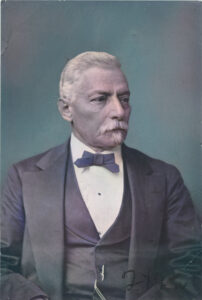

Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard, the “Hero of Fort Sumter” and companion of Robert E. Lee, engaged in support of civil rights for Black Louisianans after the conclusion of the Civil War. However, Beauregard’s true intentions behind supporting such a revolutionary cause for the time period is open to debate.

Heritage and War

Originating from the Casta system established in the eighteenth century during Spain’s reign over the Americas, the term “Creole” refers to those of mixed European and Black descent or a person of European descent born in the Americas.

The Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard belonged to this vast ethnic group. He was a French Creole whose parents were of both French and Welsh ancestry, and through his mother held connections to the House of Este, a historic Italian noble family that ruled the Duchy of Ferrara, which later became the Duchy of Moderna and Reggio.

Beauregard possessed a unique French and Welsh ancestry, his Catholic faith – a religion widely frowned upon in the South during this period because of its Baptist majority – as well as connection to North Italian nobility rather than being descendants of the Anglo planter gentry (e.g. Robert E. Lee). Due to not sharing traits with the Southern elite, Beauregard was widely ostracized by Confederate senior officials and generals, many of whom he met at West Point and during the Mexican War. For instance, Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, greatly interfered with Beauregard’s strategic planning throughout the Civil War, arguably preventing many Southern victories such as the capture of Washington D.C.

During the conflict, he was widely respected by those under his command, a Confederate soldier serving under Beauregard stating in a letter to his father that they “love that little black Frenchman, [and] there is not a man in the army who wouldn’t willingly die in following his lead.”

Beauregard included a black man in his entourage, South Carolinian Frederick Maginnis, to whom Beauregard confided in, discussing with him his intricate war plans while encamped near the battlefield. Following the end of the war, Maginnis became a close companion of ex-Confederate President Jefferson Davis with whom he met during the conflict.

Maginnis told the Baltimore Sun newspaper, “I first saw Mr. Davis in front of General Beauregard’s tent during the battle of Manassas. I had no idea at the time who he was, but I knew from the dignity of his bearing that he was a man of prominence.”

Return to New Orleans

Upon the war’s conclusion, Beauregard returned to his native Louisiana, traveling from Durham, North Carolina where he and General Joseph E. Johnston had surrendered to Union General Sherman on April 26, 1865.

Counseled by Lee and Johnston, Beauregard swore an oath of loyalty to the Union before Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler, the Union Military Governor of New Orleans, on September 16, 1865, and was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson on July 4, 1868.

A month following his oath of loyalty, Beauregard acquired the position of chief engineer of the New Orleans, Jackson, and Great Northern Railroad, holding this position until 1870 when the company was taken over and he was made president of the New Orleans and Carrollton Street Railway, his military prowess granting him high paying jobs in the civilian sector.

Beauregard later lost this job and was recruited as a supervisor to the Louisiana Lottery Company along with former Confederate General Jubal Early, making public appearances that furthered the company’s respectability.

During the Reconstruction Period, previous supporters of the Confederacy were not allowed to hold public office or to vote, leading them to become dependent upon the newly installed Radical Republican government for monetary and legal relief until the end of the Reconstruction period in Louisiana in 1877. The lottery was an attempt by desperate Southerners who had been disenfranchised by Union authorities to win funds in order to regain their lives or to leave the state and settle outside of the effects of the Reconstruction.

Postbellum Politics

Beauregard’s popularity in the postbellum South allowed him to maintain a stable income despite losing his position in the railroad, dissimilar to the destitution faced by other ex-Confederates during this period. This allowed for him to plan a method by which Reconstruction would be defeated in his native Louisiana.

In 1872, Beauregard resumed interest in politics in Louisiana where he would make his most significant contribution to the Reconstruction story.

A new party appeared in Louisiana called the Reform Party. With Beauregard as the cornerstone, the Reform Party consisted of conservative businessmen that advocated economical state government and recognition of the civil and political rights of Black Americans.

In doing this, he advised the forgetting of old issues, with the Union of Conservatives to remove the corruption and extravagance of the Reconstruction. The South objected to the Reconstruction government’s installment because it sought to remove judges and public officials who had supported secession from the representation of their own peoples’ beliefs in state politics.

In the following year, the Reform Party was renamed to the “Louisiana Unification Movement” to better represent its plan to create a political union between the races of Louisiana during a time of heightened racial tension. The platform of the party combined with the leaders of the New Orleans business sector and wealthy Black American sponsors, “Creoles of Color,” who had been free before the war.

The purpose of the movement was to solve the issue of carpetbag government forced upon the Southern people. The platform also denounced discrimination because of color in hiring laborers and called for the abandonment of racial segregation in public spaces such as schools and railroads. The plan further called for Black Americans to join in solidarity with Anglo Southerners in the ousting of the Radical Republican government. However, it was at a mass meeting held on June 16, 1873 that spelled the demise of the Louisiana Unification Movement.

“I am persuaded that the natural relation between the white and colored people is that of friendship, I am persuaded that their interests are identical; that their destinies in this state, where the two races are linked together, and that there is no prosperity in Louisiana that must not be the result of their cooperation.” – P. G. T. Beauregard

These promises of equality were not believed by the black Creole business owners present at this assembly as recorded in Harry Williams’s The Louisiana Unification Movement of 1873 published by the Southern Historical Association in 1945.

Through many wealthy Creoles of Color in Louisiana were former slave-holders themselves, they believed the Louisiana Unification Movement to be attempting to transform them as well as the large African American population of the state into political pawns in an attempt to depose of the Radical Republicans in the Louisiana state government, which raises the question: Was Beauregard truly genuine in his pursuit for the civil rights of Black Louisianans?

The matter of Radical Republican rule was finally resolved when President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew federal troops from the South following his election in 1876, subsequently ending Radical Republican rule in Louisiana. The end of Reconstruction and the removal of Federal troops from the South brought about the return of Democratic party control, thereby placing politicians who did not support the advancing of Black Southerners in political office.

The renaissance of Democratic Party control after the Reconstruction led to the enacting of the Jim Crow laws that sought to disenfranchise newly empowered politicians of color, with these laws remaining in effect until the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century.