What is the best pitch in baseball?

Baseball has three categories of pitches: fastball, breaking ball, and offspeed.

A fastball is meant to use speed as an advantage and generally does not use deceptive movement. However, there are three types of fastballs: four-seam, two-seam, and cutter. The four-seam is intended to stay straight, and since four seams provide drag, it is good for getting lift and forcing batters to swing under it. The two-seam or sinker is thrown at about the same speed as the four-seam, but with how the seams are aligned and the average arm angle or tilt of the pitcher, it runs to the arm side of the pitcher; righty runs to the right and vice versa. The cutter does the opposite, but since there is a more unnatural way of gripping and throwing it, the cutter generally has less speed and less backspin, maybe even having some drop.

The breaking ball is a much broader category because there are many more ways a ball can spin besides backspin. The goal of a breaking ball is to deceive hitters through topspin, gyroscopic spin, and side spin. Breaking balls are not as fast as fastballs because the person throwing cannot produce the same force as behind the ball, like when throwing a fastball.

The three main types of breaking balls are curveball, slider, and knuckleball. There is technically a slurve ball, which is just the combination of a slider and curve, but it doesn’t count. The curveball has three subcategories: 12-6, which means the topspin is perfectly angled at where the ball is going straight down, with zero horizontal movement:

The next type of curveball spins at the 1-7 to 3-9 axis angle, with more glove-side movement (moves left for a righty). It scares hitters more because it goes at righty hitters and then breaks towards home plate/the strike zone; for example, Clayton Kershaw has a more glove-side moving curveball.

The knuckle or spiked curve generally moves a little less and can be thrown with more intent than others while maintaining control; for example, Gerrit Cole throws a much harder curve, but it has much less movement generally:

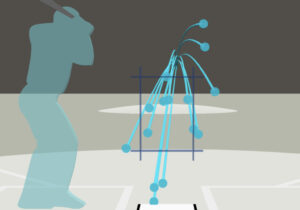

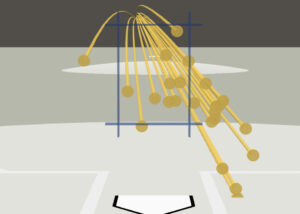

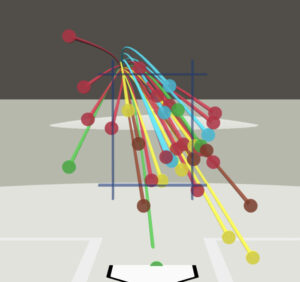

The slider spins gyroscopically, which means the spin axis is angled towards the batter allowing it to be thrown harder because pitchers can stay behind it more. For example, Trevor Bauer throws a slider that moves very far horizontally, it does move vertically, but the main characteristic is its horizontal movement which can get up to 20 inches of induced horizontal break (away from a right handed hitter). The graphic on the right is a Trevor Bauer knuckle curve and on the left a Trevor Bauer slider, both from the same game:

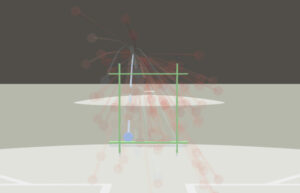

The knuckleball is an odd one out, the goal is to give the ball as little spin as possible to let all the winds in the air take over the ball, and it moves unpredictably. For example, R.A. Dickey is one of, if not the best knuckle baller in the recent generations, even winning a CY Young without throwing a pitch over 85mph. This was due to the sheer unpredictability of his knuckleball, the thing that makes it so effective is that no one knew where it was going, not even R.A. Dickey himself. The lack of spin enabled the little changes in wind and air pressure to take total control of the ball and create a wobble effect in the path to the plate:

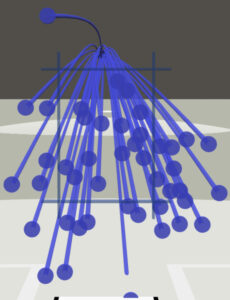

The perspective of a right-handed batter illustrates how all the pitches look the same at the white dots, which represents one-third of the way to the plate. Not even a quarter of a second later the balls are scattered all over the place.

This second graphic just shows the chaos and unpredictability of the pitch, these are also the same pitches shown in the first graphic.

The goal of the offspeed is to look like a fastball and use its movement and speed change to deceive hitters. There are only two types of offspeeds: The change-up and the splitter. The change-up looks like a fastball but is usually 8 to 12 mph slower than the pitcher’s fastball. The two types of change-ups are four seam and two seam; in this case, the two-seam changeup is much more common. Four-seam change-ups are rare because they have backspins and are slower than a fastball, so they are just slow four-seam. The two-seam/sinking change-up is much better because the pitcher can generate sidespin due to the drop in velocity and how the pitcher can get on the side of the ball, not just behind it. The splitter is thrown with fingers on the outside of the ball and produces as little spin as possible, nowhere near as little as the knuckleball, but it still creates a somewhat unpredictable drop.

There are three ways to judge the best pitch: The first way is by how good the pitch is by itself, meaning that if the batter knew the pitch was coming. One example is Nolan Ryan’s fastball because of how overpowering and fast it was or R. A. Dickey’s knuckleball because hitters struggled when they knew it was coming due to the unpredictability. The second way to classify the best pitch is overall performance; this year, Shohei Otani’s slider or Jacob Degrom’s slider and fastballs are good examples. The third way is to judge the pitch independently of the pitcher, for example, the sinker or the cutter.

When the batter knows what is coming, the best pitch by itself has to either be incredibly overpowering or have some unpredictability. For this year, I will use Aroldis Chapman’s fastball: Overall, he throws his fastball 65% percent of the time (this year (2023 season, not including playoffs or World Series), which is rather high, but when he gets behind in counts, it shoots up to 85-90%. The main characteristic of his fastball that makes it so effective is both the 99 percentile speed (99.5 mph avg) and the 17 avg arm side run of his fastball. Another underrated stat on what makes his fastball overpowering is his extension, for example, Aroldis Chapman releases the ball 7.5 feet in front of the rubber, so the baseball only travels about 53 feet, and the average extension is 5.5 feet, so Chapman gains an extra 3 mph of “perceived velocity.” Hey Tom House, what is perceived velocity?

“Perceived velocity is how fast the pitch appears to the hitter. It factors in the velocity of the pitch and the release point of the pitcher. We know that every one foot of distance is three miles per hour to the batter’s eye. So the longer a pitcher strides, and the closer his release point is to home plate, the faster the pitch will appear to the hitter. Any hitter will tell you there are certain pitchers they face whose pitches just tend to ‘get on them faster.’

Take Chapman, who strides about as long as anyone in baseball; while the average pitcher strides an average of 87% of his height, Chapman’s stride is seven and a half feet, or 120% of his 6-4 body. When he throws 100 miles per hour with a release point that is 52.5 feet from home plate, the pitch will appear 4.5 miles an hour faster than that of a pitcher striding six feet and throwing 100 miles per hour whose release point is 54 feet from home plate. And while 100 miles per hour is pretty scary, 104.5 is even more terrifying.”

– Tom House (Nolan Ryan’s pitching coach and Tom Brady’s QB / Throwing coach)

Thanks, let’s focus on the second way to characterize the best pitch, overall performance, for this year I am going to choose Gerrit Cole’s fastball AND slider, this is because of each pitch’s respective run prevention value, which is 100% for the fastball and 96% for the slider.

First, these two pitches almost alone, drove Gerrit Cole to his first ever Cy Young, throwing them 74% of the time, more than 50% fastballs, and about 20% slider, with the fastball sitting at 97 mph average and touching 101 mph, while the sliders sit around 89 mph. The main thing that makes these pitches so effective is their ability to tunnel and deceive hitters (which is something I discussed at the beginning).

The impressive velocity, efficiency of innings, and ability to tunnel, paired with his very advanced ability to “lock-in,” means when he is in a run-vulnerable state (like bases loaded or runners on second/third, he is able to do better, throw hard, and increase control), which enabled him to match/get close to career-best numbers like ERA, which was 2.63; the amount of innings, which was 209, putting him near the top of the MLB in 2023, especially impressive for his age 32 seasons; and lead the struggling Yankees to a fifteen and four record in the games he pitched, which is quite impressive for an eighty-two and eighty season, roughly a 51% win average (for the Yankees).

The third way of measuring the best pitch in baseball is to look at a single subcategory of pitch (2 seam fb, curve, slider, etc.), and its performance throughout the 2023 season. This way of characterizing the best pitch is important because it is the most directly related to the phrase “best pitch”. After all, it is the performance of that exact pitch.

Max Scherzer throws all of the six main pitches (fb, sl, cu, ch, ct, si):

The 2023 season has seen the slider emerge as the undisputed king among pitches. A thorough examination of the statistical landscape reveals its dominance in multiple facets of the game.

The impact of the slider on strikeouts during the 2023 season is particularly noteworthy. Pitchers who featured a top-tier slider consistently ranked at the top of the league in strikeouts per nine innings (K/9). The average K/9 for these pitchers surpassed 10, emphasizing the slider’s effectiveness in generating swings and misses. The pitch’s late break and deceptive movement have proven to be a lethal combination, leaving batters flailing and contributing significantly to elevated strikeout rates.

Crucially, the slider’s prowess extends to high-leverage situations. In clutch moments where the outcome of the game hangs in the balance, pitchers relying on the slider have excelled. Opponents’ batting averages against sliders in high-leverage situations remained markedly lower than those against other pitches. This statistical evidence underscores the slider’s reliability and effectiveness under pressure.

Versatility is another key aspect where the slider shines brightly. Analyzing its success against both left-handed and right-handed hitters during the 2023 season reveals its well-rounded nature. The batting average against sliders from left-handed batters and right-handed batters consistently remained below the overall league average, demonstrating the pitch’s capacity to neutralize hitters from both sides of the plate.

When it comes to run prevention, the slider continues to stand out. Pitchers heavily incorporating the slider into their repertoire in 2023 consistently boasted lower earned run averages (ERAs) compared to those relying on alternative pitches. The ability of the slider to induce weak contact and generate ground balls translated into tangible results, contributing to lower run-scoring outcomes for pitchers who favored this formidable pitch.

In summary, the 2023 MLB season has firmly established the slider as the preeminent single pitch in baseball. From its ability to amass strikeouts and excel in high-pressure situations to its versatility against hitters from both sides of the plate, the slider’s statistical dominance reinforces its status as a game – changing force on the diamond. As the season unfolds and strategies evolve, the slider’s numerical supremacy positions it as the pinnacle of single pitches in modern baseball.

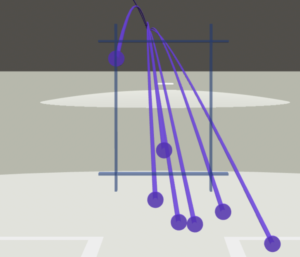

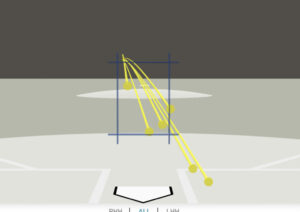

Max Scherzer’s sliders from game 3 of World Series:

To conclude, among the multiple types of pitches and the scenarios which they may shine, there are a few pitches in these categories that shine the brightest. First, in the category of the best pitch, just generally, is the undisputed king of baseball: the fastball, a pitch that was the only pitch thrown for the first 200 years of the game and the staple pitch of pitching. Second, directly based on the recent performance and specific to the pitcher, as I previously mentioned, is Gerrit Cole’s fastball; the reason I highlight his fastball is that it is far more of a stand-out pitch than his slider, even though both are great. Finally, the pitch’s success not related to the pitcher, this ends up being the slider, due to the recent mastery of it, especially in 2023 where a lot of pitches threw it with a higher frequency than their fastballs.

Dillon Brandt 25′