When learning about industrialization in World History class, I was most disappointed to see that one of the greatest engineering minds, and one of the most important people of the 20th century, had been rather casually glossed over, and not even mentioned once in any slides, or material. This person, was Isambard Kingdom Brunel, a British engineer who lived during the early to mid 19th century, who single handedly revolutionized both the railroad industry and the shipping industry, and achieved many firsts in engineering.

Early Life

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, was born on April 9th, 1806, on Britain Street in Portsmouth, England. His first and last name come from his father, Sir Marc Isambard Brunel, and his middle name stems from his mother, Sophia Kingdom. Marc Brunel was a French civil engineer, who took it upon himself to educate his son due to the family’s financial troubles. It is said that Isambard had learnt Euclidean Geometry by the age of eight, and was able to speak French and English fluently before he was even thirteen years old, and took a great interest in drawing buildings. At the age of eight, Isambard’s homeschooling ceased as his father chose to send him to a boarding school in Hove, a town in East Sussex, England. However, just six years later at age 14, his father sent him to be educated in France. First, he would be sent to the College of Caen, and then to the school; Lycée Henri-IV in Paris.

Unfortunately, just a year later, Isambard’s father was in severe debt, over £5,000, an outrageous sum of money at the time. For this, he would be sent to a Debtor’s Prison, and for three months he remained there, until he was offered employment by Tsar Alexander I of the Russian Empire, and in August of 1821, as the British government did not wish to lose such a prominent engineer, Marc would be released, and his debts cleared. Meanwhile, Isambard would complete his studies at Henri-IV in 1822, and Marc wished to send him to a French engineering school, but due to being an Englishman, Isambard would be denied entry, and instead he found himself being an apprentice for the clockmaker Abraham Louis Breguet, who was rather impressed with the young apprentice and praised his potential following Isambard’s return to England.

Engineering Career

Isambard’s first engineering project, would be when he worked as an assistant to his father on the Thames Tunnel project, which was a project to connect the London districts of Rotherhithe & Wapping via a tunnel underneath the River Thames. This would be the very first tunnel in the world to travel under a navigable river, and is still in use to this day for the London Underground. However, the work in constructing the tunnel was not easy, and several workers died during construction, and in once incident, two miners were killed, and Isambard was badly injured and required six months to recuperate. During this time, he began to create a design for a concept for a bridge in Bristol, and due to work stalling for several years on account of the danger and complexity of the project, Isambard would have no further involvement yet his father would complete the project.

In the 1830s, Isambard would begin rising to prominence. In 1831, Brunel would begin to design a bridge for Bristol, that being the Clifton Suspension Bridge. To design the bridge, a committee would be created to select the design, being headed by engineer Thomas Tedford, who rejected Isambard’s proposals at first, yet following public opposition, Isambard’s designs were selected. He would later write to his brother-in-law…

“Of all the wonderful feats I have performed, since I have been in this part of the world, I think yesterday I performed the most wonderful. I produced unanimity among 15 men who were all quarrelling about that most ticklish subject—taste”.

The Clifton Suspension Bridge, would be completed in 1864, five years after Isambard had died. The reason for such long construction, was due political riots caused by the British House of Lords rejecting a bill, which led to investors being driven away until 1862. At the time of its construction, it had the longest span of any bridge in the world. The bridge still stands, and millions of vehicles cross it every year.

His work on the Clifton Suspension Bridge certainly impressed many, as in 1833, Brunel would be appointed as the Chief Engineer of the newly formed ‘Great Western Railway’ (GWR), which is now remembered as being a symbol of industrialization. The GWR ran from London to Bristol, and would later run towards Exeter as well. As Chief Engineer, it appeared that Isambard had a tendency for radical ideas, such as making the decision to change the gauge of the railway, from ‘Standard Gauge’, to ‘Broad Gauge.’ Gauge is the width between two tracks. While this might not sound like much, changing gauges would mean that the GWR’s railway would be different from the entire United Kingdom, and would go against the standard practice that had been in use since the first railways in the world. Against what many believed at the time, would prove to be successful, as it allowed for more goods to be transported in less time, at a higher speed. From here, Isambard himself would essentially forge the entire railway, designing bridges, train stations, and creating the Box Tunnel, at the time the longest railway tunnel in the world. In his later life, Brunel would design ‘Paddington Station’ in London, one of the most iconic train stations in the world, and is of course, Paddington Bear’s namesake.

One of Isambard’s less successful and more radical ventures, was the “Atmospheric Caper”, which, rather than using powered engines, trains would be moved by being a vacuum that sucked air from a pipe, moving the train. This idea was a century ahead of its time, and although atmospheric railways were being experimented with by other engineers at the time, the sheer difficulty in maintenance, and the quick deterioration of the pipes needed, ended the project. Although now, modern atmospheric railways do exist, now that our modern technology overcomes the problems faced by Isambard.

Creating Modern Shipping

Back in 1833, when Isambard first became the Chief Engineer of the Great Western Railway, he had a radical idea, that a passenger in London should be able to travel from London, all the way to New York City in America on one ticket. Isambard believed that a passenger could take a GWR train to Bristol, then board a ship to America. This prompted the creation of the ‘Great Western Steamship Company.’ At the time, steamships were rather untested, mostly relegated to short routes between Ireland and Britain, or through the English Channel. In fact, many even feared the technology due to how unstable it was, to the point where even steamships still had rigged sails due to how frequently steam engines broke down. Furthermore, as all steamships were built for river transport or short range transport, it meant there were zero ships built for the purpose of crossing the Atlantic. This meant that Isambard, would need to make his own steamship, one that would create all modern shipping as we know it.

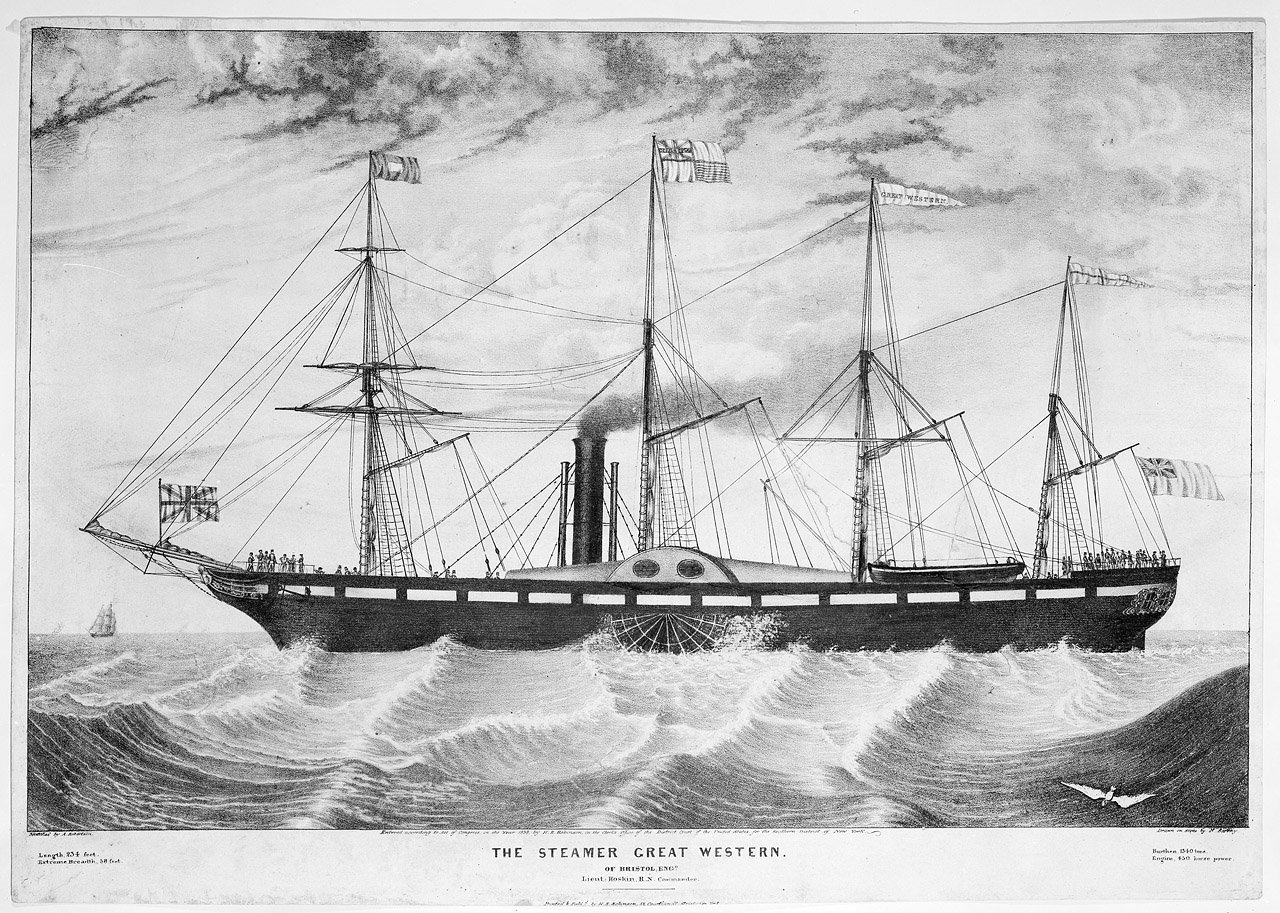

In 1838, Isambard would unveil his first ever steamship, the S.S. ‘Great Western.’ Great Western, was unlike any other ship in the world at the time, for she was the very first purpose-built oceanic steamship, and the largest ship in the world. All other steamships that had crossed the Atlantic were repurposed river steamers or island steamers, and while they could cross the Atlantic, they could only do so extremely slowly, and could not maintain a schedule due to how unreliable they were, and often switched to sail power when their engines inevitably broke down.

On April 8th, Great Western would depart Bristol for New York, yet Isambard could not attend, as a fire had injured him during construction of the ship, which delayed the ship’s voyage. This also meant, that Great Western would not be able to claim the title of being the first ship to cross the Atlantic solely under steam power, as another company had chartered a much smaller island steamer to try and compete with the Great Western. This ship, the ‘Sirius’ would depart Bristol four days before Great Western, and a race began between the two.

Although Sirius would arrive first in New York City and become the first ship to ever cross the Atlantic solely under steam power, she was out of coal, and her crew had to resort to burning furniture. Meanwhile a day later Great Western arrived at an even faster speed, with plenty of coal to spare. In other words, Great Western had proved to be the superior ship, and being the first purpose-built transoceanic steamship, she had begun a new age for shipping.

Just four years later, Isambard would build another steamship, the S.S. ‘Great Britain.’ Great Britain, would be even more revolutionary than the Great Western. In the years following the construction of the Great Western, Isambard began to believe that ships powered by propellers, were superior to those powered by paddle, as propellers could be easier to maintain, faster, and easier to construct. Furthermore, rather than be built from wood, Great Britain was built from iron, making her the first ever iron-hulled ship to have a propeller. For her innovation, Great Britain is referred to as being the first ocean liner in the world, and thanks to her, she kickstarted the age of ships that saw vessels like Titanic be constructed. If it were not for the Great Britain, modern shipping as we know it, would have certainly appeared different. Today, Great Britain is preserved as a museum ship in Bristol.

Isambard’s Final ‘Hurrah’

Following the success of his railways and steamships, in 1852, Isambard envisioned possibly one of, if not the most radical engineering idea of the century. He envisioned, a grand, five funneled ship with the ability to sail halfway around the world, non-stop, with the ability to carry passengers, cargo, animals, anything imaginable. He then began his greatest and final project, one that he loved dearly, the S.S. ‘Great Eastern.’

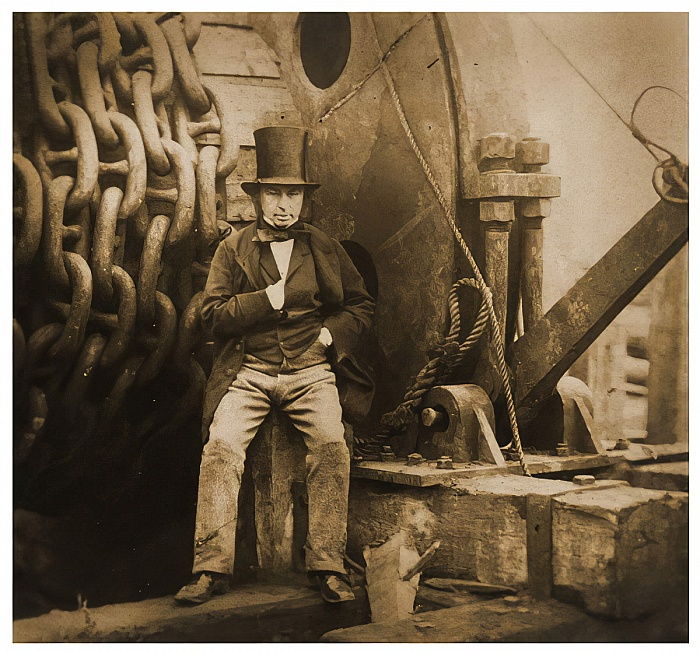

Isambard poured much effort into the construction of the Great Eastern, yet the project quickly ran overbudget, and began facing many technical problems, and many even made fun of it, and many believed a ship of such scale to be absolutely useless. In fact, two men would die in the construction, and several others injured. Isambard however, still chose to finish the ship no matter the cost, and on January 31st, 1858, Great Eastern would be launched. Isambard himself, appears to have worked alongside the common workers, and in virtually every photo, he is shown with dirty clothing, unkempt hair, showing his sheer dedication to the ship.

Great Eastern, would be over four times larger than any ship in the world at the time, carry five funnels, able to sail from Britain to Australia and back, had a double hull and double keel, could carry over 4,000 passengers, and at 692 feet long, and 18,915 tons, it was unrivaled, and was truly, the eighth wonder of the world.

Sadly, Isambard would never get to see his grandest, greatest project, be in service. Just days before the first sea trials of the ship in 1859, Isambard would stand on deck for a photo, only for him to collapse afterwards from a stroke, and a mere four days after the sea trials of the Great Eastern, Isambard would die on September 15th, 1859, aged 53.

Isambard, had poured his soul into the Great Eastern, loving it with all his heart, as if it was a daughter to him. He personally referred to the ship as his “Great Babe”, and would say about the ship:

“I have never embarked on any one thing to which I have so entirely devoted myself, and to which I have devoted so much time, thought and labour, on the success of which I have staked so much reputation.”

His greatest creation, the Great Eastern, would utterly fail as a passenger ship. Simply put, no port in the world was large enough to fit it, and it bankrupted its owners. This led to it being sold to become a ship that would lay telegraph cables, which it found success at, even laying the world’s first transatlantic telegraph cable. However, from here, it would live a life of depression, with there being no use for it. Its final form of service, would be a floating billboard, and following this, in 1889, it would be scrapped, never living up to what Isambard had dreamt of.

At 692 feet long, and 18,915 tons, no ship would ever be larger than it for the rest of the century, until the White Star Line (Who would later own R.M.S Titanic), constructed the ‘Celtic’ in 1901. Along with this, Great Eastern was able to carry over 4,000 passengers, a record that would stand unsurpassed until the German S.S. ‘Imperator’ of 1913, with 4,324 passengers, and even Imperator’s record would not be surpassed until the 21st century with modern cruise ships.

Legacy of Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Today, Isambard Kingdom Brunel is remembered as one of the greatest people to have ever lived in Britain, and a pioneer of industrialization, and the father of all modern shipping as we know it. Although not all of Isambard’s dreams were successful, he would always strive to achieve them no matter the cost, and very single creation of his, he loved dearly. If there is one thing that Isambard displays, it is to always, no matter what, to chase the best dreams you have.