It was February 23, 2009, when Admiral Patrick M. Walsh, Vice Chief of Naval Operations, appeared before reporters at the Pentagon to explain the results of a month-long review of the detention facilities at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base.

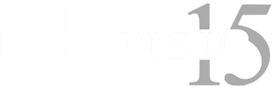

Situated on a bay that Christopher Columbus described as “broad…with dark water, of unsuspected dimensions,” the Guantanamo Bay Naval Station has served the US for over 100 years. However, the detention of prisoners that began after 9/11 as a result of the War on Terror has been the source of controversy ever since.

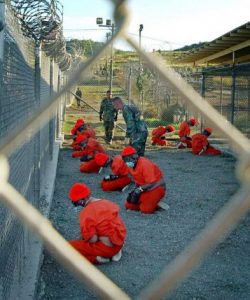

Since January 2002, the US has detained over 750 “unlawful combatants,” with 166 currently incarcerated, at Guantanamo Bay. Despite its mission to protect the world from some of the world’s most dangerous terrorists, Guantanamo became the source of relentless criticism by “human rights” organizations for what they considered to be various human rights violations. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as the World Health Organization and World Medical Association have voiced their opinions regarding many procedures that are applied at Guantanamo.

Most notably, President Obama, during his first presidential campaign in 2007-08, promised to close Guantanamo Bay in order to “regain America’s moral stature in the world.” Shortly after being elected to his first term, Obama issued an executive order on January 22, 2009, to close Guantanamo Bay’s detention facility within a year. However, this has yet to be accomplished, and Guantanamo Bay remains operational today because of the difficulty in finding any other location to house these prisoners. In addition to the president’s executive order, an official review of Guantanamo Bay’s facilities was authorized by the President. This process was undertaken, at the direction of the Secretary of Defense, with Admiral Walsh charged with informing the public about the current status of the prison.

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

Toward the Naval Academy

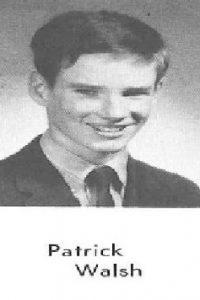

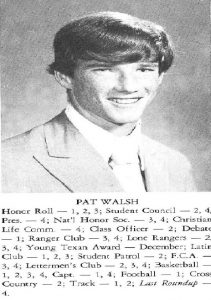

Walsh’s appearance before the national media came almost 50 years since he was a student at Jesuit College Preparatory School in Dallas, where he was known, among other things, for his prowess as a guard on the basketball court. In addition to being captain of the basketball team his senior year, he also played a huge role in Jesuit’s student government.

Walsh remembers a pivotal moment in his Jesuit career, during his junior year, when “in the course of events up in Montserrat and Lake Dallas, we had an agenda where we were determining candidates for student council president. That was not something that I was even remotely thinking about until one of my classmates came up and said this is something you ought to do. It was going through that process, being nominated by my peers and then voted on by my classmates to a leadership position that gave me exposure to leadership in a way that I had never ever dreamed of doing and once I did it, it became really a life changing experience for me.

So I found myself in significant leadership positions along the way, I guess that’s the best way to characterize it, particularly as a flag officer, but really for the bulk of the years of service that we had and I look back with gratitude for the junior retreat; I’ll always remember that.”

Entering the Naval Academy, Walsh aspired to continue playing basketball. However, an early season-ending injury cost him the chance. “I started to fall behind in class and had to make a ‘hard’ call about basketball,” Walsh says. “I needed to reset my priorities.” Focusing on his studies, Walsh made enough time to join Big Brothers and play in the intramural basketball league, where his team won the brigade tournament.

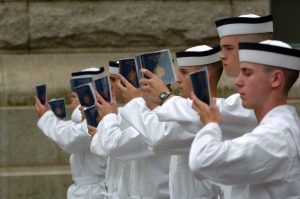

In many ways, his Naval Academy experience reminded him of Jesuit as “there were several faculty, staff, and coaches at USNA who gave the school its reputation, history, and tradition.” Among the subjects he enjoyed were the studies of American and International Political Systems, management, and English, as well as the core courses of Physics, Naval Architecture, Organic and Inorganic Chemistry, electrical engineering, and calculus. “The course work was rigorous, but at the beginning of each semester, each faculty member placed their home phone number on the board for us to call if we had any issues understanding the course work…I always remembered and appreciated what they did for us.”

As a student at the Naval Academy, Walsh greatly respected the Blue Angels, their air show always coinciding with the week of graduation. “It represented the best, as far as we were concerned. We could see the blue angels fly each year at the naval academy, they’d do an air show the week of graduation, so that was something I always looked up to.”

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

The Golden Dragon Becomes a Blue Angel

After graduation, Walsh jumped at the chance of becoming a Blue Angel and began his flight training.

Before becoming a Blue Angel, however, Walsh had to have a number of years of flying experience under his belt.

Joining the Golden Dragons of Attack Squadron 192, Walsh flew over the Indian Ocean in what is known as “blue-water operations.” Admiral Walsh recalls the command and expertise that was required out in the open ocean when there was “no other runway in sight, where all you can do is land on the carrier. You have to be thinking all the time in terms of the overall status and performance of the aircraft.”

In 1985 Walsh became a member of the Blue Angels. “It was really cool.” During his first year on the team, he flew in the #3 or Left Wingman position. “I spent the majority of my time in the air looking at a specific position on the Flight Leader’s (#1) plane, depending on the maneuver.”

In 1986 and 1987, Walsh flew the #4 or Slot Pilot position for the Blue Angels, which flies directly behind and underneath the Flight Leader. In this role, Walsh had an “active role in the safety and performance of the team by ‘backing-up’ the Flight Leader.”

During his time as a Blue Angel, his team transitioned from the A-4 aircraft to the F-18. Being a Blue Angel allowed Walsh to come back to Dallas and to his alma mater. “We came back to Dallas each year [and] took the Jesuit bus, filled it up with people, and drove out to the air show.”

Watch Lt. Walsh Flying #4 Slot Position with the Blue Angels in the 1986 Cleveland Air Show.

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

A Navy Pilot’s Trajectory

Following his years as a Blue Angel, Walsh’s career followed an increasingly consequential path. After being a White House Fellow from 1988-1989, he became a Combat Strike Leader during Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm during the war to remove Iraqi forces after their invasion of Kuwait. While receiving various military promotions in the 1990s, Walsh pursued academic advancement, receiving a Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy in 1993 and being awarded a Ph.D. in 1999.

After having various major leadership responsibilities, in 2005 Walsh became Commander of the US Fifth Fleet, which operates in the Persian Gulf, Red Sea, Arabian Sea, and the East African coast.

One event under his command involved the 2006 Lebanon War between Hezbollah and Israel. Many US citizens’ lives were at stake and would need to be evacuated. At the time, Walsh had been expecting to go home to a family reunion, but “we got a call that there was going to be an evacuation in Lebanon and that the war situation was starting to spiral out of control.” Despite his plans, Admiral Walsh’s real responsibility was apparent, so he “stopped everything, went back to the command-and-control center for us in Bahrain, and then exercised round-the-clock operations to evacuate 15,000 US citizens.”

In 2007, his experience led him to the position of Vice Chief of Naval Operations. It was during this period of his career that Admiral Walsh received his promotion to full Admiral after being nominated by President Bush and being approved by Congress for his fourth star.

In 2009, the Admiral became Commander of the US Pacific Fleet, following in such impressive footsteps as those of Chester Nimitz, who led American naval forces against the Japanese in World War II. In this position, Walsh had operational command of ships, airplanes and people. Unlike his position of Vice Chief of Naval Operations, which concerned such matters as budget and discipline, Walsh’s responsibilities involved “missions to accomplish. We had to be responsive and very dynamic on these missions and so a different set of responsibilities.” His command of the Pacific Fleet was an “around the clock” responsibility.

In 2011, while in command, Japan was hit by a devastating earthquake and tsunami. The US Navy, under his direction, responded to pleas for assistance: “I was in Hawaii. It was 10 o’clock at night, the instrumentation that was coming from the seismogram was just going off the page. Everyone thought there was a problem with the instrumentation, and when we realized we had a magnitude 9.2 earthquake, we realized we had a real problem.”

The resulting Operation Tomodachi, or Operation Friend, provided disaster relief from March to May 2011, involving 24,000 U.S service members from all military branches, 189 aircraft, and 24 naval ships.

Since we have an all-volunteer military force that is “professionalized” and “very, very capable,” it becomes difficult, according to Admiral Walsh, for such a modern military force to “sit on their hands when you have [serious natural disasters].” As he explained during a recent visit back to Jesuit, “It is in time of crisis,” says Admiral Walsh, “it is in that hour of tragedy, that moment of calamity, we learn about ourselves and the brotherhood of humanity.” Admiral Walsh looks at this operation fondly because “we had the chance to help the most people, and interacted with enough people from Japan to know that they very much appreciated what we did and how we did it.”

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

Flight 77 at the Pentagon on 9/11

While Walsh became Commander of the Pacific Fleet near the end of the first decade of the 21st century, near the beginning of that decade he was working at the Pentagon as Executive Assistant to Chief of Naval Personnel.

On the fateful day of September 11, 2001, Admiral Walsh remembers suddenly being “underneath the flight path of American Flight 77 going into the Pentagon. The wing came over our building…the engines were up, [and] it was very, very loud. I’ll always remember that. We had people who looked up and saw faces of passengers; they’ll be in therapy all their life.”

The events of 9/11 began the long-term War on Terror.

The United States was soon seeking to destroy Al Qaeda in Afghanistan and by January 2002, the US was bringing prisoners to Guantanamo for detention. Various groups, some of which were political opponents of the Bush administration and some of which were international human rights organizations, began to denounce the treatment of prisoners at Guantanamo. These controversies continued throughout the two terms of the Bush administration, leading to President Obama’s choice to close it.

One matter of controversy involved how the Bush Administration would try the prisoners at Guantanamo. Originally, they had set up a system of military tribunals to try them, but this system was declared unconstitutional in 2006 by the Supreme Court in a case known as Hamden vs. Rumsfeld. President Bush responded by asking Congress to pass the Military Commissions Act of 2006, which he signed, but which was also overturned by the Supreme Court during the election year of 2008. This court ruling, Boumediene vs. Bush, ruled the Military Commissions Act of 2006 unconstitutional because it did not grant detainees their habeas corpus rights. To fix this omission, the Congress then passed the Military Commissions Act of 2009.

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

Admiral Walsh Investigates GITMO

At the time of the court ruling in 2008, there were 270 prisoners at Guantanamo Bay. When President Obama came into office, the number had dropped to 242 detainees. Two days after his inauguration in 2009, he issued the executive order to close Guantanamo Bay within a year and ordered an official review of current conditions at the facilities, a review that became another opportunity for Admiral Walsh to serve his country.

Admiral Walsh’s appointment to inspect Guantanamo Bay came about abruptly while still serving as Vice Chief of Naval Operations. “In 2009, I was working at the Pentagon,” says Walsh. “They just walked in and said, ‘You’re going.’” In order to have a professional, respectable report, Walsh understood that it was important for the review to be completely “transparent” and that anyone be able to see the results.

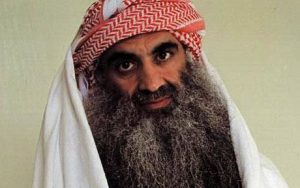

Making his report transparent meant that Walsh would see every nook and cranny of the facilities, even Camp Seven, where Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was being held. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, infamously known as the mastermind of the attacks on 9/11, was captured in 2003 and subsequently detained at GITMO, where he confessed to 31 different acts of terrorism. The location where Khalid Sheikh Mohammed is currently being held, Camp Seven, is the most secure facility in Guantanamo Bay, reserved for only the most wanted terrorists.

The review included talking to prisoners as well as officials in charge and representatives of human rights organizations interested in the fate of the detainees.

Walsh then organized his report based on a template explaining “the problem, followed by what the detainees say, what the human rights organizations say, then what the US policy was.”

One of the questions Walsh addressed was “What is it today [in 2009] that the human rights organizations find objectionable about Guantanamo today?” To answer this question and many others, Walsh established “25-26” different areas that pertained to every part of a detainee’s life at Guantanamo. According to Walsh, “We adopted the perspective of a detainee, from the time they arrive to the time they are repatriated. We looked at the arrival procedures, the showers, bathing, haircuts, mail, food, sleeping conditions, interrogations, and forced feeding.”

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

Public Perception vs. Reality

Simply put, “Guantanamo of 2009 was not the same Guantanamo of 2002.” According to Walsh, “conditions had changed remarkably” because of interventions by the Supreme Court and directives from the Department of Defense. Admiral Walsh emphasized that the public perception of Guantanamo Bay was outdated. For one thing, the detainees have a soccer field, a weight room, and 11,000 books and DVDs to choose from. Nutritionally, they receive 4,500 calories a day, and “get better medical care than some US citizens.”

But among the 25-26 areas of a prisoner’s life under review were some extremely serious concerns.

Forced feeding, for example, “was a hot button issue,” says Walsh. In 2005, some detainees went on hunger strikes to protest their detention at Guantanamo Bay, and some hunger strikes continued off and on over the years. In response to the hunger strikes, military officials followed certain procedures. “Any individual that had missed more than nine meals and exhibited change of chemistry in the body required forced feeding with a tube.”

According to Walsh, the World Health Organization (WHO) objected to forced feeding because they said it was “inhumane.”

Walsh’s committee asked the WHO when it felt these detainees, who were going on hunger strikes, ought to be fed. The human rights group answered, “only after they’ve gone into a coma.” The World Medical Association has also expressed its stance on forced feeding, calling it “a form of inhuman and degrading treatment.” Although it has not referenced Guantanamo specifically regarding forced feeding, its principles clearly articulate their position on the matter.

Admiral Walsh believes it’s important to know the policies not only of the World Health Organization, but also of Guantanamo Bay because “the public needs to understand…the actions that we take. Where the critique comes in is we’re not going to watch somebody go into a coma and run the risk of permanently damaging themselves; that’s an inhumane act as far as we’re concerned.” According to Walsh’s report, “Enteral [intestinal] feeding of hunger strikers for whom continued fasting might result in death or serious harm is being conducted as a medical procedure with the sole purpose of preserving life and health,” which complies with the Geneva Conventions.

Another area of concern involved religious practice. Detainees and non-government organizations insisted that Muslim chaplains be available to teach guards “how to be culturally and religiously sensitive to the detainees.” In practice, detainees are provided, among other religious items and activities, a Koran, prayer beads, cap, rug, prayer schedule, and a call to prayer sounded five times a day. According to the report, all conditions of religious practice are in compliance with the Geneva Conventions.

With regard to interrogation, another major area of concern, prisoners and NGOs insisted that any detainee “should not be punished or rewarded based on his cooperation,” and medical care should not be based upon prisoners’ cooperation, and that prisoners should not be subject to psychological coercion, sleep deprivation, and other degrading treatments. In practice, detainees may decline participation in interrogations “at any time, with no negative disciplinary consequences,” and medical personnel are not involved in any interrogation techniques. The Walsh report concluded that, in matters of interrogation, Guantanamo Bay is in compliance with the Geneva Conventions.

[box type=”download” align=”alignleft” ]Anyone interested in reading the entire Walsh Review Report at

REVIEW OF DEPARTMENT COMPLIANCE WITH PRESIDENTS EXECUTIVE ORDER ON DETAINEE CONDITIONS OF CONFINEMENTa.pdf

[/box]

After finishing the report, Admiral Walsh presented it to the Secretary of Defense personally and went to the White House to brief John Brennan, the chief counter-terrorism adviser and president Obama’s nominee for CIA Director, as well as other officials.

“The interesting thing,” Walsh states, now four years later, is that “after the report came out, nothing really changed at Guantanamo; it stayed open. All the lawmakers had the chance to see, but it didn’t close.”

The reason Guantanamo Bay was ordered to close was, says the Admiral, “the belief that people had over the course of many years that Guantanamo was a stain, that [it still] looked like the conditions in 2002.” Admiral Walsh’s review shows that the conditions at Guantanamo are now in compliance with military standards and the Geneva Conventions. According to the Admiral, when looking at the facilities today, “it would be very difficult to replicate this structure as well as the way it is run, anywhere in the US—it would be very costly and one would have to ask why close it if the facility is currently run in a legally correct manner.”

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

The Military and Politics

After more than four decades of intense involvement with the United States Navy, much of it near or at the pinnacle of command responsibility, Admiral Walsh remains concerned about the intense political divisions in this country and its effect on the military.

After more than four decades of intense involvement with the United States Navy, much of it near or at the pinnacle of command responsibility, Admiral Walsh remains concerned about the intense political divisions in this country and its effect on the military.

Having graduated from Jesuit when Nixon was President, Walsh has worked under several presidents in his career. “From Nixon to Obama there have been some significant excursions [around the world], but the important thing is that we have a consistent obligation to the Constitution, to the chain of command,” says Walsh. He explains how “political diversity” is important when it comes to the military. “I get very concerned about one military group being affiliated with one political party. We have enough polarization in the country and we have too much distance, I think, from citizens and the military.”

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

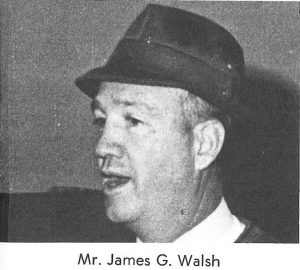

Dad

Throughout his years of service, Admiral Walsh has found inspiration in many leaders. Among the historical figures are Chester Nimitz; George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff of the Army during World War II, who later became Secretary of State under President Truman; Colin Powell, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1989 to 1993, and President George W. Bush’s first Secretary of State; and William Crowe, a Navy admiral who served during the Vietnam War and became chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. Admiral Walsh respects these men for the “way they thought, the clarity in which they presented their ideas, [and] their ability to communicate ideas.”

However, before the historical figures, “I’d start with my dad, a coach at Jesuit.” On the occasion of his retirement as Commander of the US Pacific Fleet in December 2012, Walsh spoke about his father, “the singular – most successful leadership model and example I ever witnessed… Admirals might have been interesting (to study), but coaches were gods! As a teenager, I could ride with my Dad to school…many years later, I learned to appreciate his upbeat outlook, optimistic view, and humming on the way to work…during the day, I could go see Dad in his office.

When I witnessed the parade of athletes in his office and years later, the generations of alumni who returned to the campus to see him, I realized what it meant to be truly wealthy in mind, soul, and spirit.” Even though Admiral Walsh has held many titles throughout his career, “the highest form of praise and the most respected title that I had ever heard, was the one earned by my father – he was known simply as Coach Walsh.”

When Admiral Walsh looks back on his military service, he finds that “the rewards are going to come differently than what you would find in other lines of work.” With service in the military, a person is able to contribute to the common good, “to a cause greater than yourself.”

Walsh’s observations about his military career are, clearly, a reflection of his education at Jesuit, where young men are taught to be men for others.

Admiral Walsh, whose official retirement from the US Navy took place March 1, 2012, has now returned to Dallas, where he lives with his wife, Andy Kaye, and their son Matthew. Their daughter is a freshman at Holy Cross University.

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

A Letter Home During War