If you listened to the chorus of modern society today, the Latin language seems too archaic, a fossil of a bygone age of Caesars, gladiators, and crimson-colored Roman legions marching on the Appian Way, to be of any use. “It’s a dead language,” many will quip, “I don’t see the point in studying it.” But these critics couldn’t be any farther from the truth.

In this article, I will uncover the historical background of the Latin language, its cultural values embedded throughout our American society, and the continued relevance it possesses. To assist in the writing of this article, I interviewed Jesuit Latin language teachers Ms. Laura Hudec and Ms. Vanessa Jones about the utility of this language. Believe me, it does not end at just SAT vocabulary words.

Interview with Ms. Hudec

Ms. Hudec is one of two Latin teachers at Jesuit. This was her first academic year of teaching at Jesuit College Preparatory School, and she has assisted Ms. Jones in running Jesuit’s Latin Club, as well as facilitating the Junior Classical League competition hosted at Jesuit in February.

When and where did Latin emerge as a language?

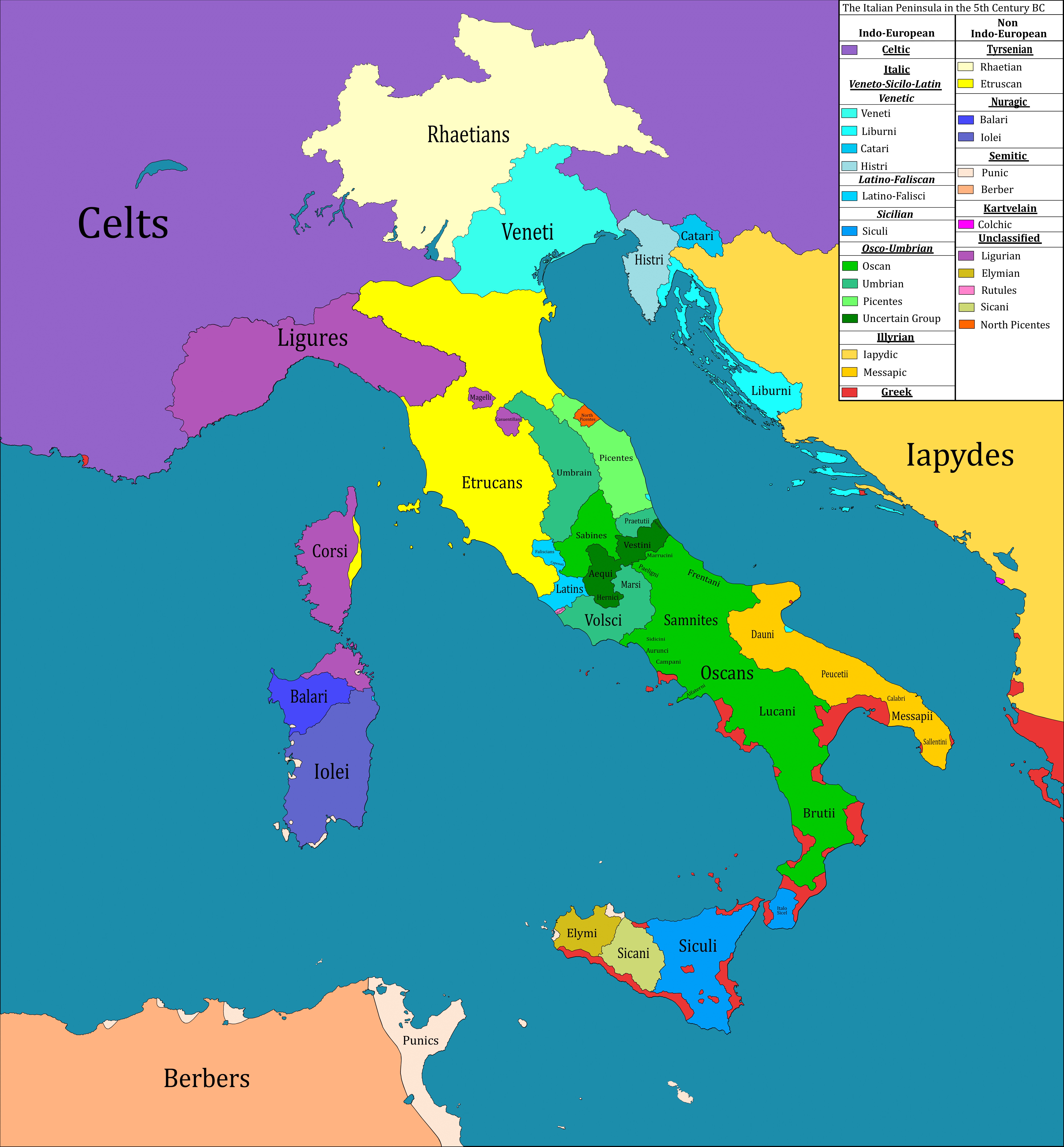

In the peninsula of Italy, before there was anything Roman, the Greeks had established cities and colonies in the southern tip of the peninsula, and the north was a grouping of Italian tribes and peoples. According to Roman mythology, near the center of the peninsula, Romulus founded Rome on these 7 hills which it was basically a swamp.

The language of Latin came from Rome, and there are a lot of connections, grammatically, with Greek, even if the writing style is different.

When Rome expanded and conquered these Italian communities, how did their native languages change?

Languages always influence each other through trade, war, and any sort of interaction. We know that many of these languages that preexisted Latin, such as Etruscan, Oscan, or Greek, influenced Latin heavily. It’s never that a language is lost, it is just that a culture is lost. And these cultures were absorbed, because that’s what the Romans were good at – assimilation. For the Italian people, resistance was futile, so to say.

The Romans would do this with religions and other cultural items throughout the world. People began to accept these changes and adopted them.

Throughout Rome’s expansion in the Mediterranean, that was how Latin became more well-known throughout the world?

That’s how the language spread throughout the Mediterranean, but it was localized to an extent. That’s how we get languages like Spanish, French, and Italian. All of the Romance languages came off of Latin, whilst having their own local flavors.

Latin was a trade language, but it wasn’t the dominant language across the Mediterranean even during the Roman Empire. It was a trade language, certainly, and a language of the elite, but most people outside of Italy without Roman heritage spoke their own languages.

In Mary Beard’s book SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome, she writes how the language of Latin could be separated into two dialects: Vulgar Latin, spoken by the common people, and Classical Latin, spoken by the elites. Which of the two continued on throughout the Church?

The simplified version of Latin did. The Nova Vulgate, or the Latin translation of the Bible, is written in Vulgar Latin. When I mean simplified, a lot of the grammar and pronunciation were just blunt and efficient as possible, not trying to be all high as a speaker of Classical Latin would. Now some of the biblical letters, such as the Letters of Paul, were written in a more classical way, but for the most part, the Church stuck to the Vulgar Latin. And it is very difficult to translate these works of scripture from Hebrew and Greek into Latin because its hard to get the meaning across.

If there was no Latin language, how different would European languages be today?

“It is the nature of humankind to conquer, and whoever it is that wins in these wars, their languages win.” – Mrs. Hudec

If you start to look at how over time things move based on colonialism, you see how languages move over time. It’s not a language thing, it’s a part of the people and culture and what they do.

When Rome fell, and the ‘barbarians’ took over, how did they interact with Latin?

We have records of historians from that time, who say that these new Germanic invaders did not want to destroy all the preexisting Roman society. People often talk about the “Sack of Rome” but that is overstated, most of these ‘invaders’ just realized that the systems they inherited from the Romans were good enough, and they felt there was no need to destroy them.

The same occurred with the language. Latin has already been established and spread everywhere, and why would the new rulers bring new cultural values in when the current system worked so well? These invaders were pretty smart, these ‘barbarians’, when they saw institutions that worked so well, and they were just focused on having power and influence, and they realized Latin had that influence.

When these new peoples migrated in, did the foreign languages they spoke that interacted with the local Latin language combine to create the Romance languages of Europe?

Absolutely, the different ethnic groups that conquered each chunk of the former Roman Empire had to combine with the different local peoples, who despite all utilizing Latin still possessed their own regional dialects or cultural values. That’s how you get Spanish, French, etc.

With the fall of the Roman Empire, when did the Latin language die out amongst the local peoples?

Well, it was a slow process, but because Latin was the language of the Church, it was maintained throughout Europe for centuries. But people began to realize that their own cultural values and new mixing with these ethnic groups allowed them to create new works of literature, and new works of art, and that helped facilitate the divergence of new languages from Latin.

It’s really interesting about the relationship between Latin and the Catholic Church, people have analyzed how the influence of Latin depends on the influence of the Church, and so during times of papal crisis, such as during the schism with the Pope in Rome and the Antipope in Avignon, Latin wanes, and grows in influence when the Church grows in power.

Did the Catholic Church adopt the Latin language because of its universal application and familiarity across Europe?

Until Vatican II, Latin was the official language of the Church, and it was always the language of scholars who were closely tied to the Church. Even to this day, it is still the language of scholars and researchers. If you go into a room with people who speak different languages you could still communicate a little bit just by relying on Latin or the Romance languages because of their shared roots.

When Latin was perpetuated by the Church, did upper echelons of society retain the language? Was Latin a sign of culture or status?

With people throughout history, they knew that Latin was already a sufficiently existing language, so they kept utilizing it. And Church officials, especially popes, retained a high standard of knowledge of Latin, such as Pope John Paul II, or Pope Benedict XVI. The Church has retained parts of the Mass in Latin, and it will remain the language of the Church for a long time.

A lot of people would say that the Latin language is just dead and not relevant outside of the Church.

Well, a dead language is just a language that is not changing, not a language that has no speakers. Languages like Spanish and English have changes to their conjugations or sentence structures because they are constantly changing – Latin not so much. A dead language does not change, an extinct language is a language that has no present speakers or scholars.

There is a danger for the Church that once you declare that Latin is irrelevant, then you lose everything from the Church’s Sacred Tradition and from the Church Fathers. The minute you forgo Latin, you forgo Augustine, Aquinas, and everybody from the classical schools of thought.

“The Church can’t forsake Latin, it’s their history, their heritage. And Latin cannot survive without the Church.” – Mrs. Hudec

Interview with Ms. Jones

Next, I talked with Ms. Jones, who also teaches Latin and assists in organizing the Jesuit Junior Classical League, about the Junior Classical League. Also known as JCL, the extracurricular group focuses on the development of its member’s proficiencies in a wide genre of competitive activities related to the Roman or Greek language, history, art, or culture. Students select which genre to compete in, and may compete at regional, state, or national levels to earn scholarships or academic awards.

Ms. Jones, did you start the Junior Classical League when you arrived at Jesuit, or was it preexisting at Jesuit?

The Junior Classical League has existed for 70 years, it has sponsored regional, state, and national tournaments across the country, and Jesuit Dallas has historically participated in this activity.

What was the purpose of the Junior Classical League?

“To Pass on the Torch of Classical Civilization,” Ms. Hudec dramatically comments from across the hall. Ms. Jones laughs and then turns towards me.

“If we know one thing about the world, it’s that history repeats itself. It’s very important for us to be scholars of history, and to learn about other cultures, languages, and ways of life from other peoples.” – Mrs. Hudec

There’s a deeper appreciation for forms of literature when you can speak the original language – and the Junior Classical League can facilitate that.

And that includes the writing, speaking, and reading of Latin that the Junior Classical League offers competitions in?

Yes, the Junior Classical League offers all of those and even more. They have events for every type of interest, sports, costume contests, quiz bowl, and art, from educational posters created about the ancient world to a replica of the Trojan horse. Kids that are great at drawing, painting, trivia, ancient literature, or are just creative have opportunities awaiting them. There’s an event where you can create a board game that must be related to classical literature, and then you present this self-made game to judges at tournaments.

I found that kids that are drawn to Latin class are kids who are drawn to the arts, and kids who are drawn to band, singing, or theater. These activities allow them to exercise the intellectual talents they already have.

It seems a lot of the Junior Classical League events have to do with Latin and Greek culture.

It’s awesome because even if I can’t teach all these topics in regular Latin class, I can help kids hone their skills in these activities through the Junior Classical League. We have students who love history or Greek derivatives, and we have competitions for those. These kids get to read about things that they always like, but they also work on learning more about this topic so they can do better each year.

I had a Senior who never was an A+ student, and he still did JCL every year, and he won first place in the Roman life category at a competition. He would go back every year leading up to his final opportunity and review the questions he got wrong and right, and that allowed him to do so well that he got first place.

In these Latin Club meetings, how do you prepare the students for these tournaments?

One of the things that is great about JCL is that you can put as much into it as you want, or as little as you want. If a kid wants to win, and they are determined to win a state or national award, then they will put that work in. And it really doesn’t take that much effort or studying outside of class to get recognized for academic merit.

Since the pandemic happened, it was hard for the Latin club to do study groups, but since we are back in the normal swing of things, we are going to have some of the guys who are experts in certain topics lead groups who are competing in those areas. For example, we have a sophomore named Royce Szarzynski, who is excellent at Roman and Greek history, and we might make him a student leader in that category. Lucien Matula is really good at site recitation, which allows him to pass on this knowledge to younger students.

And I’ll be honest, I don’t know a ton about Greek history, but when the students are on their own, they can learn from other students, or from their own teachers.

I’ve heard that the Latin club will bring in guest speakers on certain topics, how often are they brought in, and what do you try to achieve from these presentations?

This isn’t something we’ve done before this year, because we hosted the regional JCL tournament last year and this year, we try to have as much knowledge coming in to help our kids learn as much as possible. We want to remember how much talent we have in this building, and we bring in guest speakers like Mr. Pointer, who can read Latin and is very experienced in ancient classical economies and political systems.

“What I love the most about JCL is how it can allow kids to show their academic talents to stand out in the crowd. It shows how well-rounded a student is, whether in their community or to college.” – Ms. Jones

I try to get all my Latin students to take JCL, and some kids think that it may not be for them, or that it’s too nerdy, but I always say that you don’t have to make this your whole personality. This is just to allow students to learn something new, to have them explore their passions, and attain cool new abilities that set them apart from the crowd.

Like Lucien Matula and his Greek poetic recitations.

Exactly.

Conclusion

Despite the Latin language trope as a dead language, my discussions with Ms. Hudec and Ms. Jones have proven anything but that. From its historical relevance as the foundation of many modern European languages to its continued heritage through the religious institutions of the Church, Latin has spread its roots throughout the world.

For Jesuit students who desire to learn more about Latin and the ancient world in an infinite number of ways, Jesuit’s Latin club offers a chance to connect with other like-minded and intellectually adventurous people. Whether it be a guest speaker lecturing on a niche historical topic, Ms. Hudec and Ms. Jones’ teaching of Latin in the classroom, or a student leader who happens to know a few things about ancient art, a member of the Junior Classical League is exposed to a wide variety of topics to dip their feet in.

Jesuit Dallas prides itself on fostering a wide variety of attributes that are grouped together as the “Profile of the Graduate.” Two of them in particular stand out as defining traits for those in the JCL. Intellectual competence is created through an introduction to numerous niche yet culturally relevant ideas or areas of competition. And being open to growth is attained through the process of leaping forward into the unknown, caring to explore for the sake of growing not only as a scholar but as a Jesuit man for others, as Icharus and Pytheas did so long ago.