house, bounced off, and landed on our neighbor’s porch, knocking it off its foundation.”

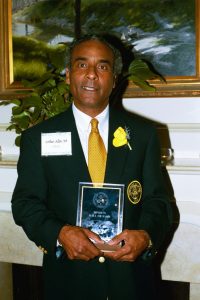

Running on the track team, Arthur showed his dominance, breaking records in the long jump, and placing in hurdles, relays, and the 100-yard dash. A successful player on Jesuit’s varsity football team, Arthur competed with teams from all over Texas, carrying over 200 yards in one game and scoring 25 points in another. Arthur’s football prominence merited him The Dallas Morning News’ “Back of the Week” and a position on the All-Greater Dallas High School Football Team. His wide range of athleticism eventually earned him a four-year scholarship to Marquette University and recognition in the Jesuit Sports Hall of Fame.

Complying with some of the Jim Crow ways that were still in effect, Arthur recalls that the Jesuit administration, urged by some parents, told Arthur not to attend the Jesuit Prom. Before the Prom, the principal approached Arthur, advising him to cancel his plans, fearing, says Arthur, that someone might ask his date for a dance or that “God forbid, I would ask someone else’s date for a dance.” Arthur responded to this prejudice by skipping the Jesuit Prom and going to Lincoln High School’s Prom, which was near his home.

While the discrimination Arthur received at school was disheartening, the racism he had to deal with from other schools was like nothing he had ever experienced. One thing Arthur regretted was the “long walk,” the trek he had to make to the principal’s office on Friday if a school had complained about playing against him. Arthur recalls, “I would be given the choice to sit out the game or have the team forfeit. After these meetings I would go downstairs to the locker room and cry. Then, I would come back up.” According to Arthur, “Some schools wouldn’t play Jesuit if I even suited-up with the team. Since Jesuit didn’t want to forfeit a game, I didn’t participate. Usually the priests would ask me to make the decision, which was, of course, a huge responsibility to put on a young boy.”

Jim Hopp ’59 recalled what he remembered about that time, saying, “at least one of our football games was cancelled because the team from a town south of Dallas refused to play Jesuit since we had an African-American on our team.” Additionally, according to Mr. Eifert, “When [Arthur] couldn’t play as junior or senior on varsity because the other team wouldn’t allow it, he played on the JV, particularly when we played Catholic schools.” Mr. Eifert remembers one particular game when the JV played Muenster Catholic High School: “The score at the end of the first half was Jesuit: nothing; Muenster: nothing; Arthur Allen: 21.” Unfortunately, in the second half Arthur was injured, taken to the hospital, and Jesuit lost the game 22-21.

When Arthur was allowed to play, he experienced how Jim Crow laws had snuck into almost every part of life. On route to some games, Arthur was denied service at restaurants where the team would intend to eat; their solution was to leave the restaurant and travel until they found a restaurant for Arthur to eat at with them. Motels where the team stayed were segregated, meaning Arthur had to go to a different motel than the rest of the team. Sometimes, but not always, once they made it to the game, opposing teams’ fans would “hurl obscenities, throw Coke on me, and spit on me.” Fortunately, Arthur was protected by his fellow teammates like fullback Bob Cahill, who Arthur said was “my protector [because] when something happened, he was the enforcer and would mete out justice.”

Despite the challenges and frustrations, Arthur made the most of his Jesuit experience, studying hard while still participating in football, baseball, elocution, theater, and track. “I liked my athletic prowess and my public speaking talent and the affirmation they gave me with my peers,” stated Arthur. “It taught me how to deal with people, to make friends, to form partnerships.”

In 1994, Arthur was honored with the Jesuit Distinguished Alumnus of the Year Award. Arthur, long active in Jesuit affairs, has served as president of Allen & Associates Inc.; he and his wife, Dee, have two children.

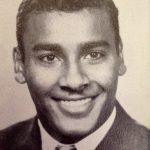

Charles Edmond at Jesuit High School

The other black student admitted at the same time as Arthur, Charles Edmond, grew up in a poor background in South Dallas, attending St. Anthony’s. During his freshman year of high school, he attended St. Peter’s.

Charles was first told about his future enrollment at Jesuit during the spring of 1955, while he was a ninth grader at St. Peter’s. The nuns at the school, sensing the magnitude of the issue, gave him the momentous news with the instruction, “Just hold on.”

After hearing the life-changing news, Charles acted nonchalantly, but soon fear rose in his mind, mainly because he didn’t want to “let people down.” His mother, sensing his apprehension, became very supportive, making sure he wasn’t anxious but rather proud to be able to get a good education. His older brother and younger sister also were aware of the news, but no one other than that was informed because Jesuit did not want a community uproar focused on them. “At that time,” recollected Charles, “all the civil rights issues began to boil over and I wasn’t sure how Jesuit was going to react to me.”

As if the first day at a new school wasn’t frightening enough, Charles received little-to-no instruction or welcome when he entered the building for the first time. Adding to the trepidation was the fact that he was a sophomore entering into a school where “those students had been together freshman year, so they knew each other and I didn’t know many of them.” The only person who talked with Charles was Fr. Kammer, who indicated that, if he had any problems, he make sure to come to see him and talk about it. “I felt kind of isolated,” noted Charles. “I was quiet and didn’t participate in class. I just sat and tried to learn, and only later on did I begin to develop friends.”

The isolation did not end at school however. Before and after school, Charles would take the bus by his neighborhood to downtown Dallas then transfer to another bus, a bus also occupied by fellow Jesuit students. Nevertheless, while his classmates sat in any seat they chose, Charles was forced to sit in the back, due to relentless Jim Crow laws. “Here were students that I knew and associated with at school, and I had to sit apart like I didn’t know them.” Despite feeling isolated both in and out of school, Charles received encouragement from his classmates and teachers. He was made a sophomore class vice-president, and reminiscing, Charles lightheartedly asserted, “I don’t know how I got that.” Referring to the election, Fr. Shields, in his letter to the Provincial, called it “the finest compliment to student spirit.”

Charles also said that the teachers helped him out a lot, especially his geometry teacher, who he believes passed him “just by the luck of it.” Only one teacher, the counselor, gave Charles trouble, telling him that he would not “make it in college,” perhaps, added Charles, because he had average grades.

Charles’ only interaction with other students outside of school was while he was in the marching band, where he played the bass drum. “I did not have a musical background,” Charles jokingly remarked, “and Mr. Coleman [band director] needed a French horn player so he asked me to try it, the hardest instrument.” However, Charles decided to play the bass drum, an instrument which he played with the marching band during home football games at the stadium in Highland Park.

One of the rare instances when Charles associated with another student outside of school was when a classmate in his trigonometry class, knowing Charles was good at math, called him for help. Like her son, Charles’ mother never went to any social events, and she never even went to the school building because she felt “uncomfortable” during a time when blacks were not accepted in a majority of places.

Essentially, though, Jesuit saved Charles’ life. “My neighborhood was of low income, 100% black, and there were gangs,” recalled Charles. “Jesuit was like a safe haven because I left home in the morning and I was there in the afternoon because I was in band. I’m glad that pulled me out of the neighborhood for a while because I think I would have had problems going to other schools in the neighborhood.” In fact, one time while Charles was attending a backyard party, he and a friend were attacked by a group of men, a group that Charles could have been a part of if he had not gone to Jesuit.

As a member of the St. John Berchman’s Club, Charles furthered his spirituality at Jesuit, having been an altar server since his childhood at St. Anthony’s Catholic Church. “I was a member of the altar boys because I had always been an altar boy since I was very little,” explained Charles. “I would come up on the weekend and the altars would be lined up where the priests could say Mass.” Charles even received the Sacristan Award one year, denoting great service and work for the Church.

One regret Charles still holds, however, is the fact that he never bonded with Arthur, the other black student who broke the segregation barrier at Jesuit. “I never bonded and I wish now that we could because we could talk about what he was feeling and what I was feeling,” revealed Charles. “We never bonded even though I knew of him, and I knew his father was a well-to-do person, but we never associated, and very seldom did I see him.”

Overall, Charles enjoyed his time at Jesuit. “I envisioned something similar to Jackie Robinson [and] what happened when he integrated the major leagues, the harassment he got, but at Jesuit there was no racial backlash or bullying. Jesuit grew on me and I enjoyed it.”

John Stack ’58 was in many classes with Charles and shared his thoughts on the time they spent together in high school. “I felt totally at home with him,” recalled Stack ’58. “Even now I remember that I was proud that he was part of our class. I was delighted that Jesuit had led the way on this issue.”

After graduating from Jesuit, Charles went to Grambling State University. Originally planning to major in English, Charles switched because he did so well in math, and ended up graduating cum laude. Charles moved to St. Louis and worked as a secondary teacher of mathematics, activities director, athletic director, and dean of students, retiring as a high school assistant principal. During his time as math teacher at University City High School in Missouri, Charles was the first African-American male teacher on staff.

Today, Charles lives with his wife, Ruth, leading a very peaceful and laid-back life. They still enjoy going on trips and keeping in touch with their son and daughter.

Looking Back to 1955 from Today

While blacks were undergoing discrimination around Dallas by unfair Jim Crow laws, Jesuit High School was establishing itself as an example, although not a perfect one, of integrated, unbiased education that stood out in a nation—and city—where intolerance and exclusion was still the norm. Within a few years, after both Fr. Kammer and Fr. Shields had departed the school in 1959, the idea that a black student should “not be invited to dances or such social activities” faded away, and students would be accepted at all Jesuit activities regardless of race.

Looking back on the experience, classmates and teachers of Charles and Arthur realize the positive effect their attendance at Jesuit had on everyone.

Jack Harper ’58 recollected about his time with Arthur and Charles, saying, “In thinking back about it I am rather surprised that it was not a really big issue with the students. It was all very natural and I guess I was unaware of what a groundbreaking situation we were involved in.”

Joseph Murphy ’59, a teammate of Arthur in football, realizes now that “he put up with a lot of bull,” and added that “he was a tougher person than I.”

Fr. Richard McGowan, a teacher at Jesuit during Charles’ school years, remembered a particular incident during a football game: “The Jesuit band walked out single file along the sideline before the game, and Charlie was carrying the United States flag, quite an honor. And I heard one Highland Park mother say to another, ‘Well, the Catholics are showing their true color today.”’ While the mother’s remark may have been aimed at mocking Charles and Jesuit, perhaps what it showed is the authenticity of Jesuit’s efforts to embrace civil rights, that discrimination would not be tolerated at school or on the field.

Arthur’s and Charles’ influence on Jesuit was so compelling that Fr. Kenny Buddendorf, S.J., who taught at Jesuit from 1955-58, recalled the time a few years later at a debate tournament when Pat Hunter, the debate coach, refused to go to a tournament because they would not let him take the black student [debater] with them.

A senior at that time who later became a priest, Fr. Gerald Fagan ’56 summarized integration at Jesuit as “a prophetic voice. It was speaking out very strongly; it was speaking out for equal rights, equal education, equal opportunities, and the dignity of all people.”

By opening its doors to students like Charles Edmond and Arthur Allen, Jesuit High School was leaving “the dark and desolate valley of segregation,” as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. described the Jim Crow world that had enveloped the country in his “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington in August 1963. While Dr. King said that the pursuit of civil rights in “Nineteen sixty-three is not an end but a beginning”; for Dallas Jesuit, 1955 was the beginning of change in the struggle against the now-outdated customs of segregation, a beginning pioneered by two African-American students and the faith of a school community joining together to echo Dr. King’s famous words: “With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day. ”

1955: Jesuit High School and the Struggle for Civil Rights – A Three-Part Series

Sources for this series

“2 Negro Boys Registered by Jesuit School.” Dallas Morning News 3 Sept. 1955.

Allen, Arthur. “Arthur Allen’s Talk.” Jesuit College Prep, Dallas. 2006. Lecture.

Anderson, R. Bentley. “Black, White, and Catholic: Southern Jesuits Confront the Race Question, 1952.” The Catholic Historical Review 91.3 (2005): 484-506. ProQuest. Web. 27 Sept. 2006.

Anderson, R. Bentley. Black, White, and Catholic: New Orleans Interracialism, 1947-1956. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2005.

“Kenny Buddendorff, S.J.” Telephone interview. Dec. 2011.

“Color Line Declared Still Law in Texas.” Times Herald [Dallas] 20 Aug. 1955.

Bogen, Harvey. “Negro Group Plans Fair Gate Pickets.” Dallas Morning News 17 Oct. 1955.

Dallas Business Journal, ed. “Stanley Marcus, 1905-2002.” Dallas Business Journal (2002). Web. 8 Mar. 2007.

“Edmond, Charles.” Personal interview. December 2011.

“Jack Eifert.” Personal interview. Dec. 2011.

“Exploring the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial – The Washington Post.” Washington Post: Breaking News, World, US, DC News & Analysis. Ed. Kat Downs. 22 Aug. 2011. Web. Aug.-Sept. 2011. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/special/lifestyle/mlk2011/interactive-memorial/>.

Eyes on the Prize. Prod. Henry Hampton. PBS, 1987. DVD.

George, Charles. Life Under the Jim Crow Laws. 2000.

George Allen: An Oral History Interview. March 1981.

“Jerry Fagin, S.J.” Telephone interview. Dec. 2011.

Juanita Craft: An Oral History Interview. Dallas Public Library. 1979

Fowler, Wick. “Attorney Cites Edict of Court.” Times Herald [Dallas] 25 Apr. 1956.

Harper, Jack. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Hopp, James. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Killingsworth, Blake. “”Here I Am, Stuck in the Middle with You”: The Baptist Standard, Texas Baptist Leadership, and School Desegregation, 1954 to 1956.” Baptist History and Heritage (2006). Goliath Business News. Web. 8 Mar. 2007.

King, Martin Luther Jr. “I Have a Dream.” American Rhetoric: The Power of Oratory in the United States. Web. Sept. 2011. <http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkihaveadream.htm>.

Linden, Glenn M. Desegregating Schools in Dallas: Four Decades in the Federal Courts. 1995.

Murphy, Joseph. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

“McGowan, Richard, S.J.” Telephone interview. Dec. 2011.

Morehead, Richard M. “Integration Thus Far Affects Few in State.” Dallas Morning News 16 July 1955.

“Negroes Won’t Be Moved.” Times Herald [Dallas] 24 Apr. 1956.

“Pastor Calls for Help to Uphold Segregation.” Dallas Morning News 6 Mar. 1956.

Pettibone, Jerry. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Pitts, David. “Brown v. Board of Education: The Supreme Court Decision That Changed a Nation.” Issues of Democracy 4.2 (1999): 38-46. Web. Jan. 2012.

Raffetto, Francis P. “Negroes Ignore Fair Picketing.” Dallas Morning News 18 Oct. 1955.

Schack, William. “Neiman Marcus of Texas: Couture and Culture.” Commentary Magazine (1957).

“Segregation Signs Up Here Despite Order.” Times Herald [Dallas] 10 Jan. 1956.

Seymore, Kelly B. Times Herald [Dallas] 3 Apr. 1988.

Shields, Thomas J. Letter to Provincial. 14 Sept. 1955. MS. Dallas, TX.

Shields, Thomas J. Letter to Provincial. 31 Mar. 1955. MS. Dallas, TX.

Shipp, Bert. “School Integration Not Expected In Fall.” Times Herald [Dallas] 22 July 1956, sec. B. Print.

Stack, John. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Taliaferro, Mike. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Williams, Juan. Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years, 1954-1965. 15th Anniversary ed. New York, NY: Penguin, 1987.