“America’s ground forces will have to be prepared to perform the tasks Caesar assigned to his Legions – win wars, restore order, and preserve a stable and prosperous peace… wherever direct American influence is required.”

The preceding quote was written in 1997 by veteran U.S. Army Colonel Douglas A. MacGregor, who wrote the groundbreaking book Breaking the Phalanx: A New Design for Land-Power in the 21st Century, in which he recommended a radical restructuring of the U.S ground forces to meet the unconventional threats of the future.

This article – the first in a two-part series regarding American power projection in the 21st Century – will review and analyze Colonel MacGregor’s military science book, and compare it to current and past American conflicts for the past 24 years. Was the decentralization of the American military, especially its ground forces, necessary? How did our adversaries fight compared to this new century of warfighting? And will MacGregor’s model of “breaking the phalanx” hold up in the future?

These questions will be answered below, and my next article in the series will cover the last question – namely in the form of my own recommendation for US power projection for the 2020s and 2030s.

![DVIDS - Images - Combined Arms Rehearsal in preparation for Exercise Allied Spirit [Image 2 of 4]](https://d1ldvf68ux039x.cloudfront.net/thumbs/photos/2006/6236177/1000w_q95.jpg)

A Review of Previous American Ground Operations in the 20th Century

During the Second World War, the US Armed Forces transformed into being the world’s greatest military. Embodying excellence in logistics and organizational management, the American military further expanded into experimentation with combined arms warfare, where a military will utilize all aspects of its available armed forces to achieve mutually complementary effects.

For example, the American military employed effective fire control systems, such as artillery or close air support, to augment its ground forces in their attacks on enemy positions. The infantry were trained to work alongside armored or mechanized forces while coordinating movements with available fire support. The result was that on the tactical level, American ground forces were more than a match for their German, Italian, or Japanese opponents.

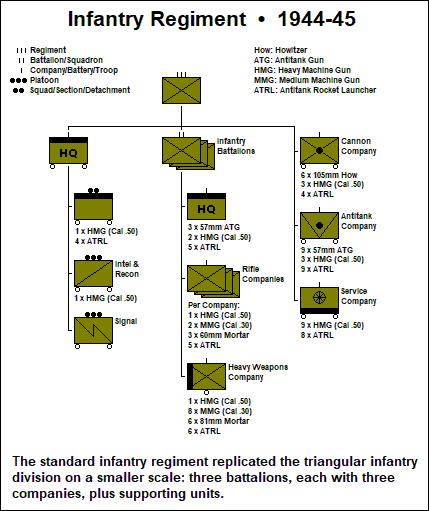

This level of coordination – as well as the mobilization of millions of Americans for armed service – necessitated truly massive ground formations. The smallest ground unit available to a commander is a squad, formed of usually 9 to 10 men. Squads form platoons, commanded by a lieutenant, and platoons form companies, commanded by a captain. Companies form battalions, and battalions form regiments and regiments form divisions. Divisions in WW2 were usually comprised of up to 15,000 personnel, with more personnel for Marine Amphibious Assault Divisions.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/4BFJMYAOPNBW3K4DDGYIG7B67U.jpg)

Divisions coalesced into corps, usually comprised of up to four to five divisions, and two or three corps formed into an Army. In the European Theater, the U.S Army fielded six armies, totaling nearly half a million frontline ground troops. Another 2 million were assigned as rear-echelon support for logistics, training, and transportation roles. As a result, a colossal menace had been created, necessary for long, attritional battles against similarly organized enemy forces.

Although the division was the heart of American ground forces, commanders began to experiment with Regimental Combat Teams or RCTs, essentially groupings of a few thousand personnel created for a specific task that could be quickly dispatched if necessary. Korea saw RCTs deployed with more frequency as the rough terrain necessitated smaller groupings of soldiers and Marines to more rapidly respond to threats.

Vietnam, with its harsh tropical terrain, hostile population, and an asymmetric enemy that blended with local civilian population centers, saw fewer instances where an entire American division was deployed in a centralized area for prolonged ground operations. It was only when the North Vietnamese Army or Viet Cong fought conventionally – with direct attacks on American positions to hold terrain – did the US Army reorganized its formations to directly repel enemy attacks.

Conflicts through the Caribbean were too small to deploy large formations, and so the American military utilized its smaller and more agile units, such as the airborne, 75th Ranger Regiment, and special forces, to deal with threats. But the invasion of Kuwait by Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi Army necessitated a different response.

The US ground forces consisted of three corps-sized formations, with nearly 950,000 total Coalition troops participating in the liberation of Kuwait from Iraqi forces. The campaign was a decisive American success but saw formerly more mobile and decentralized commands, such as the 101st Airborne or Marine Divisions, become as bloated as their Army counterparts.

Colonel Douglas MacGregor, a graduate of West Point and a member of the US Army served as an operations staff officer in the 4th Cavalry Regiment. He participated in the decisive battle for 73 Easting. This battle lasted 30 minutes where American tanks destroyed 160 Iraqi tanks, and 180 infantry fighting vehicles, killed a thousand Iraqis, and captured a thousand more. In the end, the Americans had minimal losses of about two dozen killed and a single armored fighting vehicle damaged.

MacGregor, after analyzing the decisive results of Desert Storm, worked in numerous war games as an armored officer and concluded that while the traditional structure of U.S ground forces had easily obliterated the conventional Iraqi army, he argued in Breaking the Phalanx that a “joint military structure” was needed that would essentially decentralize the armed forces to make it easier to respond to threats.

“Desert Storm demonstrated for the first time, really, that American land-based air and rapidly deployable Army heavy ground forces are global weapons like the legions of the ancient world.” – Colonel MacGregor

Colonel MacGregor’s Recommendations for Future US Power Projection

MacGregor believed that American power projection relied on its ground forces to not only fight the enemy, but to subjugate, coerce, and cooperate with local populations wherever necessary.

To better support this goal, he recommended that America decentralize and break apart its ground forces, to depart from the era of corps and divisions, where tens of thousands of soldiers coalesced into massive structures that required complex logistics, sustainment, and communications, and towards a new era of smaller, flexible units that could deploy rapidly to combat zones.

MacGregor compares the rigid, inflexible Greek phalanx to the flexible Roman maniple, the latter enabling Rome to conquer the Mediterranean. MacGregor gives the following assessment of the two diametrically opposed organization’s structures:

“When the two armies collided in battle, the Macedonian right wing drove back the

Roman left, but while the Macedonian left was deploying from march column on uneven ground, it was struck in the flank and routed by the Roman right. Part of the advancing Roman right suddenly swung around—apparently without orders—hitting the Macedonian right wing and driving it from the field in confusion.

Macedonian losses were about 13,000; Roman, a few hundred. Without the means to continue the war, the Macedonians renounced all claims to Greece and the Aegean coast. Rome’s victory made Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean an integral part of the Roman Empire for half a millennium. And the Phalanx, the backbone of the Macedonian military system, was broken.”

The apparently “orderless” maneuver by the Roman maniple was not so chaotic as it may seem – it was all due to one Roman junior officer, a centurion (the equivalent of a company commander in today’s armed forces) who elected to maneuver his force to attack the Greeks from the rear, winning the battle. The fate of Greece – and much of the Mediterranean – was decided by a single Roman officer who made a split section at the crucial moment of battle.

MacGregor viewed such decisions as necessary for future American ground operations. To a large extent, decentralized leadership has been a staple of American warfighting since WW2. A strong, independent, and experienced non-commissioned officer (NCO) corps, who are the higher ranked enlisted personnel who while still being subordinate to even the lowest ranked officer, have such extensive experience they are often relied upon to manage troops to assist officers.

For example, if an officer is killed or wounded, the next in charge usually is an NCO. NCOs in infantry units are integral to managing training, supply, and logistics. They are the intermediary between the officers and the individual privates and corporals. Often they are used to command smaller units of personnel required for duties that an officer cannot be spared for. They are the backbone of the American professional military.

But MacGregor viewed decentralization as an inevitable product of the “increasing proliferation of lethal weaponry,” necessitating a “command, control, and sustainment of dispersed formations [which] increases reliance on subordinate officers’ and soldiers’ judgment, intelligence and character.”

To achieve these results, MacGregor idealized an Army in which “operational changes that capitalize on these human qualities,” which would “work to the benefit of armies with high-quality manpower [which would] encourage initiative and develop more flexible and adaptive fighting formations.”

![DVIDS - Images - Fort McCoy NCO Academy operations in May 2022 [Image 1 of 9]](https://d1ldvf68ux039x.cloudfront.net/thumbs/photos/2206/7247785/2000w_q95.jpg)

MacGregor believed that “land power will be an essential feature of statecraft and deterrence. Today, historians remind Americans that the refusal of the United States and Great Britain to maintain armies capable of presenting real resistance to fascism on the Eurasian landmass was an important source of encouragement to the aggressors, who concluded that they could achieve their aims without American interference even though America possessed enormous sea- and airpower.”

MacGregor believed an over-fixation on “high tech” equipment that shrank the deployable size of America’s armed forces would “forfeit military flexibility and courts strategic irrelevance in the 21st century,” by focusing too much on “ships, planes, and missiles.”

At the end of the day, even if an military bombs the enemy to bits, and blockade their country, the military will still need to send in well-trained, disciplined, supplied, and led infantry to capture, hold, and secure ground positions.

Such an analysis falls in line with past American military practices. After WW2, the US Army’s budget was slashed, and while the structure of divisions and corps was maintained, the personnel who staffed said structures were cut in number. Instead, the US Air Force – with its possession of nuclear weapons – was given most of the funding, as the Department of Defense believed that nukes were not only cheaper but also more effective at deterring a communist invasion of Europe.

The result was an ineffective and poorly funded US Army that, when faced with numerous ground conflicts throughout the 1950s and 60s, was simply not prepared to achieve desired goals as easily as they had done in the Second World War.

MacGregor advocated in summary that there ought to be “an adoption of a flexible brigade-based division structure that can be tailored to specific missions.”

For training and maintaining such formations, MacGregor desired:

“setting up three six-month operational readiness cycles through which units continuously rotate during peacetime – a ‘training cycle,’ which prepares units for deployment, a ‘deployment-ready cycle,’ which sustains units at their highest readiness in preparation for real-world contingencies, and a ‘reconstitution cycle,’ which replenishes units in preparation for starting the entire process all over again.”

MacGregor believed that while the Navy and Air Force still were necessary in US power projection, the usage of Carrier Battle Groups (CVBG’s) represented an unnecessary drain on the US defense budget and was less effective than traditional American ground forces. The proliferation of lethal weapons systems, as mentioned above, made carriers irrelevant because they could be easily sunk by cruise missiles, drones, or other cheaper systems.

Did MacGregor’s Analysis Hold Up?

Just four years after Breaking the Phalanx was published, the U.S. was under attack by terrorism and soon invaded Afghanistan and Iraq. Both conflicts were initially primarily land-based, with Iraq in particular seeing the US and Coalition forces invading through the use of large, conventional ground formations to seize territory.

Afghanistan, with its rugged terrain, saw smaller dispersions of American formations, supported by air and naval power. Iraq, now occupied by Coalition forces, saw local instances of militant groups resisting the Coalition presence, and the outbreak of civil war created instability throughout the region.

MacGregor – who advised the US Army throughout its invasion – saw his suggestions of a more decentralized yet still increasingly prominent US Army partially come to fruition. For most of the Bush administration, the US Army and Marine Corps maintained large ground formations in Iraq and Afghanistan, with the Navy and Air Force being relegated to the sidelines. Both the Army and Marines saw the traditional division structure be dissolved into a new system of brigade combat teams, smaller-sized formations that could be tailored to a specific mission profile, take charge.

But in 2004 MacGregor retired from the Army, and in 2009 the newly elected Obama administration switched up American strategy. Obama, seeking to reduce American casualties, gave the controls to the Air Force and Navy who employed the usage of drones to strike enemy targets. Throughout the 2010s, although America maintained tens of thousands of personnel throughout the Middle East, very few of them were frontline personnel. Drone strikes were the new method to reduce Islamic terrorism throughout the region.

MacGregor’s push to reduce funding for the US Navy’s carrier groups never reached fruition either. His focus on a more land-focused American military was sidelined as the US Navy began to introduce a new model of nuclear-powered carriers and the deployment of the multi-variable F-35 meant that the Navy once again became the military’s favorite sibling.

Moreover, in my opinion, MacGregor’s hostility towards a truly massive and multi-domain Navy was misplaced. The Navy’s use of aircraft carriers offers the US an effective power projection model that saves American lives, even if it is more costly. Recent drone, missile, and manned aircraft strikes against Houthi terrorist targets in Yemen prove the flexibility and feasibility of naval power projection. According to MacGregor’s model, a response to Houthi aggression in Yemen would be to send in ground strike groups to neutralize local threats.

This however opens American forces up to the risk of entanglements in foreign nations that would not be happy to see American tanks parked in their cities. Ground forces are not “whack-a-moles” that can be quickly inserted in, destroy targets, and leave. They require logistics and sustainment that keep them rather immobile and attract hostility from local populations.

Ironically, the usage of special forces such as Navy SEALS, Green Berets, Rangers, Delta Force, or Marine Recon/Raiders remains more pragmatic due to their more agile nature. Calling in a drone strike against suspected terrorist cells is quicker, safer, and more effective than deploying conventional ground units. While the threat of global terror necessitates the creation of rapid response forces to oppose threats, the necessity of “breaking the phalanx” likely died out after Iraq.

With the Russian invasion of Ukraine and China’s military posturing around Taiwan, MacGregor’s recommendations seem to have died with a whimper across American defense intellectual circles. The US Navy and Air Force budgets remain as large as ever, and MacGregor’s model of a flexible brigade-based division structure was only partially realized with the occupation forces of Iraq.

Conclusion

While MacGregor’s analysis of flexible land-based power as being necessary for effective US power projection remains correct, it must be balanced with an appreciation for naval strike capabilities. MacGregor fails to appreciate the value present in carrier strike groups, and in my opinion, his recommendations – as of 2024 – only apply to one present theater of operations the US may soon fight a war in – the Pacific.

That will be covered in a future article, where I will give my own recommendation for US power projection in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, East Asia, and the Caribbean in response to both Russia and China’s resurgence in military and political power. In addition, I will discuss how our adversaries’ desires to expand their influence can complicate our interests abroad.

Stay tuned to the Jesuit Roundup for more geopolitical coverage!