“The whole point of feminism is being equal and the playing field being equal.” — Michele Elchlepp, Theology Department Co-Chair

“I guess my question is, if feminist is the negative, what would be the positive?” — Anne Blackford, Mathematics Department Co-Chair

“At its core, the question to ask is ‘do you believe in equal rights?’ If you do, you believe in feminism.” — Erik Burrell, Director of Diversity

“There has to be recognition that the baseline definition of feminism is that men and women should be equal.” — Katie Segal, World History and US History Teacher

“Feminism is simply the belief that women are equal to men.” — Christina Ellsworth, Sophomore Theology Teacher

After hearing that Zach Bennett ’15 was writing “The Myth of Male Supremacy,” an article in which he talks about some of the problems males face and places the blame at the feet of feminists, I started thinking about my own experiences with feminism and gender roles and stereotypes. The word “feminism” specifically seemed so divisive among people, with some famous and influential people embracing it and others rejecting the term.

Partway through my sophomore year, a friend asked me if I was a feminist. I gave the only logical answer: yes, I believe in the equality of the sexes. “I do too,” he responded, “but are you a feminist?” Realizing he was referring to man-hating, radical Tumblr users, I responded with a firm “no.” I was not a feminist. That night, I decided to look it up.

The dictionary definition of feminism was “the theory of the social, political, and economic equality of the sexes.” As far as I was aware, it hadn’t changed to “the theory of the complete and utter destruction of men” between the time my dictionary was published and the time I read the definition. So, yes, I was in fact a feminist.

Personal Experiences

For me, a dictionary definition simply wasn’t enough. I wanted to know whether real people I care about and respect also decided to embrace “feminism” and its message of equality. To get more perspective on the issue, I decided to speak to Mrs. Anne Blackford, a much-loved algebra teacher and co-chair of the math department, about her own experiences. “I find it interesting that in 2014 we’re having this discussion.” Mrs. Anne Blackford shared with me as I walked into her office on a cool December afternoon. “I just don’t get it.”

Recalling her own past experiences with discrimination, Blackford remarked, “In our society, supposedly everyone has equal rights. I was told once that I could not be hired for a job as a math teacher because everybody knows men make better math teachers than women. He told me that if I were a man, he would hire me because my credentials were perfect.” The only problem, she said, was that she was female.

“That’s kind of what I think when somebody says to me that being a feminist is being an, I don’t know, an anarchist or a terrorist,” she said. “I can’t see it as a negative. And if I’m a man-hater, I’m certainly in the wrong job. I teach at a school with all boys, and I have two sons and two grandsons.”

As we spoke, Blackford took issue with the often-recited belief that feminism is detrimental to societal progress. “To make a sweeping statement that one change in our culture—which I see as progress—as being the reason for many things that you may not agree with or you see as declines in our culture,” she said, “seems pretty naive and not very well-researched.”

A Feminist Theology

Interested in a Catholic theological perspective on feminism, I ventured into the office of Mrs. Michele Elchlepp, co-chair of the theology department. “The definition that is being used to describe bringing men down is completely incorrect,” she explained. “It’s actually a talking point for über-conservatives and talking-head people that feminists hate men. Men are feminists as well as women are feminists.”

“To say that you don’t want equality for anyone or that feminism brings things down is the same as a Christian saying, ‘All Muslims should die because Islam is an evil religion,’” she said. “Morally, the Church teaches that people should be treated equally and well.”

As Elchlepp explained, Catholic social teaching since Rerum Novarum’s issuance in 1981 has dealt with a fair wage for men, women, and children. As the Church moved forward, it took on issues of a living wage (not simply a minimum wage), health care issues, and the ability for one parent to be able to stay home.

“Feminism in the Bible is all over the New Testament. Any time Jesus interacted with a female, he treated her as an equal,” she said. “It’s really the Roman culture of the time that shifts that. There were probably leaders of the Church that were females in the first century, and eventually that got weeded out as Romanization happened.”

She went on to explain that currently the Catholic Church bases its current decision for church hierarchy to be composed entirely of men because the Twelve Apostles were men, but Pope Francis has called for greater leadership roles for women.

“Where in any of Jesus’ teachings is there anything but total access to him?” she asked. “To me it seems Jesus was the first feminist in his culture.”

Ms. Christina Ellsworth, a sophomore theology teacher, agreed. “The theological foundation is there for feminism. There’s no theological foundation that says women are inferior to men,” she said. “If there was no Mary, we’d have no redeemer. She was the birther of God.”

Breaking Down Gender Roles

After both my own personal research and conversations with Mrs. Blackford, Mrs. Elchlepp, and other teachers, I started to realize gender roles can be incredibly harmful when they limit people’s potential. People’s biological sex shouldn’t solely determine their interests or how they present themselves to others.

In my conversation with Ellsworth, she added another important point: gender stereotypes affect both men and women, and feminism’s attempt to break down gender roles also frees men from socially-constructed expectations of masculinity.

“The gender stereotypes of men can be equally as oppressive as it is for women,” she said. “We have these expectations that men must be ‘manly men,’ and in order to be a man, you must objectify women, not have emotions, not feel for anyone, not cry, not be vulnerable. All of those things are beautiful human emotions that I would say, as someone who teaches theology, is the center of who we are supposed to be.”

Blackford felt similarly on the issue of gender expectations, citing herself and her daughter as prime examples. “I have a daughter who’s a tax attorney, and of my three kids she was the best student in math and science and the best athlete. To assign specific qualities to male and female is absurd. I’m a sports junkie. I also love to fly-fish,” she stated. “That’s not what women are supposed to do. And they’re not supposed to be good at math.”

When it comes to gender roles and expectations, it’s not feminists that are problem; it’s precisely the opposite. Conversations about gender stereotypes and roles for both men and women are an integral part of what feminism is today, and the most common sentiment among mainstream feminists is that gender stereotypes are harmful for everyone—men and women. Within feminism is the idea that men should not be expected to always be the hero or to be one-dimensional “tough guy” characters. Feminism is just as concerned with the expectation of young boys being knights as it is with young girls being damsels in distress.

A clear example of how patriarchal ideas of gender roles affect society today is in cases of child custody cases. Often it is still assumed that the father is the “breadwinner” who must financially support the children while the mother is the “caretaker” who must take care of the children. This concept leads to the majority of child custody cases ending with the mother gaining custody of the child and the father paying child support, even when the father can be just as capable of raising his children or the mother can be just as capable of financially supporting her children.

“In bringing this conversation to awareness and talking about gender stereotypes and how they’re false categories and not absolutes,” Ellsworth continued, “it’s liberating for both men and women.”

Unequal Pay and the Career Gap

As I continued reaching out to other teachers, the experience of dealing with forms of sexism—from being passed over for a job to being viewed as less capable of intellectual discussion—led them to identify with feminism and its principles. Of course, feminism is more than just an attempt to break down gender roles. Men and women are still undeniably unequal in the United States and abroad. One example of this is the pay gap between men and women. Using data from the U.S. Department of Labor, the 2013 median annual income for women was $39,157 the median annual income for men was $50,033. This means that, on average, women earn 22% less than their male counterparts.

While some critics, such as the American Enterprise Institute, have claimed that the pay gap is a result of women choosing lower-paying professions, the American Association of University Women showed that even after accounting for college major, occupation, economic sector, hours worked, months unemployed since graduation, GPA, type of undergraduate institution, institution selectivity, age, geographical region, and marital status, there was still a 7% unexplained gap between males and females one year after college graduation. Ten years after college graduation, the gap widens to 12% among full-time workers.

And when pay discrimination does occur, present-day legal protections such as the Lily Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009 are on the books because of feminists of all kinds—males and females. Despite gains, more protections are needed, such as the Paycheck Fairness Act, which would close loopholes in the Equal Pay Act of 1964 and make it easier to take action against an employer paying less on the basis of sex. Feminists are, once again, the group leading the charge.

Inequality absolutely exists within the professional world. A Columbia Business School study found immense gender biases in hiring managers for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, a clear example of how women don’t simply “choose” to not become scientists or engineers. When it comes to student evaluations, a North Carolina State University study found an inherent bias against female professors. And of course, the fierce majority of American politicians and business leaders are male.

Especially in the cases of women leaders, we can see examples of these biases in the language we use to describe them. “When women do the things that men do in order to get ahead, they’re referred to as overly aggressive or bossy,” history teacher Mrs. Katie Segal said. “When those same characteristics are prevalent in a man, it’s leadership. He’s a good leader, he’s steadfast.”

The Right to Be Equal

While there are many types of feminisms all across the globe, feminism in the United States is often conceptualized as three separate waves of activism. First-wave feminism began pre-suffrage and focused on gaining legal rights such as the right to vote and property rights. Second-wave feminism began in the 1960s as women entered the workforce, fostering the debate over sexuality, reproductive rights, family, domestic violence, gender roles, and other things. Third-wave feminism—coined by Rebecca Walker, a bisexual, African-American female—began in the 1990s and continues today. To rectify feminism’s previous focus on white, middle class women in the developed world, third-wave feminism seeks to include women of color, non-heterosexual women, low-income women, and women in the developing world. While it is much harder to define, third-wave feminism often deals with gender roles and stereotypes, workplace inequality, and fighting rape culture and domestic abuse, while acknowledging the intersection of race, gender, sexuality, and class in these issues.

In the 1980s, second-wave feminists dealt with a unique challenge involving legal rights: the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). As other teachers had shared with me, assistant principal Mr. Fred Donahue had been at the forefront of the attempt to ratify the ERA in Oklahoma. Further, Donahue exemplified the meaning of being a male ally to the feminist movement, an often-overlooked part of the struggle for equality.

When I walked into Donahue’s office, I was greeted by political buttons and a copy of the ERA text. Donahue, the political action chairman for his pro-ERA local teacher’s organization in Oklahoma during the early 1980s, lobbied the state legislature to ratify the ERA—a simple addition to the United States Constitution that stated, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex,” and would have given Congress the power to enforce this provision.

As one of the last states to vote on ratification, Oklahoma became a focal point in the national ERA debate, and the proposed amendment was defeated mostly by conservative activists and fundamentalist religious groups. The ERA ultimately failed, coming three states short of ratification in the necessary timeframe.

“The opposition was ridiculous,” Donahue remarked. “The surface opposition claimed that if we passed the Equal Rights Amendment, we’d have to have unisex bathrooms. If we passed the Equal Rights Amendment, a woman would have no right to be supported by her husband, women would have to go into combat.”

Donahue explained that while the Civil Rights Act of 1964 allows some protections on the basis of gender, without an amendment the judiciary could gut the provisions of the bill in the same way the Supreme Court has gutted much of Voting Rights Act of 1965 in recent years. “What’s to keep the them from going back and interpreting the ’64 Civil Rights Act in a more restrictive way?” he asked.

But it wasn’t just about legal protection and protecting equality from future courts. Quoting the arguments his sister used to cause him to support pushing the ERA, Donahue shared, “If you really believe it, it should be in the Constitution.”

Asked about the shift in gender equality from then until now, Donahue mentioned “In many ways, gender equality has advanced, particularly in medical schools, law schools, and graduate schools,” he remarked. “On the other hand, it’s very obvious that we still don’t have anything close to equality in pay. Poverty is more common in females than males. Obviously, government is still overwhelmingly male. In one sense there have been some very significant advances, and on the other hand there is some very significant evidence of inequality.”

As I finished my interview and began to leave, Mr. Donahue left me with a powerful parting story about his own family: his mother was a combat veteran and member of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps in World War II’s North Africa, Sicily, and Italy campaigns. His father was also a combat veteran and career soldier who stayed in the army after the war. “When I looked at my parents, I was looking at two veterans of World War II, who were in my mind, equals,” he said. “When anybody likes to say [negative] things about women, I refer them back to First Lieutenant Mary McGuire. When you’ve come back from three campaigns equivalent to the ones she hit, then you can talk to me about women not being capable.”

Finally, Donahue cited his own experiences with a new female, African-American soldier in Iraq. “She could drive me all across Iraq with an M-16 on her lap, sticking out the door flap of an unarmored Hummer. So again, when guys here tell me what women can do and can’t do, I tell them about the woman who drove me all around Iraq,” he told me. “She seemed pretty damn capable.”

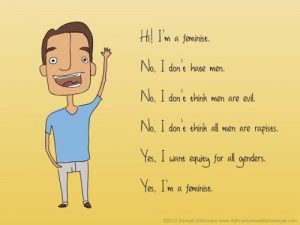

Feminism: Not Man-Hating

One theme on Internet conversations critical of feminism, especially on Internet forums and social media, is that feminism is actually the problem for women. The often-repeated claim, especially from some teens and young adults, that feminism is simply a bunch of “social justice warriors” who complain and fear-monger on their blogs is insulting to the many male and female feminists across history. It ignores the incredible amount of philosophical and theoretical discussion spurred by feminism, and it disregards the men and women who have fought tirelessly for equality for over a century.

Just like other movements, feminism isn’t best represented by its extremists elements, and it’s unfair to define feminism simply by cherrypicking its most radical elements and ignoring the rest. If we decided to define groups by their most radical adherents, we would define the pro-life movement by elements who bomb abortion clinics and kill doctors who perform abortions (the Army of God). We would describe environmentalists as eco-terrorists who bomb factories (the Environmental Liberation Front), Muslims as jihadist terrorists (al-Qaeda), and Christians as people who picket soldiers’ funerals (the Westboro Baptist Church).

Let’s address some common misconceptions about feminism found in “The Myth of Male Supremacy” and perpetuated by those quick to stereotype third-wave feminism as man-hating. Yes, patriarchy, the system of disadvantages faced by women, is real and affects men and women around the world. And no, feminists haven’t trademarked the word “patriarchy.” Yes, anyone can be a feminist, including men. No, heterosexual white males are not the enemy. No, feminism is not the reason for so many men being homeless. No, feminism is not the reason male victims of abuse have trouble speaking up. No, feminism is not the reason men are subjected to the expectation of being “masculine.” No, feminism is not the reason for body image issues for men. And no, feminism is not the reason for discrimination against men in custody battles because the courts think women are better mothers. (Actually, you can blame patriarchy and its rigid gender expectations for the last four.) No, “kill all men” is not, was not, and never will be a feminist ideology. No, “male tears” is not a feminist “thing.” And yes, feminism is, by definition, equality in the context of gender and sex.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sz7ZzQbSiGA

The aim of feminism is not to bring down men. “It really is impossible for those in the margins to pull down those in positions of privilege,” director of diversity Mr. Erik Burrell stated. “I don’t understand how it’s pulling down men unless you’re already saying women are less than men and you want to pull down men to their level.” And as Burrell further explained, feminism is not attacking men either. “It’s attacking the idea of treating people unfairly and in an unequal matter.”

“That argument that by women trying to gain equality means that women are trying to degrade men is the same as what white southerners were saying after the Civil War: if we make slaves free, they will enslave us,” Segal shared. “One group gaining equality doesn’t have to mean other groups lose status. By one group trying to rise up doesn’t mean that others have to go down.”

What Can You Do?

At the end of the day, we can’t just ignore the issues of sexism in today’s world because the issues impact men and women. As Ellsworth explained, “If we want to fix this at all, we have to recognize there’s a problem.” The first step is to be aware of our own personal biases, including gender biases. “We’re all biased. It doesn’t mean you’re sexist or racist,” Burrell explained. “Our job is to, as much as possible, evaluate people on an individual basis. If we know we have biases, the reaction should be, ‘Alright, I recognize I have biases, and how can I make sure they don’t creep into how I view a person or situation?’”

“I teach at Jesuit for the opportunity we have to teach students about all of life, not just the academic part,” Blackford said at the close of my talks with her. “It matters more to me that every student I come into contact with be a human who works for justice for all humans than whether or not they can solve a quadratic equation.”

As Jesuit students, we must challenge our own views about the roles of men and women when they limit each gender. As Jesuit students, we have an obligation to be aware of inequality to speak up when we see it. Most of all, we have to view the women in our lives as equal to and as capable as ourselves. As Donahue said, “The biggest thing for Jesuit guys is to be very open to the women in their lives as individuals and as intellectual entities.”

Be open to the idea that feminists and feminism are not what you hear about from talk-show hosts and Internet forums. Be willing to talk to your mothers, grandmothers, sisters, brothers, fathers, and grandfathers about the importance of equality. Talk to your friends—both male and female—and your fellow classmates, and don’t be afraid to lead and start the conversation on these often undiscussed topics. And finally, talk to your teachers. After hearing about their opinions and experiences, I can assure you that you’ll be glad you did.