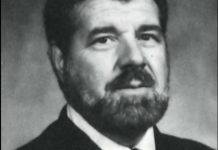

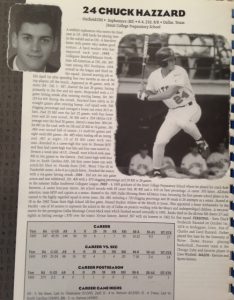

It all began for Chuck Hazzard ’93 in his crib, while he lay with his first baseball. Next was Little League. Then came high school baseball and with it Jesuit. He soon went on to the University of Florida where he would play in not one, but two College World Series, be named a First Team Freshman All-American, All-SEC Team Regular Season, All-Tournament Team for the SEC Tournament, All-Tournament Team for the NCAA Regional, and All-Tournament Team for the College World Series, and he was not even finished. He continued to stay with the game he loves as a volunteer coach at the University of Nevada Las Vegas and a graduate assistant at Pepperdine University. Hazzard has now started three of his own businesses, all of which have experienced their own successes. Yet, for Mr. Hazzard, most, if not all of these accomplishments pale in comparison to being inducted into the Jesuit Sports Hall of Fame.

“I guess it had something to do with my Dad growing up playing baseball and wanting me to follow in his footsteps,” says Hazzard about learning the game he has played since he was a child. Chuck Hazzard grew up in Connecticut, 45 minutes away from Yankee Stadium. It was in Connecticut where he would play Little League and develop his passion for baseball. “We had season tickets to the Yankees. My Dad always took me to the park. I just have always been really into baseball. It has always been a part of my life,” he said.

Hazzard’s interest in baseball, as well as his remarkable talent for the game hit their strides early on. During the time when Hazzard was first approached to play on one of the “better Little League teams in my town,” Little League was played only by ten, eleven, and twelve-year olds, primarily eleven and twelve-year olds, but that did not stop the town’s coaches from recruiting the nine-year old budding star. “When I was nine years old I was asked to play on one of the better Little League teams in our town. But my Dad told me that I needed to stay with my friends and I waited until I was ten to go play.” That period would go on to stand as the first instance that Hazzard recognized that his ability on the diamond may be extraordinary.

At the age of thirteen, Hazzard and his family moved to Plano, Texas, a move Hazzard credits as “being one of the most important moments in my baseball career.” The season prior to moving to Texas Hazzard played in 20 to 22 baseball games. After moving, he played around 50 baseball games and by the time he reached high school he was playing in 80 baseball games a year. “Baseball is a game that is meant to be played every day, so the more you play it the better you are going to get. I really think that … you known, who knows, I might have gone Division 1 staying in Connecticut, but I definitely became a top level, Division 1 player because of all the games and all the experiences I got playing in Texas,” commented Hazzard. Speaking to why being in Texas allowed him to increase his competition, Hazzard stated that it was two factors that made the difference: “one the talent level in Texas is far above the talent level in Connecticut and the other thing is that you are able to play more games. So it’s both, you are playing against better talent and you are playing more often.”

When Hazzard first began high school, despite being accepted to Jesuit as a freshman, he chose to attend Shepton High School, not wanting to leave his friends. Though, Hazzard made his decision under the assumption that he would be able to play on Plano Senior’s varsity baseball team. “I just assumed that, because I was good enough, they would let me play on Plano Senior High’s baseball team, and I would be able to tryout. And … the head coach of Plano Senior, when I went to talk to him during the year, said that it was not possible. I couldn’t play varsity until I was actually at Plano Senior High,” Hazzard recounted.

The news about not being able to play on the Plano Senior varsity squad left Hazzard in dismay. Hazzard believed that, for him to have a solid chance at playing Division 1 baseball, he would need to play on the varsity squad from at least his sophomore year, the year a player is seriously looked at by college scouts, which would hopefully lead to him to be offered a scholarship his junior year, the year most Division 1 committees commit to a school. “I couldn’t afford to wait around until my junior year to start playing varsity baseball,” said Hazzard, because “you are behind the eight-ball then.”

While facing the decision of what next step he would need to take to preserve his dream of playing college baseball, Hazzard was simultaneously being nudged by his parents to attend Jesuit. “My parents kept trying to get me to go to Jesuit and I kept fighting it, because you know [I thought of myself as a] dumb public school kid and I wanted to stay with all my public school friends.” However, having the strong desire to play varsity baseball and continue chasing his dream and his parents pushing him towards Jesuit, Hazzard eventually “decided to transfer in, in January.”

Hazzard’s move to Jesuit would prove to be pivotal, just as his move to Texas did, in not only his baseball career, but in his development of character. Although, the transition from Shepton to Jesuit mid-year would not be seamless for the fourteen year old. “It was crazy, because here I am, behind all these kids that have already started. I transfer in, in January. I go right to playing on the freshman basketball team and I sparingly make it to baseball tryouts, because we were still playing freshman basketball. And I end up making the team, which I thought I had a good chance of doing.”

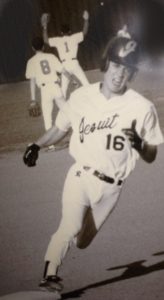

Hazzard, however nervous, was able to make it through the hectic schedule, though he was not so sure about his next challenge. In his first game as a freshman, Hazzard would be facing off against Duncanville, the number one team in the state and the number five team in the nation, which also boasted a future second round pick and big leaguer, Todd Richie, as well as “three or four guys [that would eventually make] it as high as Triple A.” How is that for baptism by fire? “I was like holy cow; I have to face this guy as a freshman,” commented Hazzard. But the instead of running from the moment, like most would, he embraced it, like the future star he would become. “It was awesome; it was great. I couldn’t believe Coach Gruden stuck me in right away.” Hazzard would go on to have a decent game in a loss to Duncanville, but the trial was not over. “Then the next game we played Berkner, I think the very next day we played a double header and I just had two great games. Then I was like okay, I belong. I got past the jitters of the first game and then I was off and rolling from there.”

Hazzard, however nervous, was able to make it through the hectic schedule, though he was not so sure about his next challenge. In his first game as a freshman, Hazzard would be facing off against Duncanville, the number one team in the state and the number five team in the nation, which also boasted a future second round pick and big leaguer, Todd Richie, as well as “three or four guys [that would eventually make] it as high as Triple A.” How is that for baptism by fire? “I was like holy cow; I have to face this guy as a freshman,” commented Hazzard. But the instead of running from the moment, like most would, he embraced it, like the future star he would become. “It was awesome; it was great. I couldn’t believe Coach Gruden stuck me in right away.” Hazzard would go on to have a decent game in a loss to Duncanville, but the trial was not over. “Then the next game we played Berkner, I think the very next day we played a double header and I just had two great games. Then I was like okay, I belong. I got past the jitters of the first game and then I was off and rolling from there.”

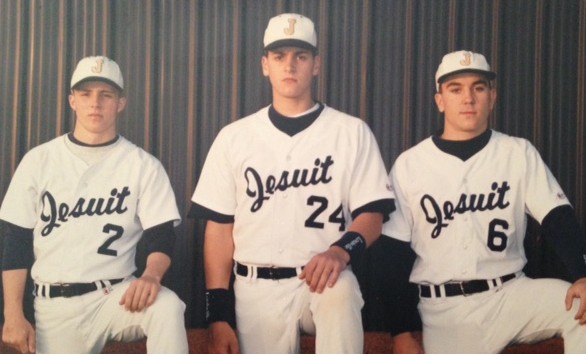

Luckily, Hazzard would not have to face the hardships of being a freshman on varsity alone. “I was fortunate enough [to have] another freshman who played with me on varsity.” That fellow freshman’s name was Jimmy Archie ’93, a member of the Jesuit Sports Hall of Fame as well. Hazzard and Archie would stick together throughout their time at Jesuit, especially during their freshman year. The two teammates would not leave each other’s side. With Archie playing second base and Hazzard playing first, they always had each other’s back. Hazzard commented, “I just can’t think of somebody that I am closer with. Imagine all the times we spent together, me and him, playing right next to each other for four years.” Along with having a teammate to call a friend, having senior leadership would also prove to be a major element of success for Hazzard. “We had a junior and a senior, Ruben Hernandez was a senior, a pitcher who took me under his wing and showed me around and same with catcher David Banmiller, who was a junior. Those two guys were the leaders of the club. They really looked after Jimmy and me as freshman. They knew that we were pretty good and they didn’t want anybody pranking us or making us feel bad for being on the club. They were just to guys that we really looked up to. [They] really set the tone for the rest of our career there, how to conduct ourselves, what to expect, how to go about practice, what coach Gruden was expecting, and how to play the games.”

While Hazzard’s experience of being a freshman on the Jesuit varsity baseball team would be unforgettable, the team’s record during his first two seasons would be. The team was “average” Hazzard’s first season. In spite of, only losing 5 – 2 to Duncanville in a “pretty good game,” considering the circumstances, the varsity squad could not muster the strength finish out games throughout the season. “We played well against a bunch of teams, but not good enough to win,” said Hazzard. Hazzard’s sophomore season would prove to be a “letdown season for us.” The team had high hopes for the 1991 season, but due to players “not buying in,” those hopes were soon dashed. Although Hazzard was not able to will his team to victory over the obstacles, he was able to take on another role, a role every champion takes on at some point, the role of a leader. “That was David’s senior year and he got frustrated a little bit. It was kind of funny, [because] he mentored me as a freshman; then my sophomore year … I had to help him … It was his senior year and he had high expectations, so it was tough.”

While Hazzard’s experience of being a freshman on the Jesuit varsity baseball team would be unforgettable, the team’s record during his first two seasons would be. The team was “average” Hazzard’s first season. In spite of, only losing 5 – 2 to Duncanville in a “pretty good game,” considering the circumstances, the varsity squad could not muster the strength finish out games throughout the season. “We played well against a bunch of teams, but not good enough to win,” said Hazzard. Hazzard’s sophomore season would prove to be a “letdown season for us.” The team had high hopes for the 1991 season, but due to players “not buying in,” those hopes were soon dashed. Although Hazzard was not able to will his team to victory over the obstacles, he was able to take on another role, a role every champion takes on at some point, the role of a leader. “That was David’s senior year and he got frustrated a little bit. It was kind of funny, [because] he mentored me as a freshman; then my sophomore year … I had to help him … It was his senior year and he had high expectations, so it was tough.”

Fortunately for Hazzard, there was a turn in the tide for the Rangers. During Hazzard junior season the team was able to make necessary adjustments and put together a quality season; but it would be Hazzard’s senior campaign that would stand as noteworthy. His senior season Hazzard was named to the Dallas Morning News All-Area Team, something no other player from a private high school had done since Mike Grimes in the mid 80’s, as well as being named most valuable player for the Haltom Tournament. The Jesuit varsity would also make it all the way to the TCIL State Championship that year. Jesuit Dallas faced off against Jesuit Strake, a familiar foe for the Rangers. “We lost to Houston Strake Jesuit every single year and it was because of one pitcher, his name was Byron Tribe. Every year we faced him. He threw like 94 – 95 miles per hour and we could beat everybody but that guy.” The Rangers lost to Starke again that year in the state finals, but it would be Hazard that got the last laugh. “I got revenge on him,” said Hazzard. “In 96, [Byron Tribe] was playing for Alabama and I was playing for the University of Florida. We were playing in the SEC championship game and I hit a three run homer off of him. And as I was coming around third, I said “that’s for high school” and he started laughing.”

For Hazzard, many of the memories made during his time at Jesuit took place on the baseball field, but what seems to have affected him most is the not his experience playing for the Rangers, but Jesuit philosophy. “Jesuit’s motto, Men for Others, is something I live my life by,” commented Hazzard. The most impactful aspect of his Jesuit education would be his time spent at his senior service, Bryan’s House, a center for children born with HIV. “It was hard,” Hazzard said. “For that year [I] was working with kids, and … at the time I was working, we didn’t have a kid live past eleven years old and that is something that is really difficult. You are working with kids and by the end of the year there were a few kids that had passed away. Just seeing that, dealing with that, as a senior in high school, is an eye-opening experience and you start thinking about … these kids. Forget about college, these kids are not even going to have the opportunity to play high school baseball. They might not even get the chance to go to high school.”

Due to his experiences at Jesuit and at Bryan’s House, Hazzard was able to reflect on his own life and what he could do with his talents going forward to assist in whatever way he could. “Look at all the things I have been given, look at all the opportunities I have had, [those] kids would die for that chance. I always thought about that. I always thought about whatever it was, if there were kids around I was going to do everything I can to give my time that I have to be with them and help them and talk about their dreams and aspirations and anything I could do to help make that happen. Jesuit had a huge impact on my life that way. If I was at any other school I wouldn’t have done that; I wouldn’t have been forced to do that. I always credit Jesuit as making me the person I am today.” The effect that Hazzard’s service had on him was so profound, the hunger to aid his community, wherever and however that may be, caused him to take on a series of volunteer positions during his professional career. The first volunteer position Hazzard held was as a head coach for the Dallas Mustangs club baseball fifteen and sixteen year old team. Soon after, Hazzard would go on to be a volunteer coach at UNLV. Not only did Hazzard give his time selflessly to the UNVL baseball team as a coach, but as a community service organizer as well, arranging service opportunities for the players, providing them with the opportunity to give back to their community and teaching them the importance of service. Hazzard’s Jesuit education proved to not only alter his life, but the lives of many others.

As the saying goes, “all good things must come to an end.” Hazzard would graduate from Jesuit in 1993. Fortunately for Hazzard, a new and greater chapter of his baseball story was about to begin. Hazzard was recruited to play baseball as a collegiate athlete at numerous Division 1 schools, but when it came time to realize his dream and sign to play Division 1 college baseball only one place felt right, the University of Florida.

Despite playing first base at Jesuit, Hazzard was recruited to be catcher at Florida. But his position change would not be the biggest challenge he would face during his transition into college baseball; Hazzard felt that distinction would go to his need to bulk up from his “gangly,” 6’3’’, 185 pound stature. “If you look at Derik Jeter, he is 6’3’’, 205 and he looks skinny,” commented Hazzard. “I was a 6’3’’, 185, so … he had me by 20 pounds. I was a stick figure.” However skinny Hazzard might have been, that certainly did not stop hit from tear the cover off the baseball in fall training and inter – squad games. “I came in and … I lead the team in batting average, I lead the team in RBIs, and I was second on the team in home runs after fall inter-squads were done. So I was like ‘Man, I’m doing really well.’ I had some hiccups behind the plate, but I was sparingly playing behind the plate.” Hazzard went on to be named as the Designated Hitter for the rest of the preseason leading up to winter break. But regardless of his success, Hazzard returned from Christmas break to find himself in the bullpen as a catcher for the remainder of the preseason.

Then, just as the season was fixing to begin, Hazzard received a request from his head coach, Joe Arnold, the coach who recruited Hazzard in high school, to meet with him. “He called me in and he said ‘Chuck you tore it up in the fall. We are really happy about everything, but I only see you getting about 100 at bats and I think that is a waste of your talent. We have got a junior and a senior ahead of you at your position. I want to go ahead and red shirt you. I want you to gain about 20 pounds and then come back and win the starting job next year.’” The news was similar to that of which he received from Plano Senior’s head coach and it was just as hard to hear. “I was devastated. I was like ‘Man, I have got to sit out this whole season? What was I going to do?”” said Hazzard. But just as it had before, things worked out for Hazzard. “But honestly that was the best thing for me. It absolutely was. I got all the way up to 205 lbs. by the end of the summer [and] by the start of that next year I was up to 210 lbs.”

Things appeared to be going Hazzard’s way going into his next season at the University of Florida, at least until head coach Joe Arnold was fire and a new coach by the name of Andy Lopez from Pepperdine was hired. Andy Lopez, now the one of the highest regarded coaches in college baseball, came on strong during his first meeting with his new team, not menacing words or sugar-coating anything. Hazzard recounted, “I will ever forget this as long as I live forget this as long as I live: It was our first meeting with Andy Lopez. We were in the locker room, the whole team. He comes in and he says ‘Guys, I’m Andy Lopez, your new head coach. I came over here from Pepperdine. This is Gary Henderson, your pitching coach. This is Steve Kling, your hitting coach. This is Rick Eckstein, your volunteer coach. I need every one of you to do me a favor right now. I want you to look to look at the guy to your right; now look at the guy to your left. That guy is not going to be here next year. Good luck to you.’ Then he walked out.” A lot can be said about Lopez, from him never ceasing to bring a recruiting class to a College World series to his abrasive demeanor, but one thing above all can be remains apparent: He knows how to make an impression.

Hazzard and his teammates felt that same impression after Lopez first meet with the team. “I was like ‘holy cow.’ It was a wakeup call. ‘I better get after it.’ Sure enough, I cracked the starting lineup. I worked hard and I got in people’s faces that were not doing the right thing. I did everything I could to try to help that team win.” Hazzard’s hard work did not go unnoticed, going on to be named a First Team All-American Freshman that year. In spite of a stellar freshman season, Hazzard still worried about whether or not he would be a Gator next year, going into post season meetings with Lopez. “It was funny, after the season was over … you sign up for postseason meetings with the head coach. You get a 15 minute time. He meets with everybody … I was on the second day and he had already let go 15 – 16 guys on the first day. I was like ‘Oh my God, he really is getting rid of everybody.’ So I came into my meeting … I was a Freshman All American that year. I had a really good year, being a Freshman All American. I came into my meeting and I sit down. He says, ‘Chuck …. You were a redshirt freshman last year, so I had no idea what type of player you were. You came in … You are exactly the type of guy we want here. I gave away your scholarship, but stay with me. I will try to get it back. We really appreciate you being here.’” Having his scholarship taken away, Hazzard was now a “free agent.” He quickly began to receive calls from top tier college baseball programs from around the country, from the likes of Oklahoma State, North Carolina, Florida State, Tennessee, and many others, offering with a full scholarship to transfer to their school. Luckily, Hazzard would not need to pursuit any of those offers, because “true to his word, two weeks later Lopez called me back with a bigger scholarship. I resigned at Florida and the rest is history,” as Hazzard says.

Hazzard and his teammates felt that same impression after Lopez first meet with the team. “I was like ‘holy cow.’ It was a wakeup call. ‘I better get after it.’ Sure enough, I cracked the starting lineup. I worked hard and I got in people’s faces that were not doing the right thing. I did everything I could to try to help that team win.” Hazzard’s hard work did not go unnoticed, going on to be named a First Team All-American Freshman that year. In spite of a stellar freshman season, Hazzard still worried about whether or not he would be a Gator next year, going into post season meetings with Lopez. “It was funny, after the season was over … you sign up for postseason meetings with the head coach. You get a 15 minute time. He meets with everybody … I was on the second day and he had already let go 15 – 16 guys on the first day. I was like ‘Oh my God, he really is getting rid of everybody.’ So I came into my meeting … I was a Freshman All American that year. I had a really good year, being a Freshman All American. I came into my meeting and I sit down. He says, ‘Chuck …. You were a redshirt freshman last year, so I had no idea what type of player you were. You came in … You are exactly the type of guy we want here. I gave away your scholarship, but stay with me. I will try to get it back. We really appreciate you being here.’” Having his scholarship taken away, Hazzard was now a “free agent.” He quickly began to receive calls from top tier college baseball programs from around the country, from the likes of Oklahoma State, North Carolina, Florida State, Tennessee, and many others, offering with a full scholarship to transfer to their school. Luckily, Hazzard would not need to pursuit any of those offers, because “true to his word, two weeks later Lopez called me back with a bigger scholarship. I resigned at Florida and the rest is history,” as Hazzard says.

Hazzard’s next few years at Florida would be the best of his baseball career, but they certainly would not come easy. When Hazzard comment about his experience play for Lopez, he stated, “He was tough to play for, but he had a reason behind it. The guy is incredible. He has never had a recruiting class not go to Omaha to play in a College World Series. He knows how to teach the game. He has this thing he says: ‘Practices are mine. Games are yours.’ So practices where like a nightmare … On game day he doesn’t say a word … I figured it out my sophomore year. He wants you to be stressed in practice, so that you are absolutely the most relaxed you can be on game day. It’s fun to see on game day. It works. You can’t question it, because he has had so much success.”

Hazzard’s sophomore season at Florida would arguably be the crowning jewel of his baseball tenure. Back playing in the infield and batting second in the order, Hazzard maintain a .366 batting average, hit 18 home runs (twice that of the second place home run leader for the team, future MLB World Series MVP David Eckstein), and had 67 RBIs. When asked by his sophomore season, Hazzard simply stated, “I went on a run.” That is an understatement. Hazzard went on to be named to the All-SEC Team Regular Season, All-Tournament Team for the SEC Tournament, All-Tournament Team for the NCAA Regional, and then the All-Tournament Team for the College World Series, all while making a College World Series run, something no other player in the history of the University of Florida has ever accomplished. When asked to elaborate on his unprecedented season, Hazzard, remaining humble, commented, “It was awesome. It was very validating … Steve Kling, who was my hitting coach worked really hard with me on going the other way … I was always a pull hitter. [Coach Kling] showed me scouting reports from other teams, [which said] just throw soft away and I would roll it over to the short stop. So we worked on really driving the ball the other way for that season. And 11 of my 18 home runs were to the opposite field. That really paid off. I owe a lot to Steve.”

During Hazzard’s junior season, the Gators and he would not have the same pop they had the previous year. “My junior year was tough because we lost some hitters around me. So I got pitched around a lot. I had pretty much average year at the plate. I played really well defensively.” While the team fought hard to get back to Omaha, the Gators lost to the University of Miami in the Regional Finals.

Going into his senior year, Florida’s prospects looked favorable for returning to the College World Series and Hazzard was excited for the season to begin. Unfortunately, Hazzard was thrown a curve ball. “Then my senior year, in a scrimmaging before the season started, I called for [throw back to first, to tag the runner] and our back-up third baseman slid back feet first, right into my glove, and snapped my thumb.” Not only did the injury look like it was going to bench Hazzard for a good part of the season, but because of him red-shirting his freshman year, he would not be able to apply for a medical red shirt. This meant he would have to sit out for the majority of his senior season at the University of Florida.

Hazzard missed all of February with his injury to his left thumb, “the thumb you drive into the zone with.” Desperately wanting to get return, Hazzard came back in March, but quickly returned to the bench, not being able to effectively swing the bat. “I was flat awful trying to swing the bat. I felt bad. After two weeks I even told Coach ‘I don’t think I’m ready to play.’ So he went back to the freshman, Jason Dill, who absolutely tore it up. It is like one of those tales: Don’t take a day off, because your replacement might go off. Well this kid went off,” said Hazzard. As a freshman, Dill was hitting .368 and had 20 home runs. Seeing the positive effect Dill had on the team, Hazzard “sat back” and did what he could to help the young freshman progress.

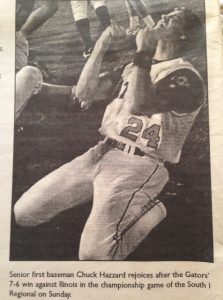

Then, in the Regional Final, came the time for Hazzard to set up. In 1998, the Regional Finals for the NCCA Baseball Tournament were being held at Florida. In what would be Hazzard’s last game on the University of Florida’s campus the unbelievable happened. Jason Dill, the freshman who took Hazzard’s place, in his first at bat “struck out looking, yelled an obscenity at the umpire, and threw his bat half way up the backstop,” recalls Hazzard. “I was like, ‘Wow. What are you doing?’” Hazzard continued. Dill was immediately ejected and the moment came for Hazzard to take his place. “So in the first inning I go in for him to play first base and I get to play my final game at the University of Florida, which meant a ton to me. It was amazing. I played great. I went 3 for 6. The game went into extra innings. I actually saved the game twice. Our short stop, Ty Martin, at the time, with the bases loaded, in the 10th, in a tie ball game, threw one in the dirt that I picked. Then with runners on second and third, in the 12th, he threw one high up the line; I cough it and tagged the guy out as he was trying to dive by me. Both of those would have scored runs, if had not made those plays. Then we end up winning the game in extra innings. It was the greatest thing. We dog pile and everyone is going crazy, because we are going to Omaha, the World Series,” to hear Hazzard tell it. Hazzard experienced what a senior, in his final game, could have only dreamed of and could have easily ended there, but the night was not yet over. “I come down and get interviewed by the local media in the dugout. Everybody has left. The media is interviewing me. It is probably 45 minutes after the game is over. I walk out of the dugout and all 5,000 [fans] were still there and gave me a standing ovation. Then I walked off the field … It is something I will never forget. Just the appreciation they had for me was … it was special.”

Florida went on to the College World Series and lost, despite scoring 12 runs in the first game and 14 runs in the second. “We just had absolutely no pitching,” commented Hazzard. “You would think [if] you score that many runs you should win, but our pitching could not throw the ball down in the zone.” It was not meant to be for Hazzard and the Gators. Though, I am sure, for Hazzard, all the memories and that last night in Gainesville was a fine consolation prize.

After his spectacular sophomore year at Florida, Hazzard was drafted by the Yankees in the 18th round. Wanting to finish what he had started at Florida and get his degree, Hazzard turned down the Yankees. Now entering into his professional career, after not playing for the majority of the season, being of an advanced age compared to most other prospects, and having an injured thumb, Hazzard’s chances of playing professional baseball where less than optimistic. Yet, Hazzard once again persevered and signed as a free agent with none other than the New York Yankees.

Hazzard soon left for Tampa Bay to play Rookie Ball with the Yankee squad. After two weeks of games and practices, Hazzard was told by the organization that, due to his age and the fact that the Yankees had another player in mind for his position, he would be cut from the team. “But they were going to try to get me on another A – ball club. I told them that that was alright,” said Hazzard. Believe it or not, Hazzard was perfectly fine with going back to finish school and finding a typical job. “I wanted to finish school; it was important to me. I didn’t have any delusions of grandeur. I knew I was a pretty good college player, but I wasn’t big enough and at the time … [As everyone knows,] in the 90’s and the early 2000’s, everybody was taking performance enhancing drugs and guys were huge. It just wasn’t for me.”

After graduating from the University of Florida, Hazzard soon found a position as a support representative for a telecommunications software company, but unfortunately it did not last for long. “I didn’t have any plans; I just wanted to see where things took me. I got a really good job out of college … We were doing some really good things. But just the way the telecommunications market went the company, my third year there, started to go downhill,” commented Hazzard. He soon found a new job as a salesman at a company by the name of Stylist Wear. In spite of performing very well at Stylist Wear, Hazzard was left unsatisfied. “I started to question myself. ‘Do I really want to do this the rest of my life?’ Obviously, I couldn’t honestly answer that question. So I ended up leaving and looking for a coaching job. Within a month a [was] offered [a volunteer coaching position] at UNLV, which was great. I came out to [Las Vegas] and the rest is history,” said Hazzard.

Once Hazzard arrived in Vegas, he got write to work with the team, teaching the players all the knowledge he had absorbed through the years. While Hazzard greatly enjoyed his work with the baseball team at UNLV, being volunteer coach is a selfless profession, a life with little comforts besides the game he loved. “When you are a volunteer coach that is exactly what it is. You work full time for no pay. You basically scrape by, by giving lesson and work camps. Try to find ways to scrape by and then coach.” Coaching was great, for Hazzard, was; he was able to teach the game he loved, as well as show his players the importance of service, and that was more than enough for him. “I tell people this all the time. There is nothing in the world like showing somebody [how] to do something and seeing them do it and be successful. The feeling you get from that is … you can’t buy it. You can’t put a price on it. It is awesome. It is so much fun. Because I know the feeling [of succeeding]; I have played it; I have been there. I know what it feels like to be successful. So with my experience, [to be able to] really break it down and work with somebody and see them do something that you taught them is just priceless. It really is.

Hazzard coached at UNLV from 2003 to 2005, when he received an opportunity that was too good to pass up. While at UNLV, Hazzard received a phone call from Steve Rodriguez, the head coach of the University of Pepperdine’s baseball team. Rodriguez played for Andy Lopez, Hazzard’s head coach at Florida, during his time at Pepperdine. Rodriguez would eventually go on to play in the MLB and in the off season train with Lopez’s teams at the University of Florida. Chuck Hazzard happened to be on those same teams and got to know Rodriguez through their training together at Florida. “He called me up, because basically he was running the same program that Andy [did]. He knew I knew the program, so it would be a nice match. He had an opening for a volunteer assistant, so he called me up and asked me to come out there,” Hazzard said. The offer sounded nice to Hazzard, but there was only one problem: It would be hard to make rent in Malibu, California with a volunteer coaching job. “I was [said], “Steve I would love to be in Malibu and Pepperdine, but … I’m scraping by to live in Vegas. How am I supposed to make a living in Malibu, California for crying out loud? How am I going to make it?’ He was [responded], “Well I will figure something out. But would it sweeten the deal if I could make you a graduate assistant and we will pay for a masters degree if you can get in?” That was all Hazzard needed to hear. He was soon accepted into the business masters program at Pepperdine and left for Malibu.

Interestingly enough, though Hazzard went to Pepperdine for the baseball program, it would be his experiences in the classroom that he would value most. “Pepperdine is so amazing,” stated Hazzard. What amazed Hazzard most about Pepperdine was its unique approach to teaching. Instead of having the students create the usual masters thesis, Pepperdine has its students conduct a “masters action research project,” where students are asked to “affect some sort of change within [their] working environment” and record and analyze the process.

After spending some time reflecting on the project, Hazzard had his idea. “At the time … when [coaches] would schedule practices or travel or anything, we would type it up on a piece of paper and stick it on a cork board in the locker room. Then when the guys would come in, they would see everything,” reflected Hazzard. It being the technology era, Hazards plan was to integrate social media into the process and make it easier for coaches and players to communicate. “I start asking coaches what they thought and they thought it was a good idea … I went to my professors and said ‘I have an idea for a website to help college coaches and college players share information … I had about a 20 page outline on it. He looked it over and was like, ‘I want you to meet with some people.’ So he sat me down in front of some key business people in the area. We talked about it [and] we put a really good business plan together.” Then something very interesting happened: “I secured a 750,000 dollar investment and started this business. At graduation I launched hazzsports.com, which was a sports social network where you could upload files and share files of players and teams and everything.”

By the time he left Pepperdine, Hazzard had a fully operating business on his hands and the future looked bright. Hazzard moved back to Las Vegas and began to run his company, but that Hazzsports would be short lived. Hazzsports “did pretty well, but two things happened. One, Eteamz [, a similar website,] beat us out. Then Facebook opened up their API (Application Programing Interface) and beat everybody in the social environment,” Hazzard commented. The loss of his first company would be hard for Hazzard to take; luckily he had a new and grander idea in the works. Hazzard came up with the idea for Totalscout.com, a social media website that would allow for college coaches to share scouting reports of other teams. Before Totalscout.com, most coaches typed up their reports in Excel and faxed or emailed them when they were requested; Total scout changed all of that.

Hazzard launched Totalscout.com in 2010 at College Coaches Convention in Dallas and it was well received, being named the number one new product in baseball at the convention. The service was initially offered for free and became a pay for service one year later. When asked about the company’s performance, Hazzard stated that “We did really well.” Tragically, the introduction of the BBCore bats would soon end Totalscout.com’s success.

The BBCore bats where required for use by all college baseball players in the NCAA in 2011. The new bats are made to it more like a wooden bat, decreasing the velocity the ball travels off the barrel of the bat, in an attempt to lessen the risk of injury by being struck by a ball. The new bats did more than just that; they also completely destroyed the need for a service like Totalscout.com. “Now, nobody cares about scouting reports, because you basically pitch all batters the same because there is really no such thing as a power hitter anymore in college baseball. [For] pitchers, you still share reports, but you don’t really go in depth in it. Nobody is willing to pay for scouting reports anymore. [They are] not even really that big of a deal,” stated Hazzard. As one might expect the second decline of one of his companies was hard to take, especially one that seemed to have so much promise. But possessing the hard-nosed, never say die attitude that kept on Florida’s baseball team and lead him to multiple honors, Hazzard pushed on.

“The next year I brought on a friend of mine, whose name was Andrew Bachman,” stated Hazzard. Bachman, an established businessman, who has gone as far as the White House to speak to the young entrepreneurs, was the perfect partner for Hazzard. Hazzard offered Bachman a piece of the company that owned Hazzsports and Totalscout and went to work on creating a new business. “We worked out an idea to start a sports nutritional supplement company. [With him being] a big workout freak [and] me, being in the sports industry for the better part of my life [and having] so many contacts; we figured it would just be the right way to go and the right way to take this company,” said Hazzard. Game Plan Nutrition, Hazzard and Bachman’s company, that works with personal trainers to supply clients with the “all natural … NSF certified” products they need to stay in peak physical shape. Game Plan Nutrition is now a part of a six billion dollar industry that, as Hazzard says, is “really saturated.” The road appears to be long and tough; but knowing of Hazzard and Bachman’s experience and genius, it would be hard to bet against them.

Now here we are, inducting Chuck Hazzard into the Jesuit Sports Hall of Fame. He is a truly amazing man, with a truly amazing story, and certainly worthy of the honor. When asked about what it means to him to be inducted, Hazzard commented, “I always say that Jesuit made me the man I am today and to be associated now forever with the school is an honor hat is beyond me. I love Jesuit. I love the fact that I am going to get to tell people I am a hall of famer. It is awesome.” Hazzard continued, “I though one of my greatest accomplishments was graduating from Jesuit; I really did … It has made me everything I am today; it really has. It was the foundation for my life and to be honored athletically just means the absolute world to me.”