So how did you spend your summer? Inspecting the intestines of fruit flies? Analyzing the effects of vaccines? Digging for a solution to cancer?

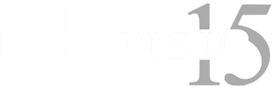

Actually, three Jesuit students, Patrick Arraj ’14, Trevor Johnson ’14, and Mason Amelotte ’14, respectively, accomplished just the above. Participants of the STARS program at UT Southwestern, a nationally renowned medical school with multiple nobel laureates, the terrific trio spent the summer performing advanced research and collaborating with professors highly respected in their fields.

Patrick, Trevor, and Mason worked in a professor’s lab for eight weeks, leaving little time for the stereotypical activities, such as lounging by the pool or vacationing in the country, that consume the summers of many. And though these students are merely weeks removed from the lab, the journey, in fact, began many months ago. Intrigued by the opportunity to achieve something “completely outside of their league,” says physics instructor Mr. Max von Schlehenried, Patrick, Trevor, and Mason actually began the tedious and multi-staged application process in the fall of their junior year.

Patrick, Trevor, and Mason worked in a professor’s lab for eight weeks, leaving little time for the stereotypical activities, such as lounging by the pool or vacationing in the country, that consume the summers of many. And though these students are merely weeks removed from the lab, the journey, in fact, began many months ago. Intrigued by the opportunity to achieve something “completely outside of their league,” says physics instructor Mr. Max von Schlehenried, Patrick, Trevor, and Mason actually began the tedious and multi-staged application process in the fall of their junior year.

Generally, science teachers introduce the program to junior students early in the year. “Ever since I heard about the program, I wanted to do it,” reflects Trevor Johnson ’14. So, much like a senior applying to college, he sent off a long list of materials which included a transcript and essays to UT Southwestern. Once complete, he, along with other applicants, participated in an interview with Mrs. Jan Jones, a freshman biology instructor, and Mr. von Schlehenried to determine if he was a strong match for the program. In this interview, the two seek to ensure that the applicant is academically qualified, mature enough to handle such a commitment, and possesses a truly strong interest in science.

“It’s a long process,” describes Mr. von Schlehenried, one that demands a student “who is passionate about science in some way. It’s not a discovery program.” Rather, it helps the student decide whether “[he] wants to do research” for a living, as opposed to helping him decide if he wants to pursue a career in science. This indecision between research and practice is something specifically targeted in the application process, and can help eliminate a few students immediately, allowing those more serious to continue competing for the two guaranteed spots that Jesuit claims each year. Obviously, as already indicated, three Jesuit students completed research this past summer, meaning that multiple students met the requirements to participate.

The final phase of the application entails an interview with the dean at UT Southwestern, an interview to which, somewhat surprisingly, since it is a program for the student, parents are invited. Trevor Johnson recalls his confusion: “We did the interview and what was interesting was that they actually had our parents come up here, which didn’t really make sense to anyone. The doctor asked my father [if he knew why he was here, a question to which he could not provide an answer.]”

Though Trevor initially thought that his dad’s uncertainty could possibly disqualify him from the program, he later understood that the interview primarily aimed to certify that the student’s parents “aren’t pushing him to do this. In their eyes, [the absence of a medical background] was good.” Following the interview, the committee then proceeded to match the student with a professor who he would concurrently work with and receive supervision from over the summer.

Of course, who couldn’t use a little comic levity in the midst of such an intense examination? During the interview, Trevor recalls that the dean asked him to tell a joke, likely requested to test the student’s personal skills. “I told a science joke,” he says, which was all he was willing to disclose on the subject, leaving the exact line an ambiguous mystery.

Of course, who couldn’t use a little comic levity in the midst of such an intense examination? During the interview, Trevor recalls that the dean asked him to tell a joke, likely requested to test the student’s personal skills. “I told a science joke,” he says, which was all he was willing to disclose on the subject, leaving the exact line an ambiguous mystery.

Once admitted, each student works on a specific project for the program’s duration; Trevor attempted to determine the correlation between the use of vaccines and the appearance of autism, a particularly relevant topic since many parents “withhold children from vaccines, which isn’t necessarily a good thing.” His cousin also battles autism as well, making his research a highly personal endeavor. To do so, he examined the density of calbindin cells (calcium binding proteins) in the brain of monkeys, some of which had been vaccinated and some of which had not.

“I spent most of my time sitting at a computer using this technology called Stereo Investigator. Basically, my computer [was] hooked up to a giant telescope that can zoom in 600 times, [allowing me to] outline the entire brain. That would take me about two hours because when you’re at that magnification, a millimeter takes a long time. When you start the counting [the cells], you have to finish it. I [then] exported the data, and it [gave] me all these estimates; it [gave] me the volume of the brain, which is for real since I just traced it; then it [gave] me an estimated mass of cells, [which] you use that to find the density that you can compare [from the brain of one monkey to the next]. I did this on sixteen brains, nine controlled and seven experimental. I would do this to different parts of the brain.”

His experiments suggested that only those cells “already not firing very much” were affected, indicating that vaccines only pose significant risk if other health complications exist. However, he was also careful of drawing any conclusions based on his work, since he only scraped the surface of what is a very complex and intricate topic. All high school students infamously understand the need for relentless testing before deriving anything conclusive, something beaten into them by teachers from an early age.

Trevor painfully recounts the tiresome nature of this often monotonous, laboring, sometimes excruciatingly annoying procedure: “It’s very meticulous, almost hypnotizing. You have to be in a dark room, no lights except the computer because you have to be seeing these small little cells.

These things take maybe three hours to do, but you have to do it two [or more] times to make sure you’re consistent. You do it the first time and you get one number; you do it again and get another number, which is far apart [from the first]. You do it a third time and get a different number [even farther apart than the second].” All the while, “no one is watching over your shoulder to make sure that you’re doing it right.” Unfortunately, one of the participants Trevor observed failed to complete his project since he used a pipet (calibrated chemical dropper) incorrectly over its span, an observation which he labeled as “very upsetting.”

These things take maybe three hours to do, but you have to do it two [or more] times to make sure you’re consistent. You do it the first time and you get one number; you do it again and get another number, which is far apart [from the first]. You do it a third time and get a different number [even farther apart than the second].” All the while, “no one is watching over your shoulder to make sure that you’re doing it right.” Unfortunately, one of the participants Trevor observed failed to complete his project since he used a pipet (calibrated chemical dropper) incorrectly over its span, an observation which he labeled as “very upsetting.”

Of course, Trevor classifies his overall experience as highly enjoyable; even though he basically forfeited his summer, “working nine to five, five days a week, for eight weeks,” the opportunity to meet and interact with such knowledgeable professors was highly stimulating. “I enjoyed meeting with Dr. German,” he reminisces, “because it’s amazing how much he knows. I’d ask him a simple question and thirty minutes later we’re talking about Parkinson’s. He can just go on infinitely. It was interesting meeting someone like that.” And, surely, he appreciates the prestige associated with adding this research, in fact, so prestigious that Cameron Kerl ’13, a STARS participant the previous year, received an invitation to again work in the lab this summer- to work toward his future goals, earning both an M.D. and a Ph.D., a dual accomplishment that will allow him to communicate “with both sides of the [scientific] spectrum,” both practitioners and researchers alike.

And it’s probably safe to assume that the $2600 paid to each participant was attractive as well.

While Trevor delved into the brains of monkeys, Mason Amelotte ’14 dove into the depths of cancer; he examined the possibility that “estrogen could influence [a gene called MT-3] and hopefully lower the expression of this gene,” which resists certain forms of cancer treatment, notably chemotherapy, therefore preventing the cure of the disease.

Mason confronted his Achilles heel, or one of his major challenges, several weeks into the project, when he was forced to modify his topic due to the lack of progress with his original project. “From my understanding of research, it’s very variable,” claims Mason. “Initially, I set out to work with fat cells and see certain gene expression levels, but once you finally do the tests things don’t always go as planned and you have to work around that. Within last two weeks we had to change the focus to chemotherapy resistance and estrogen.

Regardless, he, like Trevor, benefited personally from the confluence of experts with whom he worked. He relished the opportunity to participate in “an environment in which there was such a variety of people,” which, he states, “[was] beneficial by itself. At the same time, establishing those connections with people in the actual world of research [clarified to him that research] is something that [he’d] really like to pursue.”

Finally, last but certainly not the dimmest star, Patrick Arraj ’14 probed the intestines of fruit flies, which he asserts possess a similar intestinal system to those of humans. “What we basically did is knock down proteins in the fly’s intestines to see how the intestines respond to injury. We would see which proteins restricted or promoted proliferation.” Due to the similarity between flies and humans- talk about humbling- the implication is that those proteins which enabled regeneration of the intestine in a fly might do the same for the human intestine.

And, not shockingly in the least, he battled his share of challenges as well. “I definitely experienced failure,” recalls Patrick. “During the first few weeks, it was very hard to do some of the tasks. The program taught me to keep trying and to keep persevering.”

So now I ask: does impacting the medical field as a mere high school student sound interesting to you? If a common denominator exists between these three, it is that preparation begins a day from yesterday; to quote a Jesuit legend, one whom all are familiar with, “the time is now.”

“You actually have to want this because you’re working nine-to-five,” advises Trevor. “I only had one week of summer. You have to be a self-motivator,” a transformation that mandates time and attention long before one applies to the STARS program.

Mason agrees: STARS demands “someone who is very motivated and very fascinated with science. You don’t have to go in with a huge science background; I was in a regular biology class freshman year and working in a lab this summer. They want someone who can geek out, someone who’s kind of a nerd, and for whatever reason they saw that in me.”

Echoes Patrick: The ideal applicant must definitely work hard, “because it was eight hours a day, five days a week, for eight weeks; someone who is dedicated to science, willing to put up with all that work, because you are trying to catch up with everyone in the lab, people who have been there eight years.”

Mason, Trevor, and Patrick will each present their projects to the school at a future date, likely October 1, a presentation which all students are cordially invited to attend.