In a few short months, the Class of 2024 will find themselves on a new journey as we embark upon our college careers. I feel that now is a particularly apt time to look to the past to one of the most incredible journeys ever undertaken. Mankind has always been driven by a base impulse to explore, to build a world beyond the one it already knows. Most know about the voyages of Columbus, Marco Polo’s journey, and the expedition led by Lewis and Clark, all tremendously impactful men. However, few know of those who charted the way, the explorers who came before. In this article, I will examine the incredible story of one such explorer from Classical Antiquity, the Voyage of Hanno the Navigator, while intermittently taking asides to provide historical context.

Hanno the Navigator

Little is known about Hanno the Navigator’s life, as all Carthaginian records were destroyed in the city’s sacking. However, a copy of a partial Greek translation of Hanno’s periplus, a document akin to a captain’s log, is the primary source for information about Hanno’s voyage, supplemented by other documents. He was from Carthage (modern Tunis, Tunisia), a colony settled by Phoenicians from Tyre (Lebanon), which had, by this time, asserted itself as the dominant maritime power in the Western Mediterranean. Hanno appears to have been the son of Hamilcar I of Carthage, who had either been the city’s king or its chief magistrate (Shopet).

First Steps

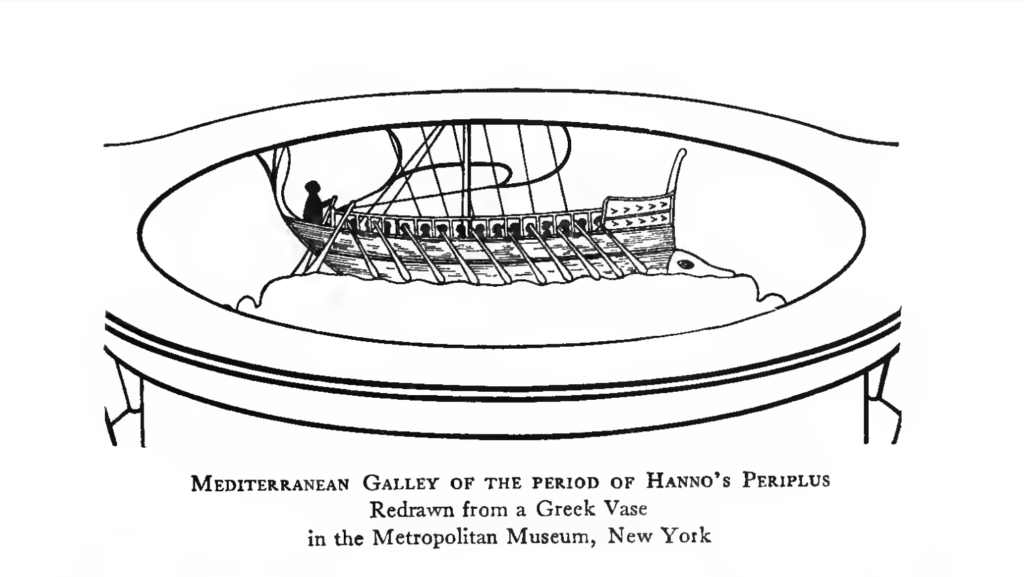

When Hanno took power, Carthage was still in the process of securing maritime dominion over other wayward Phoenician states and was eager to monopolize newly opened trade routes. To this end, the Carthaginian Senate entrusted Hanno with sixty galleys and thirty thousand settlers with which he was to explore the area beyond the Pillars of Melqart (Straights of Gibraltar), set up colonies, and bolster trading connections with the peoples of the region. Modern scholarship suggests that the number of thirty thousand colonists specified by the periplus, while not impossible, is likely inflated, and around five thousand would likely be a more accurate figure. Additionally, it describes his galleys as pentekonters, fairly large boats for the period, measuring somewhere around one hundred feet in length; although, it is likely that part of his fleet was comprised of triantakonters (shorter variants of the pentekonters) and various merchant ships.

Past the Pillars

Having departed from Carthage, Hanno first sailed his enormous fleet about 900 nautical miles to Gadir (modern Cadiz, Spain), another Punic colony that possessed a monopoly on Atlantic trade, leading a strong union of former Punic colonies, developing and controlling the Atlantic trade from the port of Arambys (Morocco) in the south to the legendary Cassiterides (speculated to be the Cornish peninsula in England) in the north. After having sufficiently cowed Carthage’s rivals in Gadir, Hanno traveled southward for two days before stopping to found his first colony which would be named Thymiaterion.

North African Forest Elephants

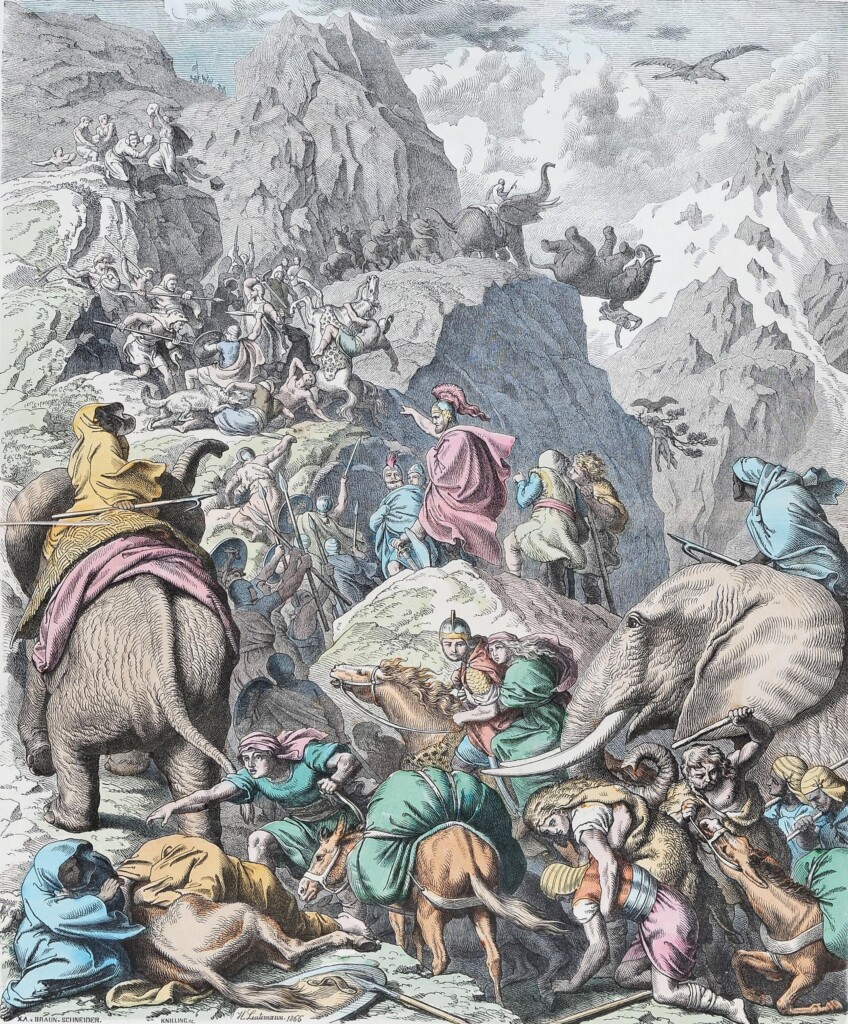

Hanno notes that the surrounding lands housed elephants. While the region is almost entirely devoid of elephants today, it was once roamed by herds of the now-extinct North African Forest Elephant. These elephants would be employed by Numidian, Ptolemaic, Seleucid, Kushite, and Egyptian armies, acting as premodern equivalents of tanks. They became staples of gladiatorial games during the Imperial Period but would become extinct by the late 300s AD. In their heyday, the Carthaginians would use elephants to great effect, particularly in their Sicilian campaigns and most famously when General Hannibal Barca crossed the Alps with thirty-seven elephants. However, Hannibal’s elephant (Surus) was likely a larger Syrian elephant.

Divine Duty

After departing Thymiaterion, Hanno’s next order of business was to embellish Soloeis, which was already housing a Punic population. To secure divine favor, Hanno funded the construction of a temple dedicated to the personification of the sea, “Yamm,” to be built in Soloeis.

Later visitors were clearly impressed by the Temple of Yamm as the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax declares that “of all Libya [Soloeis] is the most famous and holiest country.” The craftsmanship of the altar was so ornate that later Greek visitors declared that it must be the work of Daedalus, the legendary inventor who supposedly built the Minotaur’s Labyrinth at Knossos and constructed functional wings.

Colonizing the Coast

Having made his peace with the gods, Hanno continued down the Mauritanian coast, fortifying and expanding existing Punic outposts, depositing colonists in succession at Karikon Teichos, Gytte, Akra, Melisa, and Arambys.

The last of these colonies, which Hanno named Arambys would prove to be extremely lucrative. Arambys was in close proximity to an Atlantic island called Mogador, which provided the continental coast with protection from violent maritime winds, creating ideal conditions for a safe harbor. Unlike Kerne (a colony that we’ll examine later), Arambys remained under Phonecian control for centuries with archeologists finding many of their goods and storage devices. Despite its incredible positioning, Arambys’ most valuable asset was its abundance of murex and purpura shells, which could be found just off its shore. In modern times purple dye can be easily manufactured, but the same was not true in classical antiquity. It could only be produced from the mucus of some varieties of sea snails and the process was incredibly labor-intensive.

Tyrian Purple

Laborers would create dye by periodically jabbing the snails with a rod, prompting them to secrete a film which would then be collected in vats. Historian David Jacoby estimated that it would take the combined secretions produced by twelve thousand snails to dye the lining of an article of clothing. Dying an entire toga was estimated to take a quarter of a million snails. For this reason, only the very wealthiest could afford it, and the color purple became associated with royalty. The process of producing purple was a trade secret at this time, potentially explaining the origin of Phonecia’s name (land of purple). The most common shade of purple was called Tyrian Purple, named after Tyre, the foremost Phonecian city.

“Purple vats had to be outside the city walls [of Tyre] because no one could live next to the horrible smell made by rotten shellfish soaking in [ammonia] mixed with wood ash and water. Even the clothes that had been dyed with them had a distinctive odor of fish and sea. The historian Pliny called it ‘offensive,’ but for other Romans, it was the smell of money.” – Victoria Finlay

The End of the Earth

Next, Hanno expanded the Phoenician trading post of Aggadir into a proper settlement, depositing a significant quantity of colonists there. Aggadir sat at the very edge of the known world, functioning as a convergence point for all sorts of strange people and stories. Aggadir’s placement would eventually allow it to generate enormous quantities of wealth. Native tribesmen would venture to its markets and unload their goods, unaware of their true value. Their profits would sail north, past Arambys and into the wealthy Circle of Gadir (a mercantile league of Occidental Punic cities), crossing the twin Pillars of Melqart before dispersing into the wider Mediterranean. Beyond Aggadir laid only disconcerting legends and the dreams of explorers.

The Lixitae

While exploring the area adjacent to Aggadir, Hanno encountered a friendly people called the Lixitae, living in a fertile valley between a mountain range and the River Lixos (the Dra’a River in Southern Morocco). After discovering that some of the Lixitae had learned Phoenician from Aggadiran traders, Hanno befriended them and invited a number aboard his flagship to serve as translators. While their capacity as intermediaries degraded sharply as the fleet progressed further south, their skills as guides made these Lixitae an invaluable resource.

Kerne – The Last Habitation

Eventually, the fleet came across an island that they called Chernah and the Greek scribes knew as Kerne. Chernah means something along the lines of final settlement or last habitation. Its name would prove apt as it was to be the final colony founded by Hanno. While most of Hanno’s previous “colonies” had previously housed a Punic presence, we have no mention of Kerne or any of the lands south prior to the voyage of Hanno. Previously, I suggested that Kerne’s time under Phonecian control would be short-lived now, I shall take a brief aside to examine how we know this. Kerne next surfaces in the historical record in the middle of the 4th century BC in the periplus of Pseudo-Scylax.

Pseudo-Scylax describes that the coast of Kerne was filled with prickly seaweed and debris which prevented large merchant ships like the pentekonters Hanno used from docking on the island. Undeterred, later Phoenician merchants approaching Kerne would disembark from their primary vessels and load their goods onto smaller boats which they took to the island. The Phoenicians would trade goods from the Mediterranean with the natives in exchange for exotic animal hides. Pseudo-Scylax rather outlandishly describes the inhabitants of Kerne as the tallest of men, claiming that some reached heights of five cubits (about 7.5ft). He also matter of factly states that the tribe was ruled by the tallest among them. It is unlikely that Kerne housed any permanent population during this period and the natives that Pseudo-Scylax mentions likely lived on the mainland in modern Mauritania.

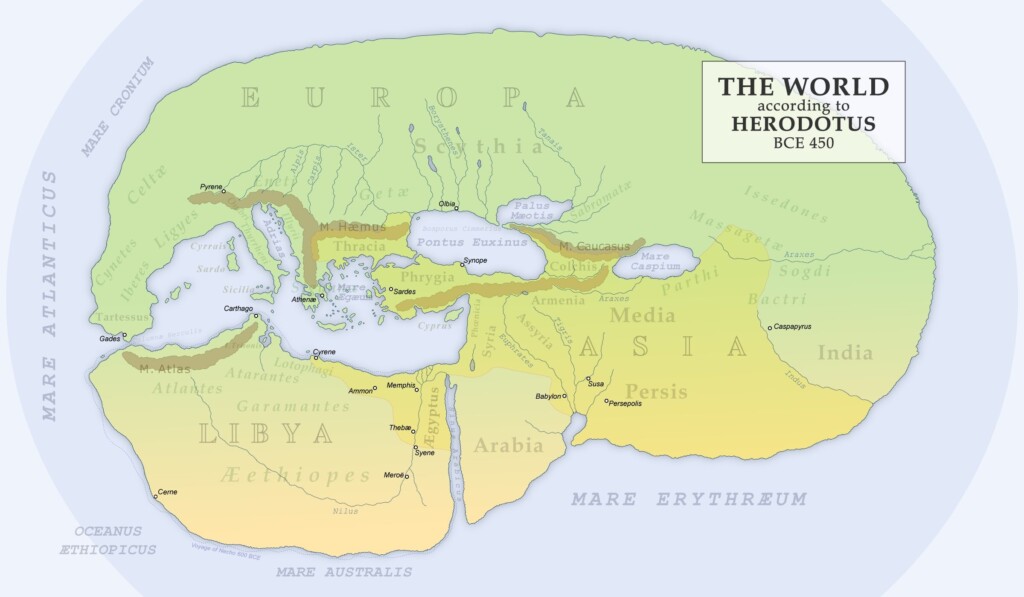

The conditions became increasingly inhospitable as the fleet ventured south of Kerne. For a time, they traveled up the River Chremetes (liklely the Senegal River) which was believed by the Greeks to be the Nile’s source, encountering hippopotami and crocodiles as they sailed. In what appears to be a gold trade gone wrong, Hanno’s ships were pelted by stones flung from natives and were forced to return to Kerne. The identification of the Chremetes as being a possible source of the Nile was due to the belief at the time that crocodiles only inhabited the Nile. The phrase used by the the Greeks to refer to crocodiles “ho krokódilos tou potamoú” literally meant “lizard of the river” with river understood to mean the Nile.

Later merchants would evidently have more success trading with the natives of the region than Hanno did. In his Histories, Herodotus describes the peculiar manner in which the Carthaginians traded with people whom Herodotus refers to as Libyans. According to him, Carthaginians would bring goods to the shore, light a signal fire and retreat to their ships. The Libyans and the natives would leave gold by the items. Traders would come back, asses how much the natives were offering and if the gold was deemed sufficient they would take it with their business being concluded. “In this transaction, it is said, neither party defrauds the other: the Carthaginians do not touch the gold until it equals the value of their cargo, nor do the people touch the cargo until the sailors have taken the gold” (Herodotus, The Histories, Book 4, Chapter 196).

Into the Unknown

Past this point, Hanno’s Lixitae translators could no longer comprehend the speech of the locals. Historians postulate that this was because the Lixitae could understand the various mutually intelligible Mande languages, but that by this point, the common tongue belonged to the Kru branch of the Nigeria-Congo language family.

Hanno’s account becomes more confused after his translators fail him. He writes of passing by a promontory he calls the Horn of the West. In this region the explorers were evidently terrified by native’s “horns, cymbals, drums plus voices” causing the fleet to fleet” with great speed in great fear” and “at night [they] saw all was aflame.” Pedro de Sintra, the Portuguese explorer who “discovered” Sierra Leone, left similar accounts of great fires and strange noises coming from the shore. Although neither explorer knew it at the time, these tremendous fires were the product of slash and burn agriculture which is still popular in Sierra Leone in the modern day.

Nine days’ sail from the Horn of the South, Hanno encountered “a very high mountain was seen from which spewed great flames” which he called the Seat of the Gods. There is some debate about the identity of this volcano, but Mount Cameroon is the most likely candidate, providing a definitive point along the coast of Africa which can be used to mark Hanno’s progress.

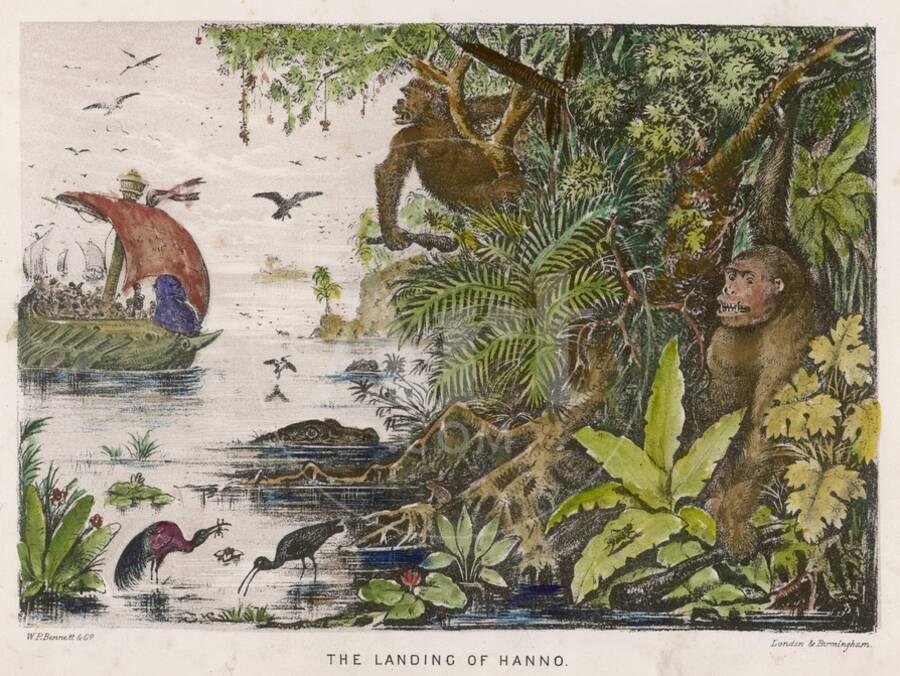

Gorillae

The final line of Hanno’s Periplus makes brief mention of an encounter with some form of haired Great Ape which new interpreters evidently brought on since the Lixitae became obsolete termed as “gorillae.” Its unclear whether these “gorillae” were what we now know as gorillas or if they were some other species of primate. If indeed these were gorillas, than Hanno’s account marks the only western recording of their definitive existence until French explorer Paul Du Chaillu encountered them in the 1850s and brought deceased specimens back to Europe for study. Hanno too brought evidence of his encounter home, skinning three gorillae. He would hang their hides in the Temple of Tanit, one of the most important in Carthage, and they presumably remained there until the destruction of Carthage in 146 BC. Surviving accounts of these strange skins in Carthage provide proof that the above events occurred and were not merely later fabrications. The periplus abruptly ends here with the author declaring “we did not sail any further, because our provisions were running short.”