Gentrification in Seoul: The Correlation Between Commercial and Residential Dynamics

Abstract

This literature review examines the phenomenon of gentrification in Seoul, South Korea, narrowing down on its impact on residential and commercial real markets, as well as population dynamics. Gentrification has been typically defined as the displacement of lower-income residents by higher-income households but has also been increasingly linked to current, broader urban transformations due to government policies and shifting demographics. In Seoul, rapid urbanization has exacerbated gentrification, especially in neighborhoods such as Yeonnam-dong and Itaewon. Synthesizing existing research and data, including information from both academic studies and local sources, this literature review explores the complex interactions between commercial and residential real estate markets. It highlights how rising property values in these areas correlate with declining local populations and increased commercial activity, leading to significant social and economic shifts. The concept of “degentrification,” relevant to Itaewon and regions where gentrification trends have begun to reverse due to economic pressures and external factors like the COVID-19 pandemic, has also been proportional to the analysis. The findings emphasize the need for integrated urban planning that considers both residential and commercial factors to mitigate gentrification’s detrimental effects. Despite its limitations, including reliance on primarily Korean data and potential biases, this review contributes to a deeper understanding of the gentrification process in Seoul, offering insights for sustainable urban development strategies that balance growth with the preservation of community diversity.

Keywords: Seoul, Gentrification, Urbanization, Commercialization, Residential Displacement,

- Introduction

The introduction will outline the concept of gentrification, its origins, and its significance in urban studies, particularly within Seoul, South Korea. The causes and consequences of gentrification will be briefly discussed, focusing on the correlation between residential and commercial real estate markets. Additionally, the scope of this study will be introduced, mentioning the specific districts of Seoul under examination and the key variables analyzed.

1.1. Background

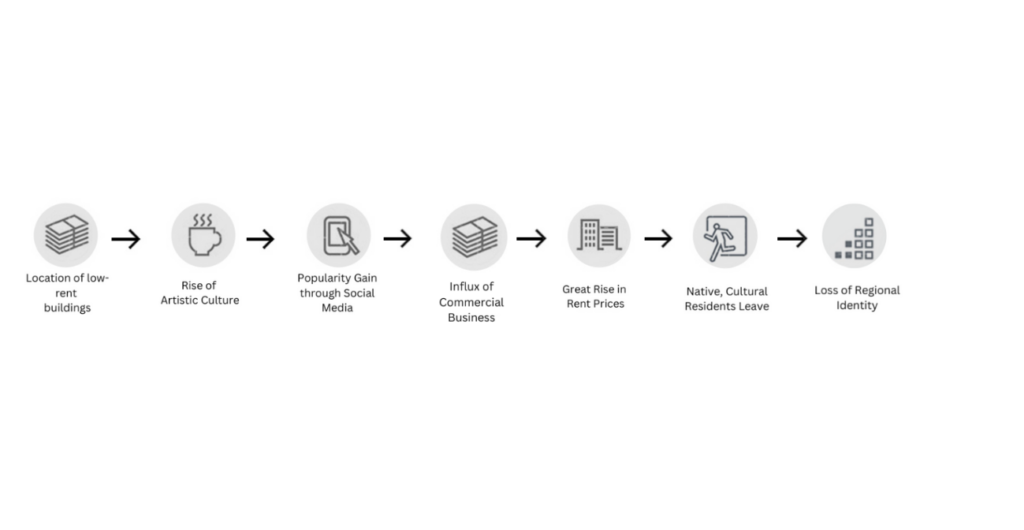

Gentrification, coined by sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964, referred to the changes in social structure and housing markets she observed in London’s inner city, where lower-income residents were displaced to make way for upper-class neighborhoods¹. Generally, gentrification is defined as the process in which lower-income households are displaced or replaced by higher-income households, but more recently, this definition has recently been used to describe changes in building use. Gentrification is being pointed out as a problem that reduces diversity in cities, with existing local businesses being replaced by upscale shops and restaurants that no longer meet the needs of local residents. Low-income residents become unable to afford to live in the area due to rising housing prices and are forced to move to other neighborhoods, a leading factor that increases social inequality. This inevitable social phenomenon appears to accelerate with the rapidly growing urbanization of Korea.

Why does gentrification occur? Gentrification typically stems from economic changes, which include increased investment in urban areas, rising property values, and an influx of wealthier residents. Consequently, a limited housing supply and increased demand can drive prices, pushing out long-term residents. Furthermore, government policies such as tax incentives and zoning regulations unintentionally promote gentrification, prioritizing redevelopment and disregarding affordable housing initiatives. However, most notably in Korea, the dynamic lifestyles of younger and affluent demographics increase demand for urban living and result in the transformation of neighborhoods that were previously considered undesirable.

Figure 1. Process of Gentrification

Standing apart from other urban centers, Korea’s largest city, Seoul, is home to about 15% of the nation’s population in a relatively small city². With Korea’s vast presence of mountains making up 70% of its geographical landscape, urban centers become more compact, where both commercial and residential buildings coincide in location³. Therefore, setting the stage for an already competitive housing market as well as growing commercial competition as a result of the constantly developing culture of Korea, gentrification has risen with fluctuations in demands for both residential and commercial purposes.

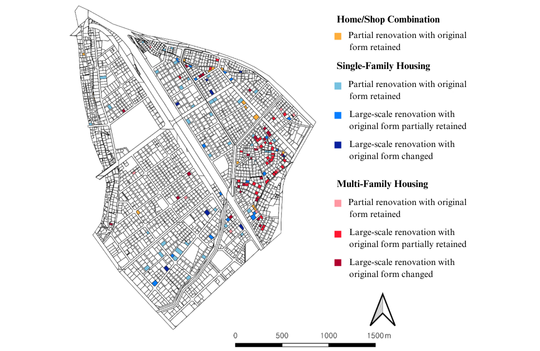

Figure 2. Distribution of buildings by renovation type, Yeonnam-Dong, Seoul

1.2 Study Focus

Although many gentrification studies primarily focus on either the geographical prevalence or price variable of gentrification, it becomes difficult to address how different trends recognize the correlation between these two. Over the past decades, most research emphasized the most notable indicator of gentrification, being the displacement effects and demographic shifts caused by rising rents and property prices, overlooking how commercial and residential real estate markets influence each other in gentrifying areas. To address these issues, this literature review explores how commercial and residential building prevalence correlates with the fluctuation of populations within Seoul, South Korea within the last 15 years. This paper utilizes a comprehensive analysis of previous research on commercial and residential buildings, combined with recent Korean real estate market data, to identify and visualize any direct correlations between these factors.

1.3 Study Scope

By examining these interactions, this review also aims to provide a more holistic view of how gentrification unfolds and the complicated impacts it has on urban environments. Seoul, the largest city in South Korea, ranks among the world’s top five urban areas based on population density⁴. Recent sustainability assessments place Seoul 11th among the cities with the highest potential for improvements in green space, population density, and renewable energy⁵. However, the city has been grappling with rampant sprawl due to urban development, redevelopment, and regeneration, which has inevitably led to gentrification. The study area is a mix of residential and commercial neighborhoods within key districts of Seoul that have either undergone or are undergoing gentrification. These districts include, but not are limited to, Yeon-nam Dong, Itaewon, Gangnam, and Hongdae.

1.4 Limitations and Contributions

The scope of this study excludes broader socio-economic factors such as income inequality and employment rates which are beyond the scope of this analysis. This broader approach aims to capture general trends but does not focus on specific, localized areas. The primary variables will be the number of both residential and commercial buildings within Seoul, as well as the mean price of each with time being used to measure change. One limitation is the reliance on primarily Korean data, also requiring official Korean government data. Such data, while authoritative, could potentially introduce biases as it may fabricate trends to align with governmental goals. Additionally, the study is confined to the last fifteen years, which may not fully capture longer-term trends and impacts of gentrification. The findings can significantly contribute to the field by highlighting the need for integrated urban planning and policy-making that considers both residential and commercial factors. By recognizing a correlation between the relationship of commercial and residential buildings, trends can be early recognized to prevent any negative consequences of gentrification, such as displacement and loss of cultural heritage. Through understanding these interactions, policymakers and urban planners can develop more balanced strategies that mitigate adverse impacts while fostering sustainable urban development.

- Methodology

The study area is a mix of residential and commercial neighborhoods within key districts of Seoul. These districts include, but not are limited to, Yeon-nam Dong, Itaewon, Gangnam, and Hongdae. Databases, such as Google Scholar, JSTOR, and Seoul Metropolitan Government’s Big Data Campus were used, along with keywords such as “gentrification in Seoul,” “urban development,” “residential displacement,” “commercial property trends,” and “socioeconomic impacts of gentrification.” Additionally, filters were applied to search only peer-reviewed articles, government reports, and reputable news sources to ensure reliability and relevance.

Most importantly, the studies needed to be directly related to the phenomenon of gentrification, including its impacts on both residential and commercial sectors with its effect on population dynamics. Both qualitative and quantitative studies were included to provide a balanced perspective on the topic.

In addition to peer-reviewed academic articles, Korean blogs were also incorporated into data collection. Often written by local residents, these blogs provide valuable perspectives that are sometimes overlooked in formal publications. Many of these blogs strengthen their credibility because of citations of official government sources. However, because a significant portion of this study was sourced from Korean materials, this required a more careful translation and interpretation to maintain the original implications.

Key details were extracted from each study, including the authors, publication date, research design, study location, key findings, and any statistical data related to property prices, vacancy rates, population changes, and commercial development. In particular, the extracted data focused on identifying correlations between the rise in property values, shifts in commercial activity, and changes in the residential population.

- Study of Gentrification in Seoul

Gentrification has been recognized and defined by Berry⁶ into 3 subcategories – Stage 1, Stage 2, and Stage 3. Stage 1 defines single or coupled households moving into low-income residential areas whilst benefiting the environment. Stage 2 is defined by the interest of the media and real estate agents, where native people start to face displacement problems. The final stage, stage 3, is where not only does the interest of media upsurge but so does that of the government, resulting in large surges in land price as well as large investments. These stages are highly relevant to the situation in Seoul, where rapid urbanization and development have accelerated the gentrification process.

3.1 Study of Yeonnam-Dong

Yeonnam-dong, once a residential area populated by lower to middle-class housing, faced the first stage of gentrification as the Hongdae commercial area began to expand its area in 2008⁶. However, since the opening of Gyeongui-seon Forest Road Park in 2015, Yeonnam-dong underwent all stages of gentrification. As existing residential buildings were refurbished as trendy commercial buildings, such as retail stores, pop-up stores, and restaurants, changes in the residential environment such as resident decline, commercialization, and changes in the use of buildings occurred.

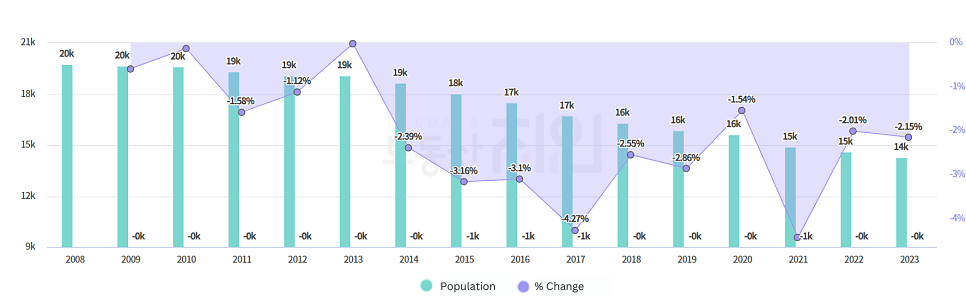

Figure 3. Demographic change of Yeonnam-dong, Seoul

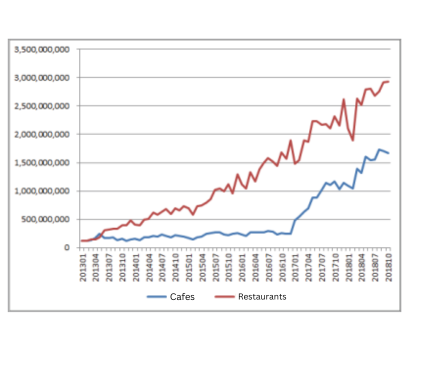

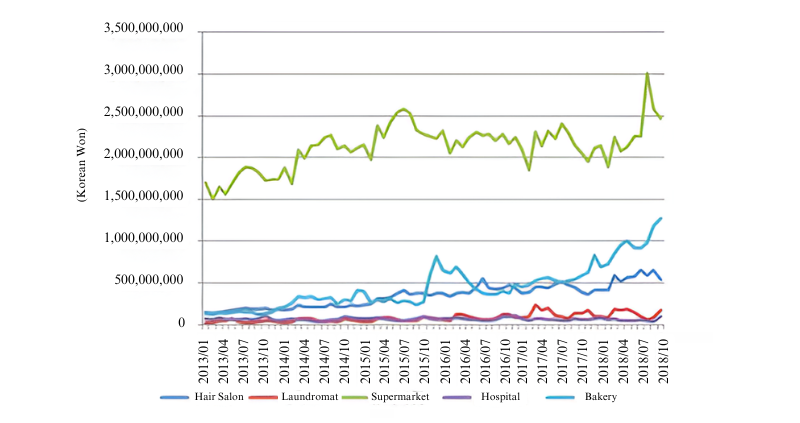

Figure 4. Estimated sales by industry in Yeonnam-dong (Western food, coffee and beverage)

Figure 5. Estimated Revenue by Lifestyle Industries

Yeonnam-dong and neighboring areas have experienced a population decline that has accelerated since 2015¹¹. The average annual sales growth rate of coffee beverages and western-style restaurants in Yunnan was 54.4% and 65.8%, respectively, a very steep increase. In particular, sales of coffee and beverages rose sharply from 2016 to 2017. On the other hand, the growth rate of sales in the living industry was relatively low. Beauty salons and dry cleaners increased, but supermarkets decreased by about 5.8% and general practitioners decreased. This decrease indicates that the number of existing inhabitants declined because supermarkets and general practitioners are catered to living residents. The decrease in sales of businesses that are mainly used by residents and the increase in businesses that are mainly used by visitors is a sign of commercial gentrification in residential areas.

Yeon-nam dong is a prime example of commercial gentrification – a concept branched out from Glass’ definition of gentrification and generally defined by the “boutiquing” of small retail stores in residential neighborhoods¹,⁷,⁸,⁹. Cultural consumption and movements for local rehabilitation in the neighborhoods typically lead to more cafés and shops. This ultimately leads to a higher volume of visitors and high-income immigrants, which substitute the stores for indigenous residents⁸,¹⁰. Upscale commercialization typically occurs in areas with lower property values, such as an area within a city that contains neighborhoods with low income¹⁰.

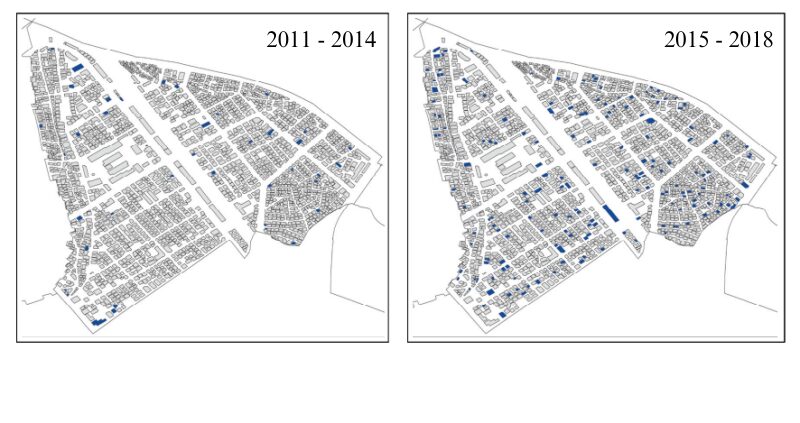

Figure 6. Locations of buildings licensed for 2 types of commercial facilities in Yeonnam-dong

As more licenses are approved for already pre-existing buildings, it can be assumed that the conversion of buildings is catered toward commercial use, ultimately diminishing the aggregate number of residential buildings. This single case study indicates a distinct relationship between commercial and residential development, similar to the balance of yin and yang. Gentrification in this context involves the renovation of already existing buildings rather than the construction of new ones, indicating that an increase in commercial buildings leads to a decrease in residential buildings.

To summarize, the population of Yeonnam-dong has steadily decreased but the number of floating populations has increased. Sales by industry in terms of sales by business type, the sales of living businesses mainly used by residents decreased while the sales of cafes and western-style restaurants, which are mainly used by visitors, increased sharply and have seen a sharp increase in sales. The most rapid changes occurred around the opening of Gyeongui-seon Forest Path Park in 2015¹¹.

The timing of the sharp changes in these indicators varies by one to two years, which is thought to be due to the time lag in the response of these indicators. In the case of house prices, it is generally the case that post-development housing prices generally start to rise before development and completion, reflecting expectations after development and completion. The inclusion of the period before the park opens reflects this tendency. When the park opens and the number of visitors increases, shops that cater to them will open, such as coffee and western restaurants, and a significant increase in visitors will lead to an increase in sales.

3.2 Study of Itaewon

Previous cities of Seoul follow patterns of gentrification similar to that of Yeonnam-dong. Since the 1960s, Itaewon, which developed into a foreign resident area with a stationed U.S. military base, began the phenomenon of gentrification in the 1980s. With the influx of artists, hipsters, and foreigners, Itaewon has been transformed into a multicultural street. The effects of gentrification have emerged, such as the replacement of low-income residents and the changing characteristics of the region.

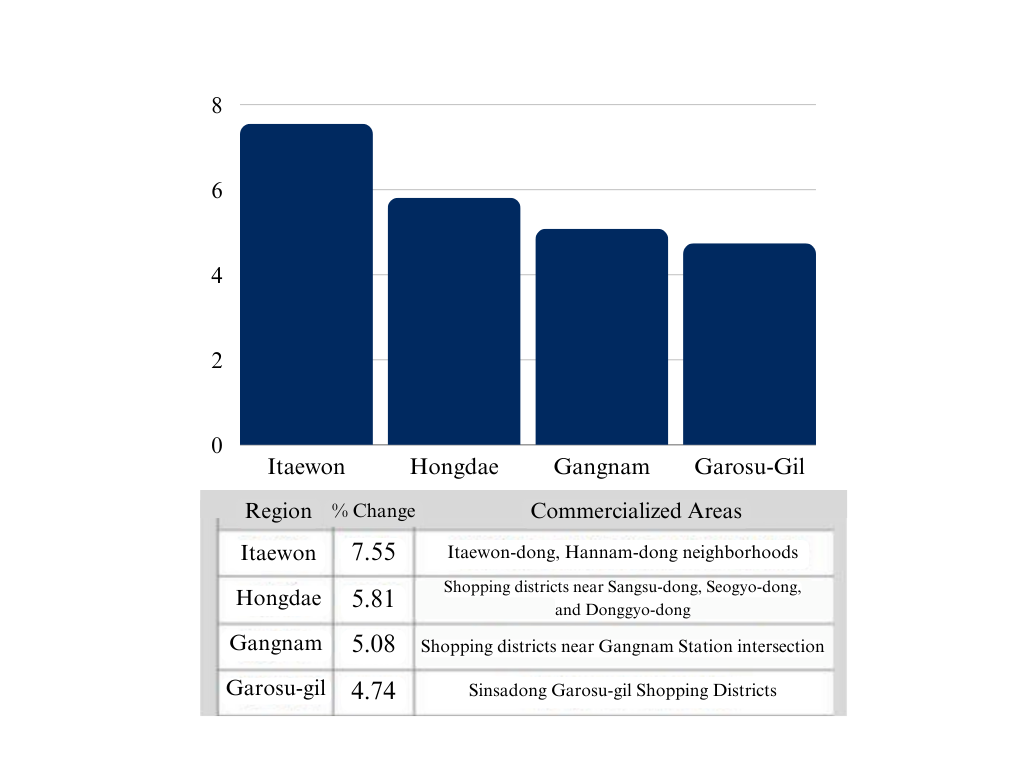

Figure 7. Rising land prices in major commercial districts in Seoul

According to the 2016 Standardized Land Price Index released by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport, land prices in Seoul’s Itaewon-dong and Hannam-dong neighborhoods rose 7.55% in 2016, nearly twice as much as the Seoul average (4.09%). The Hongdae shopping district near Sangsu-dong, Seogyo-dong, and Donggyo-dong also recorded a 5.81% increase, significantly higher than the Seoul average and the national average (4.47%). This was followed by the shopping districts near Gangnam Station intersection (5.08%) and Garosu-gil in Sinsa-dong (4.74%). These substantial increases in land prices highlight the broader trend of gentrification, where rising property values are often followed by displacement of long-term residents. As these areas become more commercially valuable, they also become less accessible to lower-income individuals.

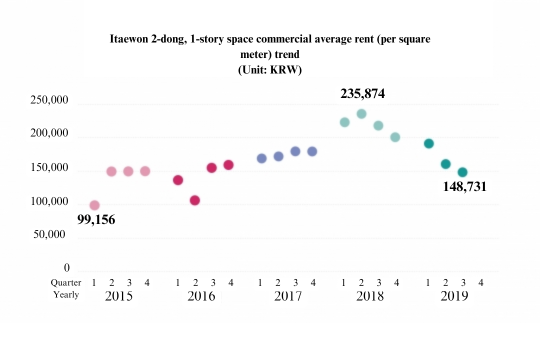

Figure 8. Changes in average rent (per square meter) for ground floor retail space in Itaewon 2-dong

In the third quarter of last year, the average rent for a ground-floor storefront on Hoenam-ro 13-gil soared from KRW 99,156 in the first quarter of 2015 to KRW 235,784 in the second quarter of 2018 per square meter (3.3 sq. ft.) and now stands at KRW 148,731. In 2016, Yongsan District selected 300 “world restaurants” in Yongsan District, including 39 restaurants in Gyeongridan-gil. However, by 2023, 34 of the 39 restaurants had closed¹². The closure or relocation of existing restaurants was largely due to the rapid rise of the commercial district and the skyrocketing rental prices.

Existing infrastructure has also been driven out by rent increases, and as the infrastructure for displaced residents dwindles, the actual landlords have also left the neighborhood. In fact, more than 50 percent of the registered properties in Yeolidan-gil were owned by outsiders¹³. When buildings that once housed families and long-term residents are converted into trendy cafes, boutiques, or short-term rental units, the neighborhood loses its residential character, which ultimately displaces existing residents and discourages new residents from moving in. Over time, Itaewon’s population density decreased.

However, a distinctive aspect, that sets it apart from Yeonnam-dong while supporting the broader analysis, is the phenomenon of “degentrification.” Smith’s¹⁴ observation of “a ruthless shakeout of small landlords, developers, marginal real estate agencies, and other gentrification-related businesses between 1989 and 1993” now is recognized as the term, “degentrification.” The first stage of degentrification (2018–2019) represents the maturation phase of gentrification, characterized by key themes such as “Legal System,” “Seoul,” and “Rental.” The second stage of degentrification (2019–June 30, 2020) corresponds with the COVID-19 pandemic, marked by prominent keywords like “Gentrification,” “COVID-19,” and “Demise.” Initially discovered in 2017, retail businesses and shops within Itaewon began to struggle with increasing rent trends¹⁵,¹⁶,¹⁷. More radically, after COVID-19, many more businesses were forced to close as a result of a sharp decline in tourism and foot traffic. Small business owners expressed contempt, claiming that government measures have detrimentally multiplied economic burdens¹⁸. Degentrification, however, is not necessarily a negative development. Previous inhabitants’ sense of belonging to the area may increase as commercialization begins to decrease, including those who were previously displaced. This can consequently lead to an increase in the local population as former residents return, including a lower cost of living because of reduced commercial pressure. Essentially, as gentrification progresses, the local population tends to diminish. Conversely, as degentrification takes place, the resident population often increases.

3.3 Additional Regions

Figure 9. Rents and Vacancy Rates by Major Commercial Districts (Based on medium and large retail centers)

To highlight the widespread pattern of population shifts and gentrification across Korea, When comparing the data from 2019 and 2023, Myeongdong, Gangnam, Hongdae, and Apgujeong-dong’s Garosu-gil have decreased in rent and increased in vacancy rate, while Seongsu-dong, Dosan-daero, and Hannam-dong have increased in rent and decreased in vacancy rate. Garosu-gil, Myeongdong, Gangnam, and Hongdae show the end of gentrification, while Seongsu-dong Guadosan-daero and Hannam-dong show the beginning of gentrification. As these areas become more commercialized, the original residential population decreases, and the higher vacancy rates indicate a potential decline in demand, leading to fewer residents.

- Discussion and Conclusion

This study set out to examine the characteristics of commercial and residential building prices and prevalence within the context of gentrification in Seoul, particularly Yeonnam-dong and Itaewon. The findings revealed similar trends, where an increase in property values correlates with a significant decline in the local population. The comparative analysis of Yeonnam-dong and Itaewon reveals broader trends in urban development across Seoul. Neighborhoods such as Yeonnam-dong and Itaewon saw a predictable pattern of gentrification: the influx of wealthier residents led to rising property values, the displacement of original inhabitants, and the transformation of residential spaces into commercial ones.

How does this rapid change in neighborhoods such as Itaewon and Yeonnam-dong affect residents? Gentrification in residential areas is not just a problem for commercial tenants but is fundamentally related to the housing problems of local residents. Unlike the large-scale demolitions caused by maintenance projects in the past, displacement due to gentrification occurs on a small scale at the individual household level (Kim, Da-yoon, et al., 2017) and is relatively difficult to capture because it tends to be dismissed as an economic problem of households that cannot afford rising rents. In particular, residential areas dominated by single-family, multi-family, and row houses, such as Yeonnam-dong, are home to urban residents with relatively low housing affordability, so the occurrence of gentrification in these areas can be even more burdensome for renters. Additionally, recent trends indicate that retailers are encroaching into residential neighborhoods. Gentrification is often caused by the infiltration of shops into residential areas, so it is necessary to continue to pay attention to and study the changes and impacts of residential areas. Furthermore, changes in the residential environment in more qualitative aspects, such as changes in the quality of life and satisfaction with the residential environment due to changes in the class of residents and the decrease in residential buildings and the increase in commercial buildings, should be studied.

Gentrification and new urbanization are similar concepts related to urban development, but gentrification is the creation of new cities in existing urban areas, while new urbanization is the creation of new cities, usually in the outskirts of cities or in rural areas. Gentrification is typically fueled by private companies or individuals, whereas new urbanization is often caused by national or local governments. While gentrification focuses on revitalizing and developing existing areas, new urbanization aims to distribute the population more evenly with less disruption to the residential population Unlike gentrification, which often results in the displacement of residents as property values rise, new urbanization involves the creation of entirely new urban areas, often being the outskirts or open areas of existing cities. This expansion is driven by government initiatives to reduce pressure on already existing urban centers, preventing overcrowding and soaring property prices.

One of the many solutions to decrease gentrification is for governments to implement policies that control the price of housing so that low-income residents can afford to buy, preserving affordable housing stock and providing support to vulnerable residents facing displacement. One solution, rent stabilization, is when the government enforces settlements that limit rent growth and protect tenants’ rights. Support for low-income residents provides financial assistance to help low-income residents buy or rent a home. Another solution could be to maintain neighborhood diversity through mixed-income developments that allow low-income and high-income residents to live together, and create systems that allow local residents to participate and voice their opinions in the urban development planning process. It is important to keep in mind that steeply increasing rents for temporary financial gains by landlords can lead to a downward spiral of the entire surrounding commercial district and lead to local decline rather than local development

Although this study becomes limited by its reliance on data primarily sourced from Korea, including official government statistics as well as news articles, inviting the potential for bias, these provide a valuable perspective on the patterns and impacts of gentrification within the specific context of Seoul. Gentrification is undoubtedly a complex issue that creates tension between urban development and conflict, but it requires ongoing efforts to minimize its negative effects and maintain the diversity of the city. As Seoul continues to grow and modernize, it is crucial for policymakers, urban planners, and communities to work collaboratively to ensure that development is inclusive, sustainable, and mindful of the needs of all residents who call their neighborhood home.

- References

- Glass, R. London: Aspects of change. The Gentrification Reader; Routledge: London, UK, New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780415548397

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. “Population of Seoul Korea |.” Official Website of The, 2022, english.seoul.go.kr/seoul-views/meaning-of-seoul/4-population/.

- “Physical Setting of Korea.” Ngii.go.kr, 2014, nationalatlas.ngii.go.kr/pages/page_1270.php#:~:text=Although%20approximately%2070%25%20of%20Korea%27s.

- Galea, S.; Ettman, C.K.; Vlahov, D. The Present and future of cities. In Urban Health; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; p. 1.

- Phillis, Y.A.; Kouikoglou, V.S.; Verdugo, C. Urban sustainability assessment and ranking of cities. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2017, 64, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.S. A Study on Regional Preference Factors of Creative Class: Focusing on the Creative Milieu Characteristics of Yeonnam-dong. Ph.D. Thesis; Seoul National University: Seoul, Korea, 2014; pp. 86-91

- Doucet, B. A Process of Change and a Changing Process: Introduction to the Special Issue on Contemporary Gentrification. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2014, 105, 125-139.

- Zukin, S.; Trujillo, V.; Frase, P.; Jackson, D.; Recuber, T.; Walker, A. New retail capital and neighborhood change: Boutiques and gentrification in New York City. City Community 2009, 8, 47-64.

- Cheshire, P. Why do birds of a feather flock together? Social mix and social welfare: A quantitative appraisal. Mix. Communities Gentrification Stealth 2011, 17-24.

- Burnett, K. Commodifying poverty: Gentrification and consumption in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Urban Geogr. 2014, 35, 157-176.

- An, Dai Whan, and Jae-Young Lee. “Implications of Renovated Buildings in Yeonnam-Dong, Seoul, an Area under Commercial Gentrification.” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 3, 19 Jan. 2023, p. 1960, https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031960.

- 네이버헤럴드경제 . “다 떠난 경리단길…“맛집” 39곳 중 5곳만 남았다[서울, 젠트리피케이 션에 바래다].” Naver.com, 2020, n.news.naver.com/mnews/article/016/0001668563.

- 네이버헤럴드경제 . “다 떠난 경리단길…“맛집” 39곳 중 5곳만 남았다[서울, 젠트리피케이션에 바래다].” Naver.com, 2020, n.news.naver.com/mnews/article/016/0001668563.

- Smith, N. 1954–2012 Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space; 3rd ed. Book collections on Project MUSE University of Georgia Press: Athens, Greece, 2008; ISBN 978-0-8203-3590-2

- Gentrification, USFK Relocation Kill Itaewon. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/biz/2021/09/488_277093.html

- Ji-hye, S. [Weekender] Itaewon’s Identity Wanes in the Wake of Gentrification. Available online: http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20190314000295

- Han, Soyoung, et al. “Degentrification? Different Aspects of Gentrification before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Land, vol. 10, no. 11, 11 Nov. 2021, p. 1234, https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111234.

- Lee, H. Myeong-dong is Also Sluggish.. The Limit of Self-Employed People from Gentrification to COVID-19. Available online: http://www.newspost.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=90283