Redeemer. Reformer. Restorer. These words describe one of the last great Roman emperors – Julius Valerius Maiorianus, otherwise known as Majorian. The soon-to-be-legendary figure was born into the Roman Empire during a time of unprecedented crisis. By the 5th Century AD, Rome was on its deathbed, plagued by civil wars, hyperinflation of the currency, foreign invasions, and depopulation. Long gone was the Pax Romana, a period of nearly 200 years that saw massive economic, military, and population growth for the Roman Empire. Throughout the 3rd Century, Rome was racked by incompetent emperors, civil war, plagues, and external barbarian invasions. Foreign tribes defeated the Romans on the field of battle, and sacked Rome, the capital of the Empire, twice. Rome’s finances were in shambles, as its currency was devalued to the point of near worthlessness. The internal trading systems, which for so long were vital to the Roman economy, became untenable as the countryside became unsafe for merchants.

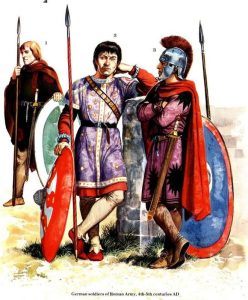

The Roman aristocracy ran massive tenant farm plantations, growing olives, grapes, wheat, and various fruits that required thousands of laborers to cultivate. As a result, Rome’s income gap became polarizing between the hundreds of rich landlords throughout the countryside and the poor tenant farmers that worked the fields. Because of the financial power of the aristocracy, Rome’s elite forbade the emperors from recruiting from the Italian peninsula, where their workers lived as this would cut into their profits. So, Roman Emperors turned to barbarian foreigners to fight their wars. These barbarian warriors were disloyal, had no connections to Roman culture, and were poorly disciplined. As a result, Rome’s military which was once considered the most disciplined, well-trained, and efficient army in the world became notoriously unreliable.

By the 5th century, the Roman Empire, which had once stretched from Britain to Syria, was divided into two separate states. These two empires were the Western Roman Empire, consisting of France (then called Gaul), the Iberian Peninsula (called Hispania by the Romans), North Africa, and Italy, and the Eastern Roman Empire, consisting of Greece, Anatolia, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt. Both states often fought against each other, continuously destabilizing the realm.

In the year 457 AD, the crisis the Empire had been faced with had grown worse. Rome was more militarily, politically, and economically weak than ever. But for a brief period of 4 years, Rome would see a resurgence under the brilliant emperor Majorian, an emperor who has largely been forgotten in history but deserves credit as the restorer of the dying empire.

Majorian’s Early Life

Julius Valerius Maiorianus was born in an unknown location sometime during 420 AD. His family was of Roman heritage, and Majorian was described as possessing fair hair. Like much of Rome’s population by the 5th Century AD, Majorian was a Christian. Much of what we know about Majorian comes from the Gallo-Roman historian Sidonius Apollinaris, who wrote extensively about the future Roman Emperor. Sidonius recounts how Majorian, like his father and grandfather before him, became a military commander in the Roman Army. In 447, he marched into Gaul with his commander, Flavius Aetius, to quell rebellions against the empire. Whilst on a campaign against the Germanic Frankish tribe, Majorian displayed his personal bravery on the field of battle as he fought on a bridge against an enemy attack, eventually leading an attack that routed the Frankish army.

Sidonius would write: “There was a narrow passage at the junction of two ways, and a road crossed both the village of Helena… and the river. [Aetius] was posted at the crossroads while Majorian warred as a mounted man close to the bridge itself.”

Alluding to his later role as Western Roman Emperor, Sidonius writes “[Majorian] fought with the authority of a Master but the destiny of an Emperor.”

Flavius Aetius, Majorian’s commander, was born somewhere in the Balkans and was of Illyrian ancestry. Rapidly rising to the rank of Magister Militum (which was essentially the overall commander of all Roman armies) in the Western Roman Empire, Aetius reconquered much of Gaul from barbarian tribes and defeated a Hunnic invasion led by the infamous Atilla the Hun. Under such a talented military officer, Majorian likely learned much from Aetius and it would shape his capabilities as a military commander in his future reign.

It was during this time that Majorian gained valuable experience not only commanding troops but also managing the logistics and operations of a massive Roman field army. He likely participated in or commanded battles against a variety of Rome’s foes, from the Germanic Visigoths to the nomadic Hunnic tribes. It was also during this time that Majorian became acquainted with several Roman commanders, many of whom were of barbarian origin. One of these Roman officers was Ricimer, and the two formed a close bond in war.

By 450, Majorian had become an experienced commander and lieutenant to Aetius, and the Roman emperor Valentinian the III began to see Majorian as a possible commander for all Roman armies. It is here where Majorian’s ancestry comes into play, as unlike Aetius (and most other Roman military commanders during this period) Majorian was a full-blooded Roman, and thus was seen in a better light by Valentinian than most other army commanders. Valentinian considered marrying his daughter to Majorian, but Aetius interceded and privately confronted Majorian. Majorian’s commander was seeking to marry his own son into the Imperial royal family and saw the upstart commander as a possible threat to his aspirations for power. In unknown circumstances, Majorian left the army and lived out on his country estate for 4 years, isolated from the politics of the empire.

Aetius, despite pushing Majorian out of the hand of Valentinian, was faced with attacks of his own. Valentinian, fearing Aetius’ rising influence, had him assassinated in 454. Fearing that Aetius’ barbarian troops would rebel, Valentinian called Majorian to quell any dissent in the army. Because of Majorian’s experience campaigning with these troops, he was able to convince them to switch their loyalties to him. But Valentinian was then killed by some of Aetius’ former officers, and a Roman aristocrat, Petronius Maximus, took to the throne. Maximus was an incapable ruler and was killed when the Vandals, a tribe who conquered North Africa from the Romans in 429, sacked Rome in 455. Majorian and another one of Aetius’ former deputies, the Germanic Ricimer, then captured the new Roman emperor Avitus. Majorian killed Avitus and became the most powerful man in Italy by 457.

Proclamation as Emperor and Civil Affairs

Whilst Majorian consolidated his power in Italy, a Germanic invasion was defeated by his commander Burco, and the population rallied around the war hero Majorian as they proclaimed him Augustus, the Latin term for the emperor. Majorian had little time to rest, as the Vandals returned to Italy in the summer of 457. But Majorian defeated them in battle and set out about constructing a new Roman navy to combat the repeated naval assaults of the Vandals. Creating a navy from scratch was a massive logistical undertaking, especially for an empire virtually bankrupt. But Majorian persevered and built two fleets, one in the Mediterranean Sea and the other in the Adriatic Sea. Sidonius commented that Majorian utilized wood from the Apennine Mountains which are located in central Italy to build the fleets. As the historian recollects: “Meanwhile [Majorian] built on the two shores fleets for the upper and lower sea. Down into the water falls every forest of the Apennines.”

Legal and Financial Reform

Majorian created two new laws, the De reddito iure armorum (“On the Return of the Right to Bear Arms”), and the De aurigis et seditiosis (“Concerning Charioteers and Seditious Persons”). The former of these laws sought to allow the population to form militias for the common defense, and the latter sought to quell public disturbances in the aftermath of chariot racing. Majorian, realizing that the empire needed a strong fiscal policy to recover economically and to pay for further reconquests, reformed the coinage and tax systems. He minted new gold coins with a stable percentage of gold, making the Roman currency a stable form of financial transaction. The emperor reformed the tax collection system, which was corrupt and often alienated the local population. Majorian enacted a law that forced tax collectors to pay the imperial treasury for taxes not exacted and canceled all tax arrears, ingratiating himself with the local aristocracy and small landowners.

Majorian created a law creating a public magistrate office in major cities across Italy to represent the urban poor in legal disputes, as well as forbidding tax collectors from fleeing their posts. To raise the declining birth rate of the empire, Majorian forbade women below the age of 40 from entering the clergy and dictated that wedding dowries be lowered to make marriage more financially attractive.

Finally, Majorian gave positions of power to influential Roman senators and aristocrats, raising his support among the elite. He made efforts to curtail their influence within the economy and limited their ability to purchase new lands for agriculture. The previous emperor, Avitus, had alienated the Italian aristocrats by appointing Gaulic elites to prominent government positions. Majorian maintained an equilibrium between the two groups by appointing Italians and Gauls in equal proportions to the administrative positions in the empire.

Majorian’s Protection of Rome’s Monuments

For centuries, Rome’s monuments, which served as a display of imperial power, were in physical decay. The empire had long since lost the ability to build new monuments and thus neglected buildings, arches, and statues that commemorated great Roman emperors, statesmen, and generals. By the 5th Century, Roman monuments were being harvested for building materials as the internal infrastructure of the state began to collapse. It became harder for quarries in the Balkans or Egypt to deliver their building materials due to foreign invasions and banditry, so the local citizens of Italy chipped away at the monuments in their cities for valuable marble, granite, or limestone.

Majorian, disgusted at the destruction of Roman culture, forbade anyone from defiling Rome’s monuments. The punishment for the destruction of memorials was harsh, as Sidonius states that anyone caught destroying the monuments would be flogged and have both hands amputated. Through such harsh measures, Majorian is one of the main reasons why so much of Rome’s history has been preserved to us in the present.

Majorian marches west

Majorian began to desire a reconquest of the lost territories in the Roman Empire. Refusing to go quietly into that good night, the experienced commander begin plans to reconquer massive territories like Gaul and Hispania. For decades, Roman authority in those regions had been deteriorating rapidly. Gerald E. Max, writing in the journal Historia: Journal of Ancient History, stated that “the dismemberment of the Empire was, at the outset of [Majorian’s] reign, all but an accomplished fact. Federate and sovereign states, long-established or nascent, of dubious loyalty or actively hostile, infested the once far-reaching and ordered dominions of the Pax Romana.”

Gaul, in modern-day France, was one such territory that had been in Roman hands for centuries. Ever since the Roman general Caesar had marched north across the Alps and conquered the region, it had been a developed and profitable part of the empire. Its infrastructure was well developed and it had large agricultural estates producing luxuries like grapes or olives and bustling cities producing manufactured goods like glass or pottery. This gem of the Western Roman Empire had revolted against Majorian upon his coronation as emperor because of his assassination of Avitus. Majorian, determined to rekindle the embers of the Roman Empire, began to recruit local Italian and foreign troops. He crossed the Alps in 458 and began his campaign in Gaul.

Majorian elected to leave Ricimer, his loyal companion who had fought with Majorian for years, behind in Italy to maintain control over the peninsula. Whilst his comrade was gone, Ricimer took several steps to increase his political power in Italy. Majorian took with him Aegidius and Nepotianus, two capable barbarian generals, and set out to subjugate the Visigoths, a Germanic tribe that had settled in western France. The details of this campaign are scant, but Sidonius says that Majorian defeated the Visigoths at the Battle of Arelate. In the aftermath of the victory, Majorian demanded that the Visigoths give him military-age men to fight in the Imperial army in exchange for peace. Majorian then turned east and defeated the Burgundians, another tribe that had settled in Gaul during the 5th century.

It was during this time that Majorian befriended and recruited the services of Sidonius Apollinaris, the son-in-law of the former emperor Avitus. Sidonius had reason to distrust or hate Majorian, as the latter had killed the poet’s father-in-law. But Majorian befriended Sidonius as the two shared a passion for literature and history. Sidonius wrote a panegyric (a text praising another person) in Majorian’s honor, and Majorian constructed a statue of Sidonius in Rome. Scottish classicist notes about Sidonius’s writings: “Whatever one may think about their style and diction, the letters of Sidonius are an invaluable source of information on many aspects of the life of his time.”

To replenish military casualties and to more easily conquer territory, Majorian forced the conquered Visigoths and Burgundians to pledge themselves as Foederati, or federates, to the Roman Empire. When foreign tribes entered Roman territory in the previous decades, Roman governors or emperors would be unable to resist due to the crisis facing the empire. To avoid conflict and destruction of the provinces by hordes of raiding tribes, the Romans offered the invaders land in exchange for promises of military support. Thus the foederati system was created, turning much of Rome’s territories into autonomous barbarian-controlled regions. The effects of this system impacted the Western Empire the most, and Rome effectively turned into an ethnic confederation of barbarian foederati and pockets of Roman administered territory, with Italy as its hegemon.

Although much of Gaul had sided against Majorian when he took the throne, Majorian refused to punish the local aristocrats. Instead, he requested their military and financial aid and treated them well and with respect. By doing this, Majorian avoided the financial burden of committing to a years-long conquest of Gaul and instead won over much of the population with his generosity. Aegidius was appointed as military governor of Gaul, and being of partial Gaulic descent himself he was a good choice for the position to coordinate with the local Gaulic population.

Turning South to Hispania

In 459, Majorian turned his eager eyes south to the Iberian Peninsula. Known to the Romans as Gaul, this peninsula had also been a Roman province for centuries. But in 456, the Visigoths had conquered the peninsula from the Romans and Imperial authority in the region degraded substantially. After his conquest of Gaul, the Roman emperor led his army across the Pyrenees Mountains separating the two provinces. The Vandal, Visigothic, and Suebi tribes had invaded the regions and now ruled large parts of the region as their own. Wishing to see the military strength of the opposing Vandal forces, Majorian dyed his hair and personally visited the Vandal King Genseric to view how prepared the Vandals were for war.

Satisfied that victory was attainable, Majorian divided his army into two, sending Nepotanius west to defeat the Suebi and leading the remainder of the army south to defeat the Vandals. Both campaigns were successful and Hispania was successfully reconquered by 460.

Invasion of North Africa

During this time, Majorian sought to reconquer North Africa, a rich province that once was the breadbasket of the Roman Empire.

The province had fallen to the Vandals years before Majorian’s rise to power, and they had launched several seaborne piracy campaigns across the Mediterranean. Vandal sea pirates had destroyed Roman trading, ravaged the coastal areas of the empire, and sacked the city of Rome itself. Majorian had temporarily halted the Vandal tide by constructing the two Roman fleets, but this was purely a defensive measure. The Vandals would only be vanquished by a direct invasion from a Roman army based in Hispania.

The Vandal King Genseric, who had been hearing reports of the new Roman ruler vanquishing every opponent he faced on the battlefield, offered Majorian concessions to avoid a direct attack. But Majorian wanted nothing short of a complete occupation of the rich North African province, and so utilized his naval fleets to amass 300 ships in eastern Hispania, together with a large Roman army to invade North Africa. Majorian ordered Marcellinus, a rogue Roman commander in the Balkans, to move his army to retake Sicily to prepare for a two-pronged invasion of Africa. Genseric then ravaged his own territory in Africa in an attempt to deny Majorian’s army resources once it landed in his kingdom. But such an invasion never came. As Sidonius writes:

“While Majorian was campaigning in the province of Carthaginiensis the Vandals destroyed, through traitors, ships that he was preparing for himself for a crossing against the Vandals from the shore of Carthaginiensis. Majorian, frustrated in this manner from his intention, returned to Italy.”

Betrayal and Death

Such a devastating blow, achieved through deceit and betrayal, stung Majorian deeply. His fleet had largely been destroyed, and his planned conquest of North Africa had failed. The weary commander disbanded his foreign units and returned to Italy, where he planned to enact further reforms. With just his Italian troops remaining, Majorian’s army shrunk dramatically in size. As Majorian neared the city of Tortona in Northern Italy in the year 461, he encountered his old friend Ricimer, but with a large body of Germanic troops. Majorian was captured by Ricimer and was forced to voluntarily abdicate the Roman imperial position. He was then tortured for 5 days until he was beheaded and his body was dumped into a nearby river. Majorian had ruled for just 4 years and was 41 years old at the time of his betrayal.

Whilst Majorian had been off rekindling the flame that was Rome, Ricimer had been scheming in the shadows in Italy. The traitorous commander plotted with Roman aristocrats who were angered at Majorian’s reforms, eventually conspiring to place a loyal senator on the imperial throne as a puppet. With the backing of the Italian aristocracy, Ricimer set his plan in motion and crowned Libius Severus as the new Western Roman Emperor. But Ricimer’s plan didn’t go well from the start. Majorian’s loyal deputies, including Aegidius in Gaul, Nepotianius in Hispania, and Marcellinus in the Balkans, refused to acknowledge the new puppet emperor and rose in revolt. Ricimer would continue to act as kingmaker in Italy but would die in 472 AD from a stroke. The Western Roman Empire would fall 16 years after Majorian’s death as a series of civil wars and barbarian invasions toppled the eternal city.

Assessment

Majorian, in an attempt to fully restore the past glory of the Roman Empire, restored much of Rome’s economic and military power. By reforming the tax collection system, the Western Roman Empire was capable of constructing two new fleets and maintaining a large army in the field for years at a time. Majorian’s policies for protecting Rome’s monuments allowed for centuries of history to be preserved for us in the present. And his civil policies, aimed at lowering the financial burden befalling the average Roman citizen, created a brief era of stability in Italy. His military reconquests in Gaul and Hispania subdued barbarian invasions and brought new prestige to the dying state.

However, either because of flaws in his strategy or his tragically short reign, Majorian was not entirely successful. Much of the lands Majorian retook from foreign tribes lacked a permanent Roman administration. In Gaul, the Roman emperor forced defeated tribes to give him manpower for wars and then left the province in the hands of Aegidius. Aegidius ran the province as his own private fiefdom, and there there was no construction projects or any signs of Roman military units being stationed in the region. In Spain, Majorian also failed to bring lasting change as the Germanic Suebi and Visigoths controlled much of the interior of the Iberian peninsula. No tax collectors dared go beyond Italy for fear of attack by brigands or Germanic tribes. Most of Majorian’s policies affected just Italy, with the rest of his newly reforged Empire being essentially a tribal confederation led by their Italian hegemon.

Majorian also failed to break the power of Rome’s senatorial aristocracy, who withheld from the state the vital manpower needed to reconquer its lost lands. The elite still ran their massive plantations and refused to allow their laborers to be conscripted into the Roman armies. Because of this failure to reign in the rich landowners, Majorian was forced to rely on foreign barbarian auxiliaries to fight his wars. When he dismissed these barbarian units, he was vulnerable to the schemes of Ricimer.

But since Majorian was assassinated just 4 years into his reign, it remains a mystery whether Majorian would have been able to fully assimilate the breakaway provinces into the Western Roman Empire. If Majorian had been able to fully implement his reforms, increasing Rome’s manpower, and tax revenue, and rebuilding the ravaged cities of Italy, it’s possible he or his successors would be able to make Rome a great power once more.

Nevertheless, Majorian’s restoration of the collapsing empire remains a legendary example of determination and leadership. To go from possessing a rump state in Italy to expanding his territory threefold remains an impressive feat in the annals of Roman history. Other than the example of espionage carried out by Genseric in Hispania, Majorian never suffered a military defeat. It appears that although Majorian’s brilliance gave the empire years more in its lifetime, Rome was in such a decaying state that it needed an almost mythical figure to pull it from the brink of collapse. Unfortunately, Majorian lacked such divine qualities.

Majorian remains one of the least known Roman emperors. The only contemporary accounts we have for him are from Sidonius, and the only physical proof we have of his existence is some coins and surviving law codes. In lists of the greatest Roman emperors, Majorian usually remains out of the picture. But I hope this article had shed some light on why he deserves to be remembered as an admirable figure, desperate to reverse the course of decline in a nation that once had a claim to greatness.

As Steward Oost states in his journal Aetius and Majorian:

“Majorian (457-61) was the last West Roman Emperor of any real importance. Energetic and able as he was, however, he eventually proved powerless before the hard fact that effective command of the military force of the Western Empire had irretrievably slipped from the hands of the government into the control of the barbarian master of the soldiers in this case, and until his death in 472, Ricimer.”

Author Gerald E. Max describes Majorian’s reign:

“Among the last emperors of the Roman West, Julius Valerius Majorianus was a singular anomaly; a ruler of strong will, energy, and independence. To his panegyrist and admirer Sidonius Apollinaris, whose name the age itself might bear, he was Scipio Africanus and Trajan reincarnate. Born, however, in the very worst of times, he was, as the historian, Gibbon suggested, a hero in an age of iron who longed for a golden age past. As Emperor, he reigned under exceptional duress to fulfill the object of his longing, making a maximum effort to reverse the irreversible process of decline the Empire had been undergoing for a century.”

British writer Edward Gibbons, who in the 1700s wrote a now-famous book titled The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, commented that Majorian “presents the welcome discovery of a great and heroic character, such as sometimes arise in a degenerate age to vindicate the honor of the human species.”