This is the last segment of the three-part interview and series with WWII veteran and historical track coach Herb Sheaner of Jesuit Dallas between his tenure in 1955-1975. In the last two articles, my fellow Roundup writers Anthony Nguyen and Peter Loh covered Mr. Sheaner’s early adulthood and his initial experience fighting in the Battle of the Bulge.

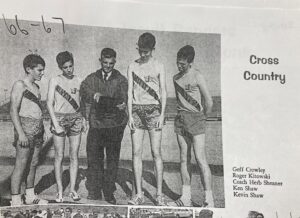

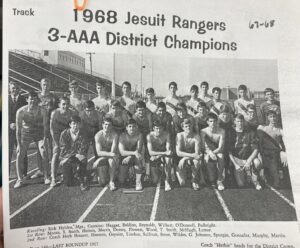

For this segment, we interviewed Mr. Herb Sheaner about his captivity in the Battle of the Bulge serving in the U.S. Army, along with his experience at Jesuit Dallas regarding his love for track and field. He also blossomed the sport into what it is today in Texas high school sports with a nomination to the Jesuit Sports Hall of Fame in 1999 and the founder of the Jesuit-Sheaner Relays.

Describe your march back into Germany and the physical toll and mental toll that took on you and your comrades.

You know we got captured on the first day. We were walked through. I would say maybe a mile or two out of the little town where we were captured by the time it was dark or getting dark, it was wintertime. It gets dark there, maybe 3:30 or 4 in the afternoon. It seemed like we just sort of made a circle in the snow out there in the field, hated it in Germany on the road, and just laid our overcoats while nobody ever got cold.

We were dressed so warmly and we’d just gone through such a bad experience. That cold was the last thought in our minds. And then we weren’t hungry either then because we’d had these nutritious D-bars for the last four or five days before we got captured. We hadn’t taken a little time before your body got down where you didn’t have, you just needed food.

We were just top notch physically when we got captured, just top-notch, you know, we were just, we’d been well fed three good old mills a day and I’d gone up to 161 pounds.

So nobody complained, you know. Now the Germans didn’t have much to offer us, but on the way back, some German truck came by going to the front and he had a big old, a gallon, five-gallon can of syrup is what it was. And so he stopped and the Germans gave it to my captain and he made a big circle of us prisoners. And we’d go by the captain and he’d give us one spoon full of syrup and then we’d go on and if we got around to ’em again, we’d get another spoon full until that can of syrup was six gallons was empty.

That’s what we had to eat. And you really didn’t get hungry until probably you got on the box cars and started to get back to Germany. On the western bank of the Rhine River (the main body of water that separates Germany from Western Europe), we were attacked by our own aircraft – the Germans didn’t put markings on the boxcars that they were full of American prisoners.

So the aircraft, our own American fighters, were shooting us. We got shot up. People were hit and someone two places from me were hit with the bullets from the aircraft and we were locked in this boxcar with no way to escape.

We weren’t hungry until later on. We didn’t get really hungry until we got to Germany two or three weeks later and they didn’t give us any breakfast. No lunch. Only down about that, about [Mr. Sheaner holds up half a cup] much of soup, and it wasn’t very good.

What was the mood of the men?

You know, nobody talked about anybody. Nobody talked. So it was, I guess you just say how in could this happen? But it just was unreal that we asked ourselves, how did it happen? They weren’t very happy. They weren’t talking to each other. It was just a done deal and just nothing cheerful about anything. It was just a bad, horrible situation.

We just walked for days and days. It was over a hundred miles back to the Rhine River, and we’d rather do that than get in a box car again and get shot up. There wasn’t much, there wasn’t any talking just with each other. This German boy came down a road on a bicycle and said, ‘we’re gonna win the war!’. I thought, well, I don’t know. I was asking myself, ‘Is this kid right?’

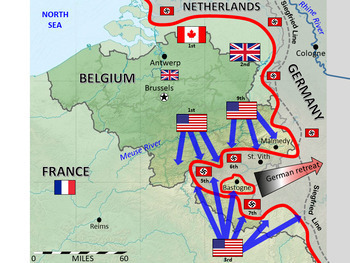

He’s right, you know? Because I think by we thought the war would be over by the time we even got to Europe that December, 1st of December, and here it is. But the Germans had amassed enough troops to overwhelm us, three field armies (~400,000 troops) against 4 divisions (~75,000 troops).

Well, that includes artillery and nurses and cooks and everything else. And the Germans also had thousands of tanks at least to start with. We didn’t have any tanks to oppose them.

What was the treatment that you received whilst being a prisoner of war?

Most of the stories you’d hear about prisoners of war would be the Air Force men that got women and men who would hit them with broomsticks. They definitely mistreated a lot of the Air Force boys, because they were the ones who really destroyed their homes.

But a lot of the civilians were nice to us on the way to our prison camp in Germany. On Christmas Eve, a German lady came out of our house who hadn’t quite reached the Rhine River for a march back to the river, and came out and gave us all cookies. And then that little boy you read about on a bicycle confronted us. He came down on a little road coming down to the road we were walking on, saying ‘we’re gonna win the war. We’re gonna win the war.’

I didn’t know whether he was right or not. The war wasn’t looking so good to me. I mean, we got overrun there. None of this was supposed to happen. Because we were captured, we didn’t know what was going on in the outside world.

I was a young guy and I know one German woman asked me what branch I served in. I was thinking at the time that the Air Force people, you know, had all the goodies and everybody was a sergeant and everything. There was a lot more to being an airman. And she told, asked me what I was in. I was a prisoner going back to prison, walking back to the Rhine River. I said I was in the Air Force.

Hell, I lied. I thought she’d like me if I was in the Air Force. No, she did not, because, but I didn’t realize that they didn’t like Air Force people. Cause they were bombing the heck out of Germany. They bombed all of these houses and killed so many people. She just looked at me with spite in her eyes.

Could you give a physical description of the camp?

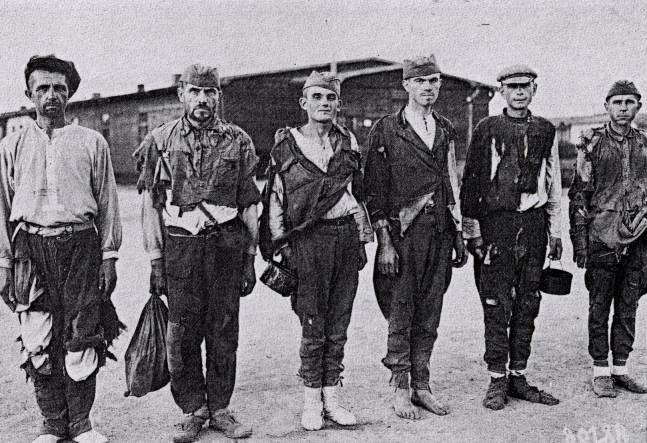

It was Stalag IV-B. Stalag was the name for the German prisoner-of-war camps. Well, sure enough there that’s where the winter was. Because we were in Eastern Germany in the snow. They removed the bar across the sliding door on the box car. So we got out and jumped down on the snow, and we stepped in to form a big line that came by and then went and leaned on a fence.

And just like a wood barracks there, we opened up and nobody talked. Nobody had anything to say. It was about midnight, we didn’t know what to think.

Mostly the camp had British prisoners, but they had some Russians in there too. They had some Indians, and they had different nationalities, not just British. We went in and the first thing they did was to get everyone to go one at a time and the doctor would ask your name or what you do for a living before you got in the Army.

You immediately march on, going with the next guy and then the next guy gave you a shot in the chest. We got shots up in the arm for the flu.

And we got inside and just one of the first barracks I came to they put me in there and it was full, but they found a bed for me. The Germans did and told me, to get in that bed, and it was in the British barracks and they played dance music from that, that past summer. And it was January or February, you know man, I thought I’d died and gone hearing all that pretty music, but they were playing it on a phonograph.

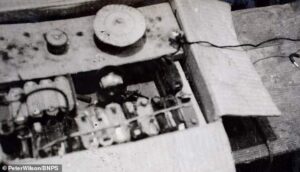

The British had been there so long that they, they had were getting BBC reports on their hidden radio, but never the Germans never found it. If they found it, the British would just create or smuggle one in again! I wasn’t there, but maybe two or three days before they got a hundred of, of, of the privates and put us on a train that’s gonna ship us out to work on some farms digging creeks or something else.

By the time of this physical labor, was it springtime and was the weather looking better?

No, it was still winter when they made us do the physical labor on the farms. Oh yeah, it was real cold. Sometimes the German guard would build a little fire and let one man at a time come over to warm his feet. But when you got a hundred guys to warm up, not everyone gets a chance.

Somebody would get up there by the fire and the guard said you can stay 10 minutes or five minutes. He didn’t care at all. He just stayed there for 30 minutes and, just stayed there by the fire. And the guard wouldn’t be there.

So we had about four or five of that kind of guys, out of a hundred of us that were, you know, this kind of people were a bunch of lowlifes. They might have been 30 years old, but they were taking advantage of everyone else whilst it was so cold.

But you got used to it being cold eventually. Cause that fire was really, really helpful. If one of the prisoners wouldn’t stay there too long, the German would keep putting a little wood on it and letting us get there, one at a time around that fire.

We had our wool clothes on and army wool hats pulled down. We never took our clothes off during the night either cause it was cold, too cold at night where we slept. We just slept in our clothes and the only thing to take off was my shoes.

And we had a blanket in the bunks we could throw on ourselves. The Germans put two men in each little bed that helped you keep warm.

That’s when the talking began, in the barracks. Everybody talked about grandmother and aunt and mothers and what all they cooked and all we could talk about was eating food. There was no talk of anything else, no talk about girls, or the war, just food.

The last thing, everything was just food. That was the most important. There nothing, man, I tell you that was, it felt like you’d been thinning by morning all that other stuff wasn’t on your mind. That’s just all you could think about was what your mother used to make and what your aunts would bring over.

Just nothing but food, and the guy from Iowa would say, well, I eat about hot cakes. Describing so many hotcakes on top of each other while we all feel we’re starving to death. But we just had to talk about it and listen to it and what really, I guess, really saved our lives. Near the end of the war, the Red Cross.

The Germans brought them into our compound where they kept us in this big eating hall of a cafeteria.

The Red Cross brought these boxes of food to us. We got each of us, we get to get a box, and that, uh, would last about two weeks and then another box so we could have even more. That was, I think that saved our lives, undoubtedly.

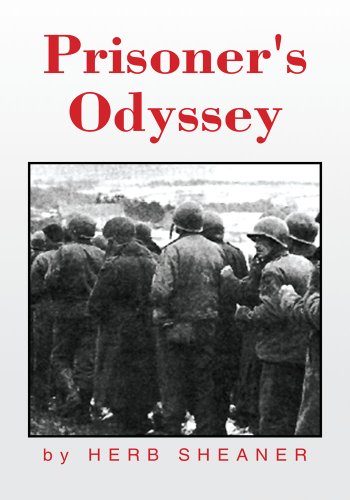

***Note: Towards the war’s end, Mr. Sheaner would find a way to escape from Stalag 4B. Although this aspect of the story was not covered in the article, Mr. Sheaner’s book, A Prisoner’s Odyssey, covers this aspect of the story. I will quote the book below.

“I had no idea what was going on by April of 1945. We had no idea the Russians and Americans were closing in on Germany… but we knew the war was winding to a close. There was artillery occurring closer and closer to the camp. Eventually, we were marched to a separate prison camp, where a German army officer commented that ‘It will all be over soon boys’.

When we sat down on the road, our guards, two young German boys, looked defeated already. I heard engines down the road… it felt like the last day of school. We looked down the road, and multiple jeeps of American soldiers came down the road. They looked fresh, healthy, and giant. It was like coming back into this world from the dead. This feeling surpassed all feelings that I had ever known.

We raised our hands to get their attention, but the jeeps passed by without stopping! But the last jeep turned around and came back. The driver stopped and commented, ‘See Captain, I told you they were Americans!’ The ride back was hard, my bony body was being bounced around like a ping-pong ball in a washing machine.

I looked to Frank [a friend he had made whilst in the prison camp]. ‘We survived Frank! We’re going back to American forces!’ I sent a message back home to Dallas Texas, saying I was free and in American hands and I was all right.”

What was coming back home like?

It was summertime when I got back to Dallas. My mother, who received word that I was alive, put up the Christmas tree, so at home, we came out, took a picture of it, me and my mom, and the fully decorated Christmas tree, she was going to give me those presents that I missed being a prisoner of war.

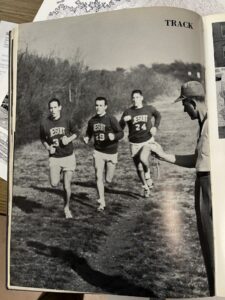

The war was over by that time. I was back home, and I was now back in Dallas. Remember, I had some experience in football and I even did a little track and field whilst in the University of Alabama. I was really good at the 50-yard dash – nobody could beat me at that.

And then when I came up back to Dallas, Mike Smith, was the football coach at Jesuit Dallas and he was a standout defensive back for the Notre Dame football team. Well, he must have heard about me. He talked me into joining the Jesuit Dallas track team coaching staff. He said, would you mind coming out and taking over my track team?

Oh my God, I’ve got a passion for that. He didn’t know it, but I did. I stayed here for 21 years. I did! And I loved it. That new part of my life was a passion for me.

My team turned out well, throughout the years we got kids into the discus throwing state championships, hurdles, and sprinters too.

The team turned out pretty well. We set the discus record in 10 meets in a row, all in the name of Jesuit!

But it seemed like every three or four years I’d have a boy who was another state-qualifying champion! It was the best mile or the best sprinter in Texas, or the best hurdler in the regionals who went down to Houston to compete in the local tournaments.

The experience of coaching, and helping these kids with their track and field careers, that’s a whole different life from being in the army.

How do you feel your previous experiences in the army impacted your coaching?

Well, I always felt like in the army I got an aspect of leadership, leadership that was initially started in High School. You know, I graduated a major and I had a whole company commander and I was a no-nonsense type of guy. Even though I was five foot four! My saber dragged on the ground, I’m guessing, but I still knew how to put someone to sleep with it. And in High School, I got my first experience in track and field.

Later when I became a coach, I carried some of that no-nonsense traits with me. I’d take some of the boys over if they were late getting to a recreational meet, and I’d set them outside on the grassy field before we got in the stadium. And because they were late I told them I just might pack you up and go home. I wasn’t about to do that. But they didn’t know that.

But if they had challenged me, I’d break my heart. I was tough. And they loved me. Jerry Patone was the team captain one year. During the Texas Relays, he was making too much noise in the hotel room, so I got him out of there. He later became a track and field head coach at Oregon State and I made him sleep on the floor right by my bed!

Other coaching staff and I would bring coffee for the boys, I paid for those and brought ’em to help my boys. If you have a true passion for the thing you do, you’ll do anything for the sport.

I really enjoyed the job, but once I got to be 51, I didn’t look as young as they did and I just, I just feel like I wasn’t quite the same. I just didn’t feel as good comfortably and so I retired from coaching, but when I first started coaching here, they thought I was young as they were because I mature so late! And I was a young-looking guy, very young. And although I was 30 when I first came to Jesuit they thought I was much younger.

When I got older, I got to participate more in veteran events, such as going to the countries I served in during my time in the Army! I went to Europe when I was in my 90s for a trip.

How long was this trip to Europe?

Oh, we spent about a week, so it wasn’t very long, but we were going back to the anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge, and we got to end up in the Ardennes. And we went to the residence house and in Luxembourg; we got to meet the King and the Queen of Belgium! We also encountered Nancy Pelosi and I got to venture to St. Vith in the Ardennes Forest.

What’s the secret to reaching 98? What is the secret?

I think it’s just in your genes. Like I say, when I started coaching it, I was 30. I was here first set foot on Jesuit. I was 30 years old, and some of the parents thought I was about as old as the kids in high school. I guess matured later, you know? And it has just been that way all my life. It wasn’t good for me to get in the Army when you look like a grade school boy.

Because in the Army they want real men. And that’s where I wanted to be an officer. I wanted to go to West Point, but I was too young and too small. I wasn’t that young, but I just didn’t grow up there. So no secret recipes, sir. No secret recipes every day. I do eat two apples a day and I get to be 98.

I’ve had some health problems in the last year or two. I know I left the bathroom and suddenly I just passed out and I fell down. I was suffering from a urinary tract infection, but they got that sorted out.

That’s what my daughter says. I didn’t trip or stumble. I just passed out. And I’ve had a hip replacement and small things still happen but I’ve gotten over them. When I was 80 or something midway in my eighties, I could run up a flight of stairs or in the bleachers at this school, and get to the press box.

I can’t do that anymore. I can’t even get them up unless I go up, there’s a handrail. But these young men, Jesuit men in their 20s or younger always are there to help me. I’m so proud of Jesuit and all of you guys.

Conclusion and Acknowledgements

Throughout this wonderful experience of research, interviews, editing, and planning for the trilogy of articles covering the experiences of Mr. Herb Sheaner, Anthony Nguyen, Griffin Taber, and I have received instrumental support from numerous faculty and teachers.

Dr. Degen organized the event alongside Mike Sheaner; the interview was possible with them. Ms. Row, in charge of the Jesuit archives, generously allowed us to research into Jesuit records of Mr. Sheaner in preparation for our interview. Ms. Katy Wilson also photographed the event to help us get some photos. From the bottom of our hearts, we thank these kind patrons for the truth-seeking, intellectual thought, and curiosity that the Roundup strives to offer Jesuit.

As we got up to end the interview, Mr. Sheaner kindly signed all three of the books we brought for the event. Although I had been amazed at his story before, at that moment, I truly began to realize how lucky we were with interviewing one of the last few surviving WWII veterans alive today.

As we filed back to the front desk entrance, Mr. Sheaner turned slowly to face us. “You know, boys, right now, the world is in a crazy spot. We could have war before Christmas, just like back in my time. I don’t like how we can destroy the world with a few button pushes and nuclear weapons. All you young men can do is stay strong, maintain discipline and respect for others, and pray for your families and communities. That’s all you can do now.”

Again, we would like to thank Mr. Herb Sheaner and all of those who made this interview possible. Coach Sheaner has been and will always be a significant part of the Jesuit Dallas community. Thank you, and stay tuned to The Roundup for more community profiles!

Sources: Sheaner, Herb. “A Prisoner’s Odyssey,” Xlibris Corporation, 2009