As I drive south down Inwood Lane in my brand-new 1955 turquoise Chevrolet Bel Air, I look in the rear-view mirror and glance out into the open green pastures behind me, unoccupied by any obtruding buildings, devoid of car exhaust. Seven years from now, in the fall of 1962, this cotton field will be the site of the newly constructed Jesuit High School.

It is a beautiful fall Saturday morning in October, one of the first cool days after one of the hottest summers ever in Texas. When I turn left onto Forest Lane, the window rolled down, my arm resting along the door, I peer forward toward the corner of Preston and Forest, small fruit stands and country stores surrounding the intersection. Years from now this almost uninhabited area will become a frequently traveled zone of shopping centers and restaurant chains.

Rock Around the Clock: Driving Central Expressway South to Jesuit High School in 1955

Reaching Central Expressway, I ease up to the stop sign and prepare to turn right. Ahead in the distance, I spot a few cement trucks heading toward the new residential community of Hamilton Park.

Turning the radio knob to KLIF, I hear the soothing voice of Kenny Sargent, the radio host. “This next song,” Kenny says smoothly, “is on the top of the U.S. Charts. Here is ‘Rock Around the Clock’ by Bill Haley and His Comets.” One, two, three o’clock, four o’clock rock, five, six, seven o’clock, eight o’clock rock.

Listening to the music, I cruise the left of two lanes headed south down the newly completed Central Expressway, passing the turnoff to Walnut Hill Lane. In between grassy fields, I notice ahead the recently constructed nine-story Meadows Building, still a couple miles away but towering over all the other small, scarce structures on the side of the road. Within a decade or two, this lofty building will be dwarfed by the emergence of one much taller high-rise building after another.

Kenny Sargent’s voice begins again as the song on the radio concludes. “Last night, on America’s favorite program, I Love Lucy, Lucy got herself into trouble when she stole the cement slab of John Wayne’s footprints,” chuckles Kenny. As the dull drone of the car motor suppresses his mellow voice, I gaze into the vast pasture beyond Loop 12, unaware that 100 acres of the land will later become NorthPark Shopping Center.

As I continue driving down Central Expressway, I look into my rear-view mirror, observing as the Meadows Building shrinks into the horizon. Ahead, the flying red Pegasus atop the Magnolia Petroleum Building enters into my view as I proceed closer to downtown Dallas. Near the Magnolia Building stands the 40-story Republic National Bank, a gleaming structure just one year old. A few miles away from me this October day, a woman named Juanita Craft is leading a protest against racial segregation at the State Fair. The Chordettes’ song “Mr. Sandman” plays over the hum of the car. Mr. Sandman, bring me a dream. Make him the cutest that I’ve ever seen. Marveling at the skyscrapers of downtown, I exit Central Expressway, turning right onto Blackburn.

Easing up to the corner of Blackburn and Turtle Creek, a four-story building sits atop a hill on Oak Lawn, just a short distance away. Enormous elm and oak trees enveloping the streets and homes around me, I drive near Holy Trinity Catholic Church and by a number of stores, one a small coffee shop. As I climb up the hill and turn toward the parking lot, the archway above me proudly declares “Jesuit High School.” Countless windows line all sides of the four-story red brick building, and a large flight of steps welcomes students as they make their way to the main entrance of the school. High above the trees and buildings around it, an elegant dome topped with a cross crowns the school, directly above the central doors.

As I turn into the parking lot, the song by Fats Domino, “Ain’t That a Shame,” which is growing in popularity after Pat Boone’s cover of it, blares from the radio. You made me cry when you said goodbye. Ain’t that a shame, my tears fell like rain. Ain’t that a shame, you’re the one to blame.

A month ago in early September, for the first time, two black students were enrolled at Jesuit. These are the first blacks to integrate any school, public or private, in the city of Dallas. Each day these two young men, one a freshman and the other a sophomore—approximately the same age as Emmett Till when he was lynched in August in Mississippi—go back to their communities governed by racial segregation and Jim Crow laws—laws similar to those in Money, Mississippi, where two men who murdered Emmett Till walked away unpunished for their crime of murder. While the lyrics of Fats Domino’s song remind one of the blues of a broken heart, the real shame lies in the racial inequality of Dallas in the 1950s, during an era of continuing discrimination and Jim Crow.

Dodge ’em Scooter: Keeping the Races Apart in Dallas

Dallas’s acceptance of Jim Crow laws traces back to the period after the American Civil War, once Texas emerged from the Reconstruction era. During the very beginning of the Reconstruction, on June 19, 1865, subsequently known as Juneteenth, news had been brought to Texas that formally emancipated all slaves. To compensate against the new-found freedom of slaves, once Reconstruction ended, Texan lawmakers—like lawmakers all across the South—eventually adopted Jim Crow laws, legalizing segregation. Nearly 100 years after emancipation, these practices still continue throughout the South, including Texas and, of course, Dallas.

Conforming to the racial codes and laws like so many other cities across the United States, Dallas readily enforces Jim Crow laws. Up until the 1940s, one such law enforced was the mandate of all-white juries. Being the same kind of juries used during bigoted trials such as that concerning Emmett Till’s murder, these juries predominately ruled in favor of any white man over a black man. In a time when the skyline of Dallas was rapidly changing, however, cracks were beginning to appear in the Jim Crow way of life. While Jim Crow culture was strong, by the mid-1940s juries in Dallas were at long last integrated, allowing blacks to participate, as whites did, in courtroom events.

In addition, during the 1940s, whites-only primaries across the South and in Dallas prevented blacks from voting. Since Reconstruction, all states in the South were governed by Democrats and in Texas the primary for Democrats was for whites only. This law, designed to hinder the role of blacks in society, remained in effect until 1944, when the Supreme Court ruled that white primaries were unconstitutional. Another crack had appeared in the Jim Crow structure. However, major steps in racial equality still have to be made, as evidenced by the current conditions of the 1950s.

One of Dallas’s worst problems in the 1950s is school segregation. Even though a year ago in 1954, the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education declared segregation in schools unconstitutional, Dallas, like many other cities throughout the South, still forced blacks to learn in inadequate, shabby buildings with outdated textbooks that white schools had already discarded.

One year after the Supreme Court ruling, nothing has changed and nothing will change for many years to come. It will not be until 1961, after receiving much pressure from federal courts, that the Dallas school board gradually begins desegregating schools by starting with the first grade alone. It will be then that eighteen black first graders enter a number of Dallas elementary schools that will have been all-white until then. Dallas’ public high schools will not begin any desegregation until 1967.

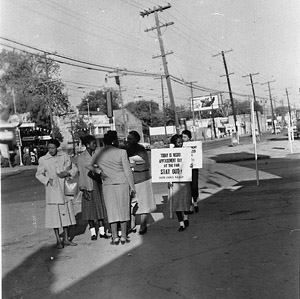

Dallas, like many other cities around the country in the 1950s, continues to enforce strict segregation laws. One of the most profound examples of segregation in Dallas is during the annual State Fair, when only one day is designated for blacks to attend. Named “Negro Achievement Day,” this poor attempt at hiding discrimination continues even after Fair Park authorities declared the State Fair “integrated” in 1953.

However, the integration still doesn’t apply to two attractions—“Laff in the Dark” and “Dodge ‘em Scooter”—because they involve “physical contact with white persons.” Outrage in the black community has arisen over the still-segregated State Fair, driving NAACP member Juanita Craft to start a boycott of Negro Appreciation Day, a boycott occurring at this moment during the 1955 State Fair of Texas. Not until many years from now will the State Fair fully integrate.

Finding a house to live in is another challenge in the Jim Crow world of 1955 Dallas. The often violent reactions of whites to earlier attempts to desegregate previously white neighborhoods has led leaders in the black community, with the active assistance of some of Dallas’ major white businessmen, to establish the all-black community known as Hamilton Park. When blacks bought homes that were located in heretofore white neighborhoods, chances were that either white families would immediately move away or the home of the black owner would sometimes be bombed or otherwise threatened. As a result of this harassment, Hamilton Park, much of it still under construction at its location out in the country east of Central Expressway near Forest Lane, is attracting black home buyers because of its seclusion and overall safety.

Jim Crow laws are exploited by department stores, restaurants, and movie theaters, and apply to public restrooms and water fountains, just to name a few. In order to prevent blacks from trying on clothes and “defiling” them, department stores ban blacks from shopping there as ordinary customers. One department store that has enforced this policy up to now is Neiman Marcus, despite Stanley Marcus’ disapproval. This same Stanley Marcus, CEO of Neiman Marcus, will soon change his store’s policies and will become a leader in Dallas’ desegregation movement.

Restaurants, like department stores, refuse service to blacks. In the 1950s, there is no such thing as a fast food chain or a drive-thru; people go into a restaurant and sit down to eat. The idea of sitting next to blacks at a lunch counter or near them at a dining table appalls some whites, contributing to their disdain for desegregation. Not until 1961 will blacks be able to sit beside whites at lunch counters in downtown Dallas.

Likewise, downtown’s Theatre Row—an area of numerous cinemas, including the Majestic Theatre and the Palace Theatre—do not sell tickets to blacks at the main entrance. The Majestic, which will be, almost sixty years later, the only remaining theatre from Theatre Row, and the Palace require blacks to sit in the balcony section, while whites sit in seats on the first floor.

Despite the obvious benefits of desegregating, prominent figures continue to voice their contempt for integration. In a Dallas Morning News article on August 20, 1955, Texas Attorney General John Ben Sheppard was quoted as saying, “I am of the very definite and firm opinion that the state laws of Texas still call for segregated schools. Our Texas laws were not passed on by the U.S. Supreme Court in the recent [segregation] cases, and until the Supreme Court specifically states otherwise, segregation remains the law in Texas.” In another article that will appear in the same newspaper on March 6, 1956, Reverend Earl Anderson of the Munger Place Baptist Church will be cited as exclaiming eight reasons why churches should not be integrated. Two of the eight radically distorted views of the Reverend are that “Negroes believe mixing races is disobedient to the word of God” and “One of the main policies of Communism is to mongrelize the human race.”

Transportation in Dallas, like that of Montgomery, Alabama, is strictly segregated due to Jim Crow laws. Despite attempts to remove “White” and “Colored” signs from railroads and bus terminals in early 1956, these signs will remain in Dallas for months, still enforcing segregated public transportation. However, in late April of 1956, the Dallas Transit Company will announce that all 530 of its buses will be desegregated and the “White” and “Colored” signs will be removed.

The Community Chest: An Incident at the Adolphus Hotel

Although the segregation due to Jim Crow laws continues to persist, more and more cracks are emerging in the structure of Jim Crow. An incident that occurred much earlier in the year is another example.

Arriving at the Adolphus Hotel in downtown Dallas in early 1955, a black man calmly walked toward the doorman at the front entrance. The doorman—unaware that the man he was facing was George Allen, a major black business executive in Dallas invited by white businessmen to serve on the board of the Community Chest, the city’s main fund-raising organization to benefit local community projects and a forerunner of the United Way—resolutely informed the businessman that blacks are not permitted in the lavish Adolphus Hotel.

Earnestly imploring the man to let him in, Allen explained that he was scheduled to attend a meeting of the Community Chest being held in the banquet room. The doorman, unconvinced, refused to let him pass by, taking him instead to the back of the building and telling him that he must enter through the delivery entrance. Determined to be treated equally and allowed in the front entrance, Allen rejected his instruction, walking instead across the street to a pay phone and contacting the chairman of the meeting himself to clear things up.

After the chairman, a white man, strode down to the entrance, Allen explained the predicament. The chairman, Fred Lange, embarrassed that Allen was being denied admittance into the hotel, asked the manager of the Adolphus to intervene and escort Allen through the front door like any other man. The manager did so.

Many years earlier, in 1939, the much younger Allen had applied to the University of Texas at Austin. Accepting his application, the all-white, segregated university had not realized he was black, so Allen went to his classes. After ten days, however, the college, finally recognizing that they had enrolled a black student, immediately rescinded his acceptance.

This same man—the man who just months ago was denied entrance through the front doors of the Adolphus until others intervened on his behalf—will become a prominent civic leader, working as a city councilman and a justice of the peace in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and a man whose legacy will be honored by having the Dallas County Courthouse named after him. It is this man, George Allen, whose son, Arthur, was one of two black students to enter Jesuit one month ago, in September 1955.

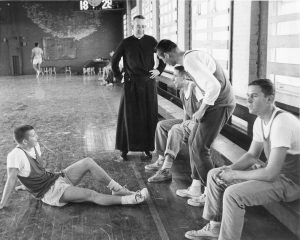

Intramurals: Fun and Games at Jesuit

Kenny Sargent slips in one more song before the commercials. Earth angel, earth angel will you be mine? My darling dear, love you all the time. The Penguins’ “Earth Angel” slowly plays as I park at Jesuit High School. Parking just across from the main entrance, I turn off the ignition and step out of my smooth Bel Air Coupe. After I hurriedly shut the car door, I run toward the entrance to meet a couple friends.

As we walk through the doorway, a sign in front of us reads, “BASKETBALL INTRAMURALS: FOURTH FLOOR.” My journey on this breezy Saturday morning is almost complete, the wide gray staircase ahead of us the only obstacle remaining. Worry-free and excited to play basketball, we are oblivious to the significance of two black students attending Jesuit, two students whose presence here will forever undermine the structure of Jim Crow in Dallas .

Looking Ahead to Part Three in the Series

The third and final part of this series will go back to the first week in September 1955, the week when two black students were admitted for the first time into an all-white high school in Dallas. Chronicling the experiences of their school years, the third part will reveal the various behind-the-scenes decisions, some potentially controversial, that led to the desegregation of Jesuit High School. Lastly, the lives of the two students during and after their time at Jesuit will be explained, uncovering the outdated Jim Crow way of life and proving that integration could work successfully, not only in Dallas, but in the entire United States.

1955: Jesuit High School and the Struggle for Civil Rights – A Three-Part Series

Sources for this series

“2 Negro Boys Registered by Jesuit School.” Dallas Morning News 3 Sept. 1955.

Allen, Arthur. “Arthur Allen’s Talk.” Jesuit College Prep, Dallas. 2006. Lecture.

Anderson, R. Bentley. “Black, White, and Catholic: Southern Jesuits Confront the Race Question, 1952.” The Catholic Historical Review 91.3 (2005): 484-506. ProQuest. Web. 27 Sept. 2006.

Anderson, R. Bentley. Black, White, and Catholic: New Orleans Interracialism, 1947-1956. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2005.

“Kenny Buddendorff, S.J.” Telephone interview. Dec. 2011.

“Color Line Declared Still Law in Texas.” Times Herald [Dallas] 20 Aug. 1955.

Bogen, Harvey. “Negro Group Plans Fair Gate Pickets.” Dallas Morning News 17 Oct. 1955.

Dallas Business Journal, ed. “Stanley Marcus, 1905-2002.” Dallas Business Journal (2002). Web. 8 Mar. 2007.

“Edmond, Charles.” Personal interview. December 2011.

“Jack Eifert.” Personal interview. Dec. 2011.

“Exploring the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial – The Washington Post.” Washington Post: Breaking News, World, US, DC News & Analysis. Ed. Kat Downs. 22 Aug. 2011. Web. Aug.-Sept. 2011. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/special/lifestyle/mlk2011/interactive-memorial/>.

Eyes on the Prize. Prod. Henry Hampton. PBS, 1987. DVD.

George, Charles. Life Under the Jim Crow Laws. 2000.

George Allen: An Oral History Interview. March 1981.

“Jerry Fagin, S.J.” Telephone interview. Dec. 2011.

Juanita Craft: An Oral History Interview. Dallas Public Library. 1979

Fowler, Wick. “Attorney Cites Edict of Court.” Times Herald [Dallas] 25 Apr. 1956.

Harper, Jack. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Hopp, James. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Killingsworth, Blake. “”Here I Am, Stuck in the Middle with You”: The Baptist Standard, Texas Baptist Leadership, and School Desegregation, 1954 to 1956.” Baptist History and Heritage (2006). Goliath Business News. Web. 8 Mar. 2007.

King, Martin Luther Jr. “I Have a Dream.” American Rhetoric: The Power of Oratory in the United States. Web. Sept. 2011. <http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkihaveadream.htm>.

Linden, Glenn M. Desegregating Schools in Dallas: Four Decades in the Federal Courts. 1995.

Murphy, Joseph. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

“McGowan, Richard, S.J.” Telephone interview. Dec. 2011.

Morehead, Richard M. “Integration Thus Far Affects Few in State.” Dallas Morning News 16 July 1955.

“Negroes Won’t Be Moved.” Times Herald [Dallas] 24 Apr. 1956.

“Pastor Calls for Help to Uphold Segregation.” Dallas Morning News 6 Mar. 1956.

Pettibone, Jerry. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Pitts, David. “Brown v. Board of Education: The Supreme Court Decision That Changed a Nation.” Issues of Democracy 4.2 (1999): 38-46. Web. Jan. 2012.

Raffetto, Francis P. “Negroes Ignore Fair Picketing.” Dallas Morning News 18 Oct. 1955.

Schack, William. “Neiman Marcus of Texas: Couture and Culture.” Commentary Magazine (1957).

“Segregation Signs Up Here Despite Order.” Times Herald [Dallas] 10 Jan. 1956.

Seymore, Kelly B. Times Herald [Dallas] 3 Apr. 1988.

Shields, Thomas J. Letter to Provincial. 14 Sept. 1955. MS. Dallas, TX.

Shields, Thomas J. Letter to Provincial. 31 Mar. 1955. MS. Dallas, TX.

Shipp, Bert. “School Integration Not Expected In Fall.” Times Herald [Dallas] 22 July 1956, sec. B. Print.

Stack, John. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Taliaferro, Mike. “Remembering Charles Edmond.” E-mail. Nov. 2011.

Williams, Juan. Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years, 1954-1965. 15th Anniversary ed. New York, NY: Penguin, 1987.