In any ordinary museum, the visitors, allotted one visit in one day, tend to glance at the most prominent or famous pieces of art. In other cases, they tend to focus on pieces that “strike their fancy,” preferring particular styles of some works over others. However, the students of Jesuit receive four years, each about 180 days, to explore our collection as much as their time allows them to. Therefore, they experience the entire collection of the Jesuit Dallas Museum rather than a particular section. Knowing the massive amount of time given to Jesuit students, the museum spread out the art so that students could investigate all the pieces, and a piece worth investigating in the “corner” of the A hallway bears the name: Marcus Uzilevsky’s Royal Scepter Sonata.

Born in New York, New York in 1937, Marcus Uzilevsky lived with Polish and Russian immigrant parents. Early in his life, he found interest in drawing and carried it into a career, but later he left that path and learned the ways of the guitar. Under the alias “Rusty Evans,” Uzilevsky performed with Bob Dylan in the 60s. During his music career, he realized that art and music complement each other, prompting a move from The Big Apple to Marin County, California. “I want the art and the music I make to enhance each other,” he stated, “so that the total environment will have an uplifting effect.” Today in the uplifting environment of California, the renowned and acclaimed artist enjoys composing, drawing, and even calligraphy, all of which he incorporated into the Royal Scepter Sonata.

The piece being part of the Musical Offering display by the Jesuit Dallas Museum, one could argue that the museum included Royal Scepter Sonata, which the they permanently installed near the theater, to accompany the Jesuit Theater Performance Amadeus. The George Braque piece displays multiple musical instruments divided into pieces, which Mozart would have obviously conducted. Mozart would have used those instruments to play an intricate work of music, similar to the complex work in the Royal Scepter Sonata.

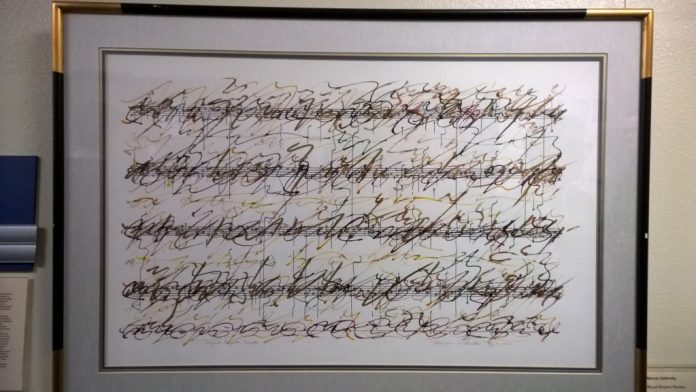

The Royal Scepter Sonata, according to Mrs. Elizabeth Hunt Blanc, represents an illusion of an old music score. However, one may or may not make it out as a music score at first, but rather a message inscribed in elaborate calligraphy. “It’s an interesting concept in the offering,” Jesuit Museum Director Elizabeth Hunt Blanc stated. “I find it interesting the different ways students would look at it.” She proved correct, for when Jesuit Band member Jose Torrealba ‘17 observed the piece, he mostly saw scribbled lines but understood its reasoning. “Music is abstract,” he said, “but it’s hard to express music without playing it.” Music, indeed, is abstract like a high percentage of art, and Uzilevsky’s work of art perfectly depicts a certain unity between the musician and the artist. On the other hand, perhaps Uzilevsky drew this painting to symbolize his sudden career change. The intense and arty calligraphy seemingly overshadows the light gray blotches, or notes, in the background. This thought represents Uzilevsky’s rediscovery of his interest of art while still displaying the remnant of his status as a musician. Either way, just as Mrs. Hunt Blanc said, we the student body elevate the interest in the art by providing unique opinions on all the pieces.

Often, society may question the usefulness of art, and this piece answers the question! Mrs. Hunt Blanc suggests that the piece should test the Jesuit Band and what they make of it. “The notes are faint, and because I read music, notes are the first thing I notice,” Torrealba claimed, proceeding to hum the notes.

Torrealba may notice the faint notes first, but would others read it as a piece of music, or would the artistic sides of their minds take over and alter their perspective of the composition? Nevertheless, the piece proves itself as a spectacular test of art interpretation skills.